How I cut down stakeholder rework with better UX storytelling

I used to leave design presentations with a stack of changes and a heavy heart. Over 20 points to revise was normal. Most of the feedback wasn’t from users; it was subjective opinions from stakeholders. Nothing felt anchored. I’d rush through the screens, hoping the room wouldn’t ask hard questions.

Then I learned to stop just showing screens and start telling the story behind them. The result was immediate: clearer conversations, fewer rounds of rework, faster buy-in, and designs that actually reflected user needs.

In this article, I will share the exact, repeatable approach I use. It’s practical, battle-tested, and built to be used in real stakeholder meetings.

Why feedback spirals out of control

Most stakeholder feedback isn’t malicious; it’s social. People feel the need to contribute in a meeting. A team lead says, “I don’t love these cards,” and others echo them to show alignment. Without structure, one offhand comment becomes a cascade of edits.

When dozens of people have opinions, traditional ad-hoc strategies break down. That’s why structure matters: it transforms disconnected opinions into focused, evidence-backed discussion.

The turning point: A lesson from a senior leader

My wake-up moment was watching a senior design lead present. He didn’t open with a mockup. He walked the room through:

- A short UX audit and competitor review

- Real usability tests and qualitative quotes

- A/B results that proved one direction performed better

His narrative followed a clean arc: Context → Evidence → Insight → Design → Business impact. Because every choice was tied to research, stakeholders stopped debating styles and started discussing trade-offs. They approved a budget for new imagery on the spot.

That structure is what I replicate now.

PS: If you want the theory behind storytelling, the comparison of Hero’s Journey vs Pixar’s story spine is a useful primer.

The framework (and why it works)

I treat every major design presentation like a business case, not a design review.

The structure I use — Context → Evidence → Insight → Design → Business impact — is about “telling a story” and also controlling the narrative arc. By framing design this way, you’re not asking for opinions, you’re guiding executives toward decisions.

Each step answers a leadership-level question:

- Context → “Why should I care?”

- Evidence → “Is this grounded in reality?”

- Insight → “What does this mean for our users and market?”

- Design → “How do we act on it?”

- Business impact → “Why does it matter to revenue, growth, or efficiency?”

Step-by-step walkthrough (read this like a presentation script)

Below is how I presented my design work for Project CH (the case example we will be using in this article).

My intro:

“Before I show the visuals, I want to walk you through what we found in research, what users told us, what that meant, and how that shaped the designs you’ll see.”

Pause 2–3 seconds. Make people look up.

1) CONTEXT — Set the scene (what to say, what to show)

What I said:

“We started this project to solve one clear problem: users land on the homepage and don’t immediately know how to take action or what the platform does. Our objective was to make the platform’s value obvious and guide users to two primary actions: Find work or Hire talent, in as few steps as possible.”

What I showed:

Why:

This frames the audience to judge the design by whether it solves a real user problem and meets the project objectives.

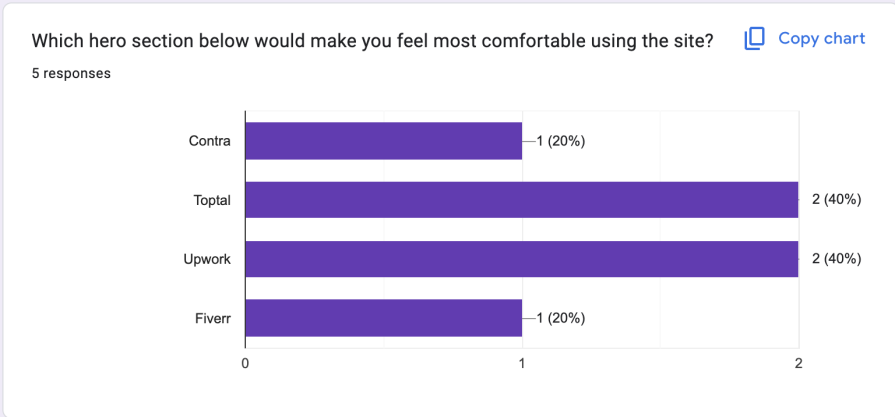

2) EVIDENCE — Don’t tell it, prove it (how to present data)

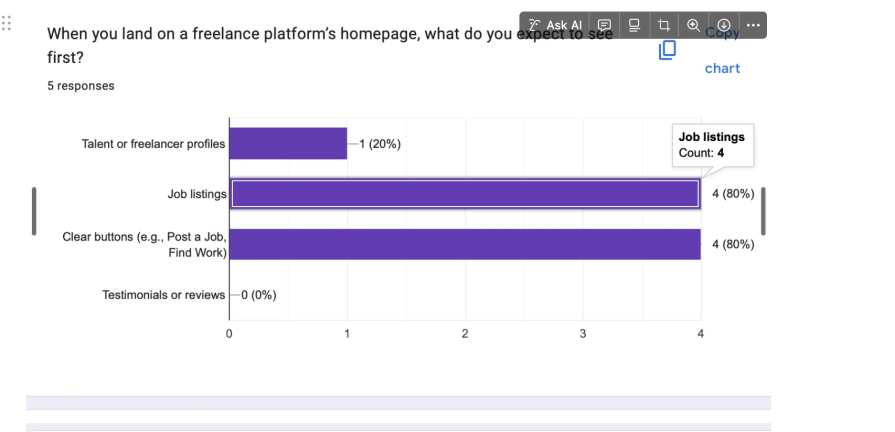

What I said:

“Here’s what users told us when asked: ‘When you land on a freelancer homepage, what do you expect to see first?’”

What I showed:

Why:

Evidence moves the conversation from “I feel” to “users said”:

3) INSIGHT — Translate evidence into meaning

What I said:

“The data tells us users want action first, persuasion second. When a homepage leads with branding or abstract messaging, users hesitate and drop off. They need fast access to listings and clear next steps.”

What I showed:

Why:

This is the connective tissue that makes your design inevitable; it explains why the problem exists and what to change.

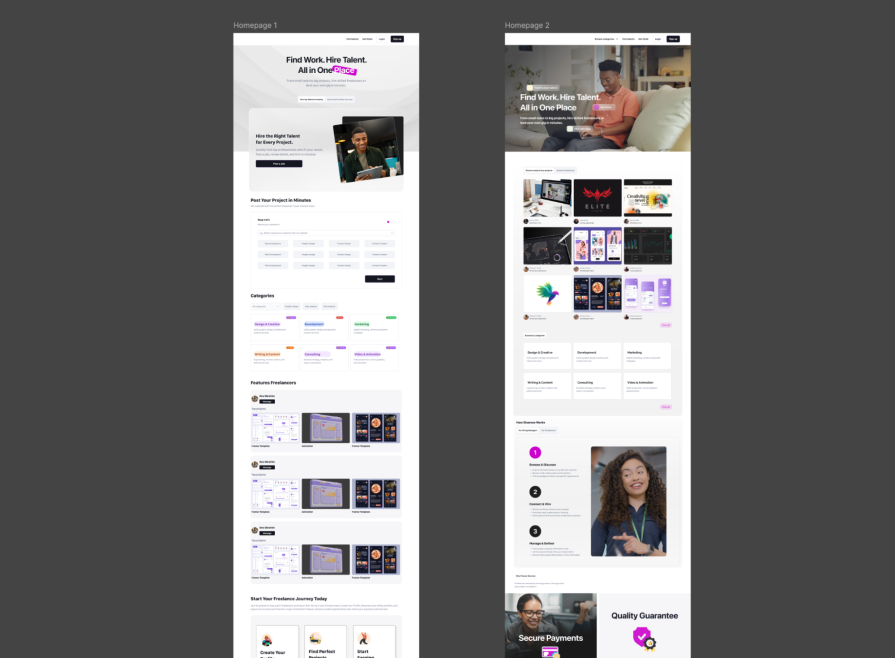

4) DESIGN SOLUTION — Present the design as the answer

What I said:

“We designed two proven directions that respond to this insight.”

Why two, you might ask? Well, the goal was to give stakeholders a sense of control (without losing mine):

- People don’t like to feel boxed in. If you show just one design, they often feel their only power is to accept or reject it

- Presenting multiple design paths isn’t about hedging bets; it’s about designing the decision-making environment. At senior levels, stakeholders are less interested in “which mockup looks better” and more concerned with trade-offs: speed vs. quality, innovation vs. risk, short-term conversion vs. long-term trust

By framing two viable options, you shift the conversation from taste-based critique (“I don’t like this”) to strategic choice (“Do we value faster onboarding or deeper qualification at this stage of growth?”). That reframing elevates the room from surface-level preferences to business alignment.

- Psychologically, it’s harder for someone to reject both designs completely. Most times, they’ll lean toward one, even if they want tweaks

Turns criticism into preference, not dismissal:

- Instead of “I don’t like it,” feedback becomes “I prefer option A over B because…”That “because” gives you insight into their real priorities

We also have the ownership bias — once stakeholders pick one, they start to defend it. It’s no longer your design; it’s their choice. That makes approval smoother.

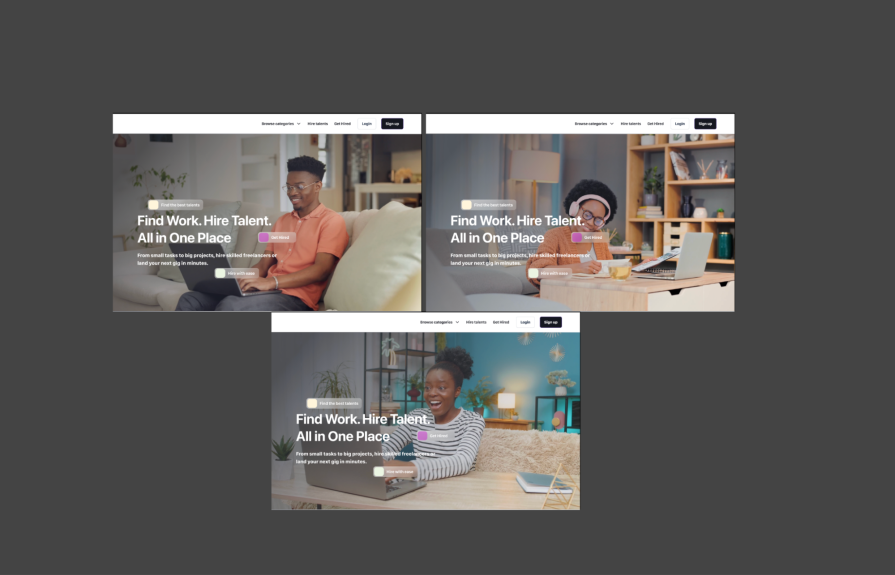

Another interesting aspect of this project I had to defend was the choice of using a video for the hero section instead of a static image:

The idea was simple: we wanted to evoke a feeling, not just show a picture. From the research, we identified our target audience as young, skilled professionals looking for jobs and companies searching for agile talent. When we looked at competitors, we noticed a common pattern: most of them relied on bold, striking imagery to grab attention. It worked, but it only went so far.

Instead of repeating that, we asked ourselves: what if we went beyond an image and created an experience? That’s what led us to the video concept. A still picture can only suggest what the platform does, but a video brings it to life instantly.

In our hero section, we chose to show a freelancer, relaxed at home, smiling while working. It wasn’t just a visual of someone “doing a job.” It was a story of freedom, confidence, and joy, the lifestyle our target users aspire to. So when someone lands on the page, they don’t just see a platform. They feel what it’s like to succeed at it.

The headline: “Find Work. Hire Talent. All in One Place”, made the promise explicit, while the video made it believable.

That was how I positioned and sold the idea of using video in the hero section, not as a design flourish, but as a storytelling device grounded in research and user aspiration.

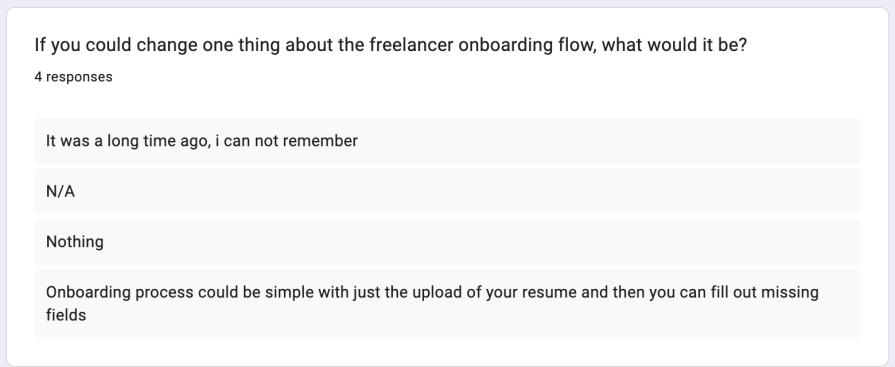

5) BUSINESS IMPACT — Close the loop

What I said:

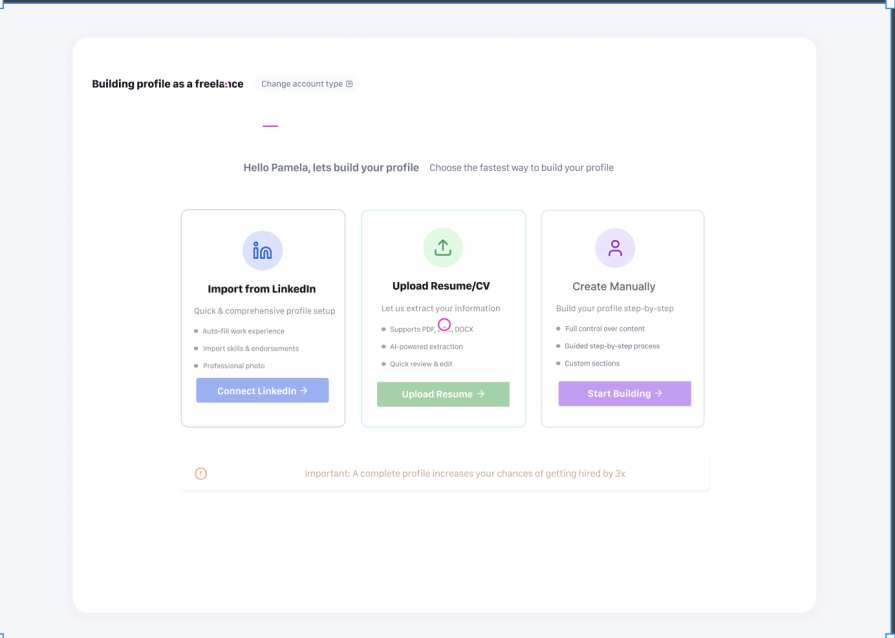

“One of the biggest pieces of feedback we got during research was about the onboarding process. Users felt it was unnecessarily complicated, and many dropped off before even getting a chance to explore the platform. A recurring suggestion from participants was simple: “Why not let me just upload my resume and get started?”

What I showed:

Design I showed afterwards:

So we redesigned the onboarding flow around that. Instead of a long, multi-step form, we introduced a resume upload option and other options that could automatically populate key fields.

What I went on to say:

“This change wasn’t just cosmetic — it addressed a real friction point. By simplifying onboarding, we reduced the cognitive load on new users and made the first step toward finding work or hiring talent effortless.

From a business perspective, this has a clear impact and a business win:

- Fewer drop-offs in onboarding means more users complete registration

- More registrations translate into a larger talent pool for clients and more job opportunities for freelancers

- Ultimately, that means stronger engagement on the platform and higher revenue potential

We also set up tracking for drop-off points across the onboarding funnel. This way, we can measure the difference after launching the new flow. The expectation is straightforward: fix the bottleneck, increase successful signups, and fuel growth across both sides of the marketplace.

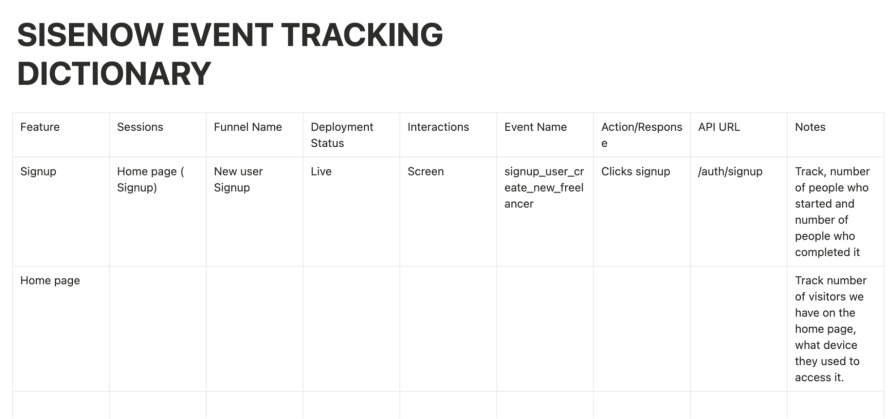

What I also showed:

Exact words to use when stakeholders go subjective

If someone says, for example, “I don’t like the video; it’s too bold.”

Say:

“Thanks, can I check: is that about the tone or are you worried it distracts from the job listings? If it’s about tone, we can try alternative footage; if it’s about distraction, we can test a shorter video. Our priority is to drive first action, which of those concerns would impact that goal most for you?”

If someone starts to argue color or microcopy:

Say:

“Noted. Before we land on button color, can we agree on the priority? Right now we’re focused on first action rate and trust signals. If color is blocking the choice, we can quickly test it, but I’d like us to prioritize the things that move the business metric first.”

Redirecting subjective feedback isn’t about pushing back — it’s about anchoring the room to priorities that everyone already agreed on.

Instead of debating surface-level details, I use a tactic I call metric tethering:

- If a stakeholder questions tone, I tie the discussion back to brand trust scores

- If they challenge visuals, I tie it to conversion or completion rates

- If it’s about copy, I tie it to clarity in the funnel drop-off data

This way, the conversation never slips into personal preference; it always returns to outcomes leadership cares about.

For every section you present, follow this mini-script

- Show the evidence slide (survey or quote) → “This is what users said”

- State the insight (one sentence) → “This told us X about user needs”

- Show the design (option A/B) → “Here’s how we responded”

- Ask for feedback tied to the insight (one question) → “Which option solves the user’s needs better? Why?”

- Capture decision & owner → “If we agree, who owns the action to move it forward? (Design, engineering, content?)”

The role of stakeholders in your story

Let me be clear: stakeholder feedback is not useless. In fact, it’s critical. Stakeholders bring deep knowledge of the business, the market, and the product vision, things that users alone may not reveal. Ignoring them would be a mistake.

The problem is not the feedback itself, but the way the conversation is framed. Without a clear story, their input often drifts into surface-level opinions like “I don’t like this color” or “Can we move this card over here?” That’s when design reviews turn into endless rework.

But when you ground your presentation in context, evidence, insight, and business impact, you give stakeholders something more meaningful to react to. Their feedback shifts from personal preference to strategic alignment. Instead of debating colors, they’ll ask, “Does this solve the onboarding drop-off?” Instead of rejecting a design outright, they’ll discuss trade-offs and priorities.

That’s the role of storytelling. It doesn’t replace stakeholder input; it makes it sharper, more constructive, and aligned with what actually benefits users.

Conclusion

I started this journey dreading stakeholder meetings — my designs always came back with 20+ changes, most of them based on personal taste rather than user needs. But learning UX storytelling shifted everything.

Storytelling in UX isn’t fluff; it’s a form of leadership. When you frame designs through context, evidence, insight, and impact, you stop defending pixels and start steering strategy. That’s the difference between being seen as “the designer in the room” and being trusted as “a product leader who uses design to drive business outcomes.

That’s the power of storytelling. It’s not about sugar-coating your work or speaking in big words. It’s about showing the journey from user problem to business impact in a way people can understand, remember, and rally behind.

So the next time you step into a stakeholder meeting, don’t just show your screens. Tell the story behind them. It’s the difference between design by opinion and design by evidence + and it might just save your sanity.

The post How I cut down stakeholder rework with better UX storytelling appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

This post first appeared on Read More