Visual design’s future is the scenic route

How design will evolve from solving functional problems to creating depth, connection, and significance in the age of AI.

I recently stumbled across a LinkedIn post by Rafael T. making a bold prediction—by 2030, 90% of interfaces will be invisible. According to him, voice, chat, and autonomous agents will replace screens and buttons as the primary ways we interact with technology.

Designers, he argued, will no longer focus on crafting pixels but on choreographing conversations, shaping intent, and defining how AI behaves. His conclusion was stark—visual design, as a distinct profession, will disappear.

This argument isn’t new. In fact, I made a similar prediction nearly two years ago. In December 2023, I published an essay titled Design Is Dead. And We Have Killed It. I explored how AI’s rapid evolution would render design — not just designers — obsolete.

I argued that visual design’s core purpose is to translate complexity into clarity. And if AI can achieve that same clarity by unifying experiences and anticipating needs across contexts — particularly through non-visual interfaces — it will eventually absorb the function of UI design entirely.

But since writing that article, my perspective has been shifting. I now believe that visual design may still have a pulse. Understanding that future starts with a simple metaphor— taking the scenic route.

From utility to choice

When traveling, we often face a choice. The fastest route is efficient and predictable, optimized to get us from point A to point B. The scenic route is slower and longer, but richer — winding roads through forests, detours along a coastline. It doesn’t make “sense” in a strictly utilitarian framework, but it does as an expression of human values.

This metaphor maps directly onto the current debate about design. The rational view assumes that once AI and invisible interfaces handle functional tasks, visual design will become unnecessary. After all, if a voice agent can complete a transaction instantly, why bother designing a screen?

The answer is that necessity and value are not the same thing. While the fastest route may be a straight highway, that doesn’t make it the most meaningful or memorable. In the same way, a frictionless voice interface might be the most efficient way to get something done, but it is not always the most satisfying.

When trying to understand how such value is communicated, semiotics can help explain this process by describing the dualistic nature of interface communication.

Every interface communicates on two levels—the denotative (what it does) and the connotative (what it means). Invisible systems excel at the first. Visible, intentional design emphasizes the second — signaling care, identity, values, and intent. Choosing to design something, even when you don’t need to, declares that the interaction is meant to be experienced, not just completed.

Think of a banking app that still shows you a welcoming dashboard instead of just confirming a deposit by text, or a smart-home system that visualizes energy usage rather than simply optimizing it silently. Both are gestures that transform a transaction into a relationship. They show that interfaces do more than deliver outcomes—they infuse narratives, values, and meaning into those outcomes.

The value of inefficiency

Once utility is taken care of by automation, effort itself becomes expressive. What optimization once treated as waste — time, ornament, friction, even delay — can instead become thoughtful design materials. They slow people down just enough to notice, reflect, or connect.

For users, the “scenic route” means richer, more meaningful interactions. A well-crafted interface invites exploration instead of simple completion, shaping how people feel as they move through a system because it makes the care and effort behind it visible.

We often feel that difference when someone chooses to spend effort on us.

For example, when I left a company after nearly 13 years, my boss and mentor mailed me a handwritten note congratulating me and thanking me for my work and friendship. He could have sent an email — faster, clearer, and certainly more legible (his handwriting is atrocious) — but I would have read it once and moved on. Instead, I keep that note on my shelf as a reminder of the effort and story it represents. The message mattered more because it cost something to create.

This dynamic is well described by signaling theory, which helps explain why effort itself can communicate value. A “costly signal” — one that takes time or effort — carries more weight because it tells users that the experience was worth investing in.

A handwritten note feels meaningful because someone cared enough to write it. And in the same way, a thoughtfully designed product feels intentional because it respects the user’s humanity.

Human variability and the future of design

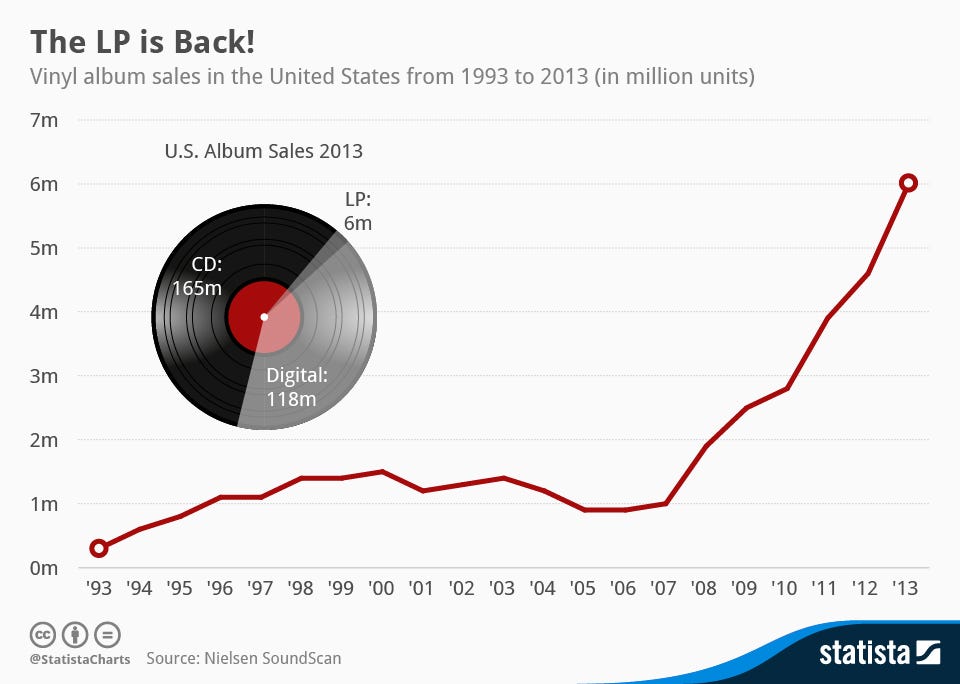

Most people will choose frictionless utility for routine tasks. But smaller groups seeking deeper, more intentional experiences often shape markets and brand perception far beyond their size. Just look at how vinyl records made a comeback. Few would have predicted such a revival in an era dominated by streaming.

What was once considered obsolete can return with renewed relevance when it speaks to deeper values, and design is no different. The rise of AI and agent-based interaction won’t erase visual design—it will reframe it. As everyday interactions shift toward voice and conversation, design’s role will move from functional to expressive.

Designers won’t win by competing with AI on speed and output. Machines will always outperform there. But they cannot replicate human judgment, taste, or the ability to infuse meaning into form. The designer’s work will be knowing when a scenic route is worth taking — when inefficiency signals values or identity.

Visual design will no longer be the default. But precisely because of that, it will become more powerful — shaping meaning in ways automation cannot, long after screens disappear.

Don’t miss out! Join my email list and receive the latest content.

Visual design’s future is the scenic route was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More