How to use the useEffect hook in React: A complete guide

If you’re serious about mastering React in the Hooks era, getting comfortable with useEffect is essential. Unlike the old class-based lifecycle methods (componentDidMount, componentDidUpdate, etc.), useEffect lets you handle side effects directly inside functional components — everything from data fetching to DOM manipulation to setting up subscriptions.

At first, it might feel confusing. Why does it run after render? Why does it re-run on prop changes? What’s with the dependency array?

This guide aims to demystify those questions. I’ll walk you through the core ideas behind useEffect, share lessons from real-world projects, and explore patterns that will help you avoid common pitfalls. You’ll also find example code throughout — pulled straight from a companion GitHub repo:

Editor’s note: This article was updated in June 2025 to add a “When NOT to use useEffect” guide, add more real-world examples, and provide practical steps to use useEffect effectively. The previous update in 2023 added a comparison of the useState and useEffect Hooks and explored the relationship between the useEffect Hook and React Server Components.

TL;DR: How to use useEffect in React

useEffect is a powerful React Hook that lets you run side effects — like fetching data or updating the UI — in response to changes in your component. It helps you manage tasks that happen after the component renders. Here’s a basic example that runs code only once when the component mounts:

useEffect(() => { // Code to run once when component loads }, []);

What is the useEffect hook in React?

What are the effects, really? Examples include fetching data, reading from local storage, and registering and deregistering event listeners.

React’s effects are a completely different animal than the lifecycle methods of class-based components. The abstraction level differs, too. To their credit, lifecycle methods do give components a predictable structure. The code is more explicit in contrast to effects, so developers can directly spot the relevant parts (e.g., componentDidMount) in terms of performing tasks at particular lifecycle phases (e.g., on component unmount).

As we will see later, the useEffect Hook fosters the separation of concerns and reduces code duplication. For example, the official React docs show that you can avoid the duplicated code that results from lifecycle methods with one useEffect statement.

A couple of key points to note before we get started:

- Functions defined in the body of your function component get recreated on every render cycle. This has an impact if you use it inside your effect. There are strategies to cope with it (for example, hoist them outside of the component, define them inside of the effect, use

useCallback) - It is important to understand basic JavaScript concepts such as stale closures; otherwise, you might have trouble tackling problems with outdated props or state values inside of your effect

- You should not ignore suggestions from the React Hooks ESLint plugin

- Do not mimic the lifecycle methods of class-based components. This way of thinking does more harm than good. Instead, think more about data flow and the state associated with effects because you run effects based on state changes across render cycles

Steps to use useEffect effectively

-

Define the effect clearly — Write focused code for the side effect inside the

useEffectcallback -

Control dependencies carefully — List only variables that should trigger the effect when changed

-

Add cleanup logic when needed — Return a function to clean up subscriptions, timers, or listeners

-

Avoid unnecessary effects — Don’t use

useEffectfor tasks better done during rendering -

Keep effects fast and efficient — Avoid heavy work inside effects to maintain performance

How to use useEffect for asynchronous tasks?

In React, useEffect is the standard way to run asynchronous tasks after a component mounts — like fetching data, subscribing to updates, or syncing with external systems.

Take this real-world scenario: You’re building a dashboard that shows the logged-in user’s profile details. You don’t want to block rendering while fetching the data, and you only want the fetch to run once — right after the component loads.

That’s where useEffect shines:

import { useState, useEffect } from "react";

function UserProfile() {

const [profile, setProfile] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

async function fetchProfile() {

try {

const res = await fetch("/api/user");

const data = await res.json();

setProfile(data);

} catch (err) {

console.error("Failed to load profile", err);

}

}

fetchProfile();

}, []);

if (!profile) return <p>Loading...</p>;

return (

<div>

<h2>Welcome, {profile.name}!</h2>

<p>Email: {profile.email}</p>

</div>

);

}

When does useEffect run during the component lifecycle?

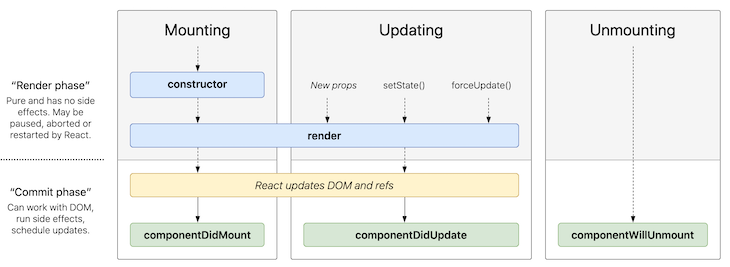

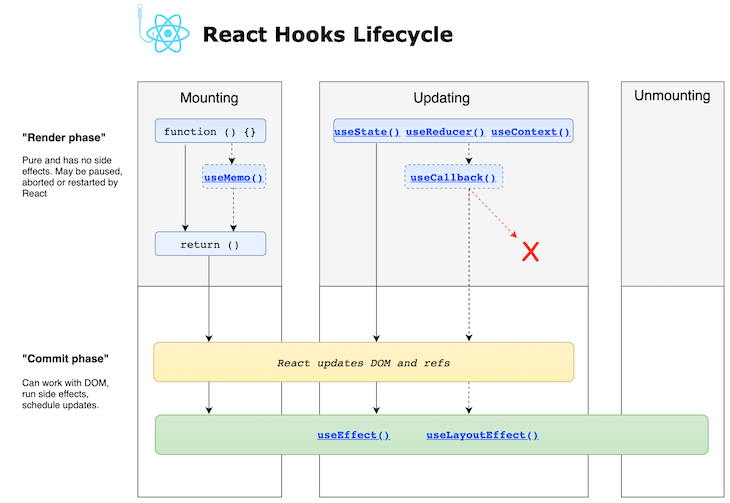

This interactive diagram shows the React phases in which certain lifecycle methods (e.g., componentDidMount) are executed:

In contrast, the next diagram shows how things work in the context of functional components:

This may sound strange initially, but effects defined with useEffect are invoked after render. To be more specific, it runs both after the first render and after every update. In contrast to lifecycle methods, effects don’t block the UI because they run asynchronously.

If you are new to React, I would recommend ignoring class-based components and lifecycle methods and, instead, learning how to develop functional components and how to decipher the powerful possibilities of effects. Class-based components are rarely used in more recent React development projects.

If you are a seasoned React developer and are familiar with class-based components, you have to do some of the same things in your projects today as you did a few years ago when there were no Hooks.

For example, it is pretty common to “do something” when the component is first rendered. The difference with Hooks here is subtle: you do not do something after the component is mounted; you do something after the component is first presented to the user. Hooks force you to think more from the user’s perspective.

How is the useEffect Hook executed in React?

This section briefly describes the control flow of effects. The following steps are carried out when executing an effect:

- Initial render/mounting: When a functional component that contains a

useEffectHook is initially rendered, the code inside theuseEffectblock runs after the initial render of the component. This is similar tocomponentDidMountclass components - Subsequent renders: You can pass a dependency array as the second argument to the

useEffectHook. This array contains variables or values that the effect depends on. Any change in these variables will re-render the component. If no dependency array is given, the effect will run on every render - Cleanup function: You can also run an optional cleanup function inside the effect. It is used to clean up any resources or subscriptions created by the effect when the component is unmounted or when the dependencies change

- Unmounting: If a cleanup function is present, it is run and then the component is unmounted from the DOM

If one or more useEffect declarations exist for the component, React checks each useEffect to determine whether it fulfills the conditions to execute the implementation (the body of the callback function provided as the first argument). In this case, “conditions” mean one or more dependencies have changed since the last render cycle.

How do you execute side effects using useEffect?

The signature of the useEffect Hook looks like this:

useEffect(

() => {

// execute side effect

},

// optional dependency array

[

// 0 or more entries

]

)

Because the second argument is optional, the following execution is perfectly fine:

useEffect(() => {

// execute side effect

})

Let’s take a look at an example. The user can change the document title with an input field:

import React, { useState, useRef, useEffect } from "react";

function EffectsDemoNoDependency() {

const [title, setTitle] = useState("default title");

const titleRef = useRef();

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect");

document.title = title;

});

const handleClick = () => setTitle(titleRef.current.value);

console.log("render");

return (

<div>

<input ref={titleRef} />

<button onClick={handleClick}>change title</button>

</div>

);

}

The useEffect statement is only defined with a single, mandatory argument to implement the actual effect to execute. In our case, we use the state variable representing the title and assign its value to document.title.

Because we skipped the second argument, this useEffect is called after every render. Because we implemented an uncontrolled input field with the help of the useRef Hook, handleClick is only invoked after the user clicks on the button. This causes a re-render because setTitle performs a state change.

After every render cycle, useEffect is executed again. To demonstrate this, I added two console.log statements:

The first two log outputs are due to the initial rendering after the component was mounted. Let’s add another state variable to the example to toggle a dark mode with the help of a checkbox:

function EffectsDemoTwoStates() {

const [title, setTitle] = useState("default title");

const titleRef = useRef();

const [darkMode, setDarkMode] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect");

document.title = title;

});

console.log("render");

const handleClick = () => setTitle(titleRef.current.value);

const handleCheckboxChange = () => setDarkMode((prev) => !prev);

return (

<div className={darkMode ? "dark-mode" : ""}>

<label htmlFor="darkMode">dark mode</label>

<input

name="darkMode"

type="checkbox"

checked={darkMode}

onChange={handleCheckboxChange}

/>

<input ref={titleRef} />

<button onClick={handleClick}>change title</button>

</div>

);

}

However, this example leads to unnecessary effects when you toggle the darkMode state variable:

Of course, it’s not a big deal in this example, but you can imagine more problematic use cases that cause bugs or, at least, performance issues. Let’s take a look at the following code and try to read the initial title from local storage, if available, in an additional useEffect block:

function EffectsDemoInfiniteLoop() {

const [title, setTitle] = useState("default title");

const titleRef = useRef();

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect title");

document.title = title;

});

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect local storage");

const persistedTitle = localStorage.getItem("title");

setTitle(persistedTitle || []);

});

console.log("render");

const handleClick = () => setTitle(titleRef.current.value);

return (

<div>

<input ref={titleRef} />

<button onClick={handleClick}>change title</button>

</div>

);

}

As you can see, we have an infinite loop of effects because every state changes with setTitle triggers another effect, which updates the state again:

Dependency array items

The useEffect Hook’s second argument, known as the dependency array, serves the purpose of indicating the variables upon which the effect relies. This brings us to an important question: What items should be included in the dependency array?

According to the React docs, you must include all values from the component scope that change their values between re-renders. What does this mean, exactly?

All external values referenced inside of the useEffect callback function, such as props, state variables, or context variables, are dependencies of the effect. Ref containers (i.e., what you directly get from useRef() and not the current property) are also valid dependencies. Even local variables, which are derived from the aforementioned values, have to be listed in the dependency array.

The importance of the dependency array

Let’s go back to our previous example with two states (title and dark mode). Why do we have the problem of unnecessary effects?

Again, if you do not provide a dependency array, every scheduled useEffect is executed. This means that after every render cycle, every effect defined in the corresponding component is executed one after the other based on the positioning in the source code.

So the order of your effect definitions matters. In our case, our single useEffect statement is executed whenever one of the state variables changes. You have the ability to opt out of this behavior. This is managed with dependencies you provide as array entries. In these cases, React only executes the useEffect statement if at least one of the provided dependencies has changed since the previous run.

Let’s get back to our example where we want to skip unnecessary effects after an intended re-render. We just have to add an array with title as a dependency. With that, the effect is only executed when the values between render cycles differ:

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect");

document.title = title;

}, [title]);

Here’s the complete code snippet:

function EffectsDemoTwoStatesWithDependeny() {

const [title, setTitle] = useState("default title");

const titleRef = useRef();

const [darkMode, setDarkMode] = useState(false);

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect");

document.title = title;

}, [title]);

console.log("render");

const handleClick = () => setTitle(titleRef.current.value);

const handleCheckboxChange = () => setDarkMode((prev) => !prev);

return (

<div className={darkMode ? "view dark-mode" : "view"}>

<label htmlFor="darkMode">dark mode</label>

<input

name="darkMode"

type="checkbox"

checked={darkMode}

onChange={handleCheckboxChange}

/>

<input ref={titleRef} />

<button onClick={handleClick}>change title</button>

</div>

);

}

As you can see in the recording, effects are only invoked as expected when pressing the button:

It’s also possible to add an empty dependency array. In this case, effects are only executed once; it is similar to the componentDidMount() lifecycle method. To demonstrate this, let’s take a look at the previous example with the infinite loop of effects:

function EffectsDemoEffectOnce() {

const [title, setTitle] = useState("default title");

const titleRef = useRef();

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect title");

document.title = title;

});

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect local storage");

const persistedTitle = localStorage.getItem("title");

setTitle(persistedTitle || []);

}, []);

console.log("render");

const handleClick = () => setTitle(titleRef.current.value);

return (

<div>

<input ref={titleRef} />

<button onClick={handleClick}>change title</button>

</div>

);

}

We just added an empty array as our second argument. Because of this, the effect is only executed once after the first render and skipped for the following render cycles:

In principle, the dependency array says, “Execute the effect provided by the first argument after the next render cycle whenever one of the arguments changes.” However, we don’t have any argument, so dependencies will never change in the future.

That’s why using an empty dependency array makes React invoke an effect only once — after the first render. The second render along with the second useEffect title is due to the state change invoked by setTitle() after we read the value from local storage.

Utilizing cleanup functions

The next snippet shows an example demonstrating a problematic issue:

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

const interval = setInterval(function () {

setCount((prev) => prev + 1);

}, 1000);

}, []);

return <p>and the counter counts {count}</p>;

}

function EffectsDemoUnmount() {

const [unmount, setUnmount] = useState(false);

const renderDemo = () => !unmount && <Counter />;

return (

<div>

<button onClick={() => setUnmount(true)}>Unmount child component</button>

{renderDemo()}

</div>

);

}

This code implements a React component representing a counter that increases a number every second. The parent component renders the counter and allows you to destroy the counter by clicking on a button.

Take a look at the recording to see what happens when a user clicks on that button:

The child component has registered an interval that invokes a function every second. However, the component was destroyed without unregistering the interval. After the component is destroyed, the interval is still active and wants to update the component’s state variable (count), which no longer exists.

The solution is to unregister the interval right before unmounting. This is possible with a cleanup function. Therefore, you must return a callback function inside the effect’s callback body:

useEffect(() => {

const interval = setInterval(function () {

setCount((prev) => prev + 1);

}, 1000);

// return optional function for cleanup

// in this case acts like componentWillUnmount

return () => clearInterval(interval);

}, []);

I want to emphasize that cleanup functions are not only invoked before destroying the React component. An effect’s cleanup function gets invoked every time right before the execution of the next scheduled effect.

Let’s take a closer look at our example. We used a trick to have an empty dependency array in the first place, so the cleanup function acts like a componentWillUnmount() lifecycle method. If we do not call setCount with a callback function that gets the previous value as an argument, we need to come up with the following code, wherein we add count to the dependencies array:

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect")

const interval = setInterval(function () {

setCount(count + 1);

}, 1000);

// return optional function for cleanup

// in this case, this cleanup fn is called every time count changes

return () => {

console.log("cleanup");

clearInterval(interval);

}

}, [count]);

In comparison, the former example executes the cleanup function only once — on the mount — because we directly prevented using the state variable (count):

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect")

const interval = setInterval(function () {

setCount(prev => prev + 1);

}, 1000);

// return optional function for cleanup

// in this case, this cleanup fn is called every time count changes

return () => {

console.log("cleanup");

clearInterval(interval);

}

}, []);

In this context, the latter approach is a small performance optimization because we reduce the number of cleanup function calls.

Comparing useState and useEffect

Both useState and useEffect improve functional components and allow them to do things that classes can and that functional components can’t do without Hooks. To understand the difference between the two better, we need to first understand the purpose of both these Hooks:

Purpose of useState

The useState Hook is used to manage state variables within a functional component, akin to how this.state works in class components. With useState, you can declare and initialize a state variable, and the Hook provides a function to update its value.

Purpose of useEffect

We have already delved into useEffect in detail. In essence, it empowers functional components with lifecycle methods similar to those found in class components. You can employ useEffect to perform actions such as data fetching, DOM manipulation, or the establishment of subscriptions in response to component lifecycle events.

While both of these hooks serve distinct purposes, they are frequently used in conjunction. For instance, states are often utilized in the dependency arrays of an effect, allowing components to re-render when state changes occur.

Implications of prop and state changes

There is a natural correlation between prop changes and the execution of effects because they cause re-renders, and as we already know, effects are scheduled after every render cycle.

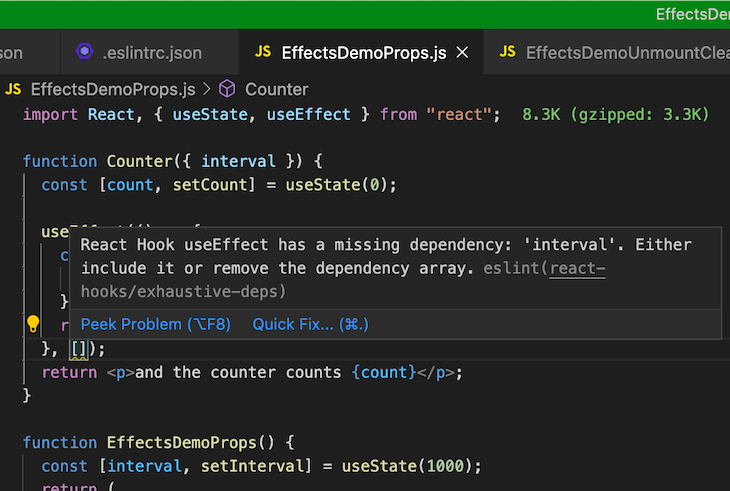

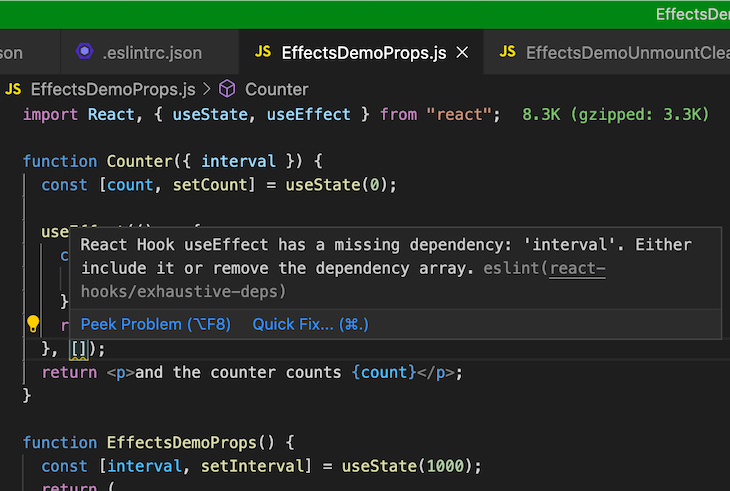

Consider the following example. The plan is that the Counter component’s interval can be configured by a prop with the same name:

function Counter({ interval }) {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

const counterInterval = setInterval(function () {

setCount((prev) => prev + 1);

}, interval);

return () => clearInterval(counterInterval);

}, []);

return <p>and the counter counts {count}</p>;

}

function EffectsDemoProps() {

const [interval, setInterval] = useState(1000);

return (

<div>

<input

type="text"

value={interval}

onChange={(evt) => setInterval(evt.target.value)}

/>

<Counter interval={interval} />

</div>

);

}

The handy ESLint plugin points out that we are missing something important: because we haven’t added the interval prop to the dependency array (having instead defined an empty array), the change to the input field in the parent component is without effect.

The initial value of 1000 is used even after we adjust the input field’s value:

Instead, we have to add the prop to the dependency array:

useEffect(() => {

const counterInterval = setInterval(function () {

setCount((prev) => prev + 1);

}, interval);

return () => clearInterval(counterInterval);

}, [interval]);

Now things look much better:

useEffect inside of custom Hooks

Custom Hooks are awesome because they lead to various benefits:

- Reusable code

- Smaller components because of outsourced code (effects)

- More semantic code due to the function calls of the custom Hooks inside of components

- Effects can be tested when used inside of custom Hooks, as we’ll see in the next section

The following example represents a custom Hook for fetching data. We moved the useEffect code block into a function representing the custom Hook. Note that this is a rather simplified implementation that might not cover all your project’s requirements. You can find more production-ready custom fetch Hooks here:

const useFetch = (url, initialValue) => {

const [data, setData] = useState(initialValue);

const [loading, setLoading] = useState(true);

useEffect(() => {

const fetchData = async function () {

try {

setLoading(true);

const response = await axios.get(url);

if (response.status === 200) {

setData(response.data);

}

} catch (error) {

throw error;

} finally {

setLoading(false);

}

};

fetchData();

}, [url]);

return { loading, data };

};

function EffectsDemoCustomHook() {

const { loading, data } = useFetch(

"https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts/"

);

return (

<div className="App">

{loading && <div className="loader" />}

{data?.length > 0 &&

data.map((blog) => <p key={blog.id}>{blog.title}</p>)}

</div>

);

}

The first statement within our React component, EffectsDemoCustomHook, uses the custom Hook useFetch. As you can see, using a custom Hook like this is more semantic than using an effect directly inside the component.

Business logic is nicely abstracted out of the component. We have to use our custom Hook’s nice API that returns the state variables loading and data.

The effect inside of the custom Hook is dependent on the scope variable url that is passed to the Hook as a prop. This is because we have to include it in the dependency array. So even though we don’t foresee the URL changing in this example, it’s still good practice to define it as a dependency. As mentioned above, there is a chance that the value will change at runtime in the future.

Additional thoughts on functions used inside of effects

If you take a closer look at the last example, we defined the fetchData function inside the effect because we only use it there. This is a best practice for such a use case. If we define it outside the effect, we need to develop unnecessarily complex code:

const useFetch = (url, initialValue) => {

const [data, setData] = useState(initialValue);

const [loading, setLoading] = useState(true);

const fetchData = useCallback(async () => {

try {

setLoading(true);

const response = await axios.get(url);

if (response.status === 200) {

setData(response.data);

}

} catch (error) {

throw error;

} finally {

setLoading(false);

}

}, [url]);

useEffect(() => {

fetchData();

}, [fetchData]);

return { loading, data };

};

As you can see, we need to add fetchData to the dependency array of our effect. In addition, we need to wrap the actual function body of fetchData with useCallback with its own dependency (url) because the function gets recreated on every render.

By the way, if you move function definitions into effects, you produce more readable code because it is directly apparent which scope values the effect uses. The code is even more robust.

Furthermore, if you do not pass dependencies into the component as props or context, the ESLint plugin “sees” all relevant dependencies and can suggest forgotten values to be declared.

Using async functions inside of useEffect

If you recall our useEffect block inside the useFetch custom Hook, you might ask why we need this extra fetchData function definition. Can’t we refactor our code like so:

useEffect(async () => {

try {

setLoading(true);

const response = await axios.get(url);

if (response.status === 200) {

setData(response.data);

}

} catch (error) {

throw error;

} finally {

setLoading(false);

}

}, [url]);

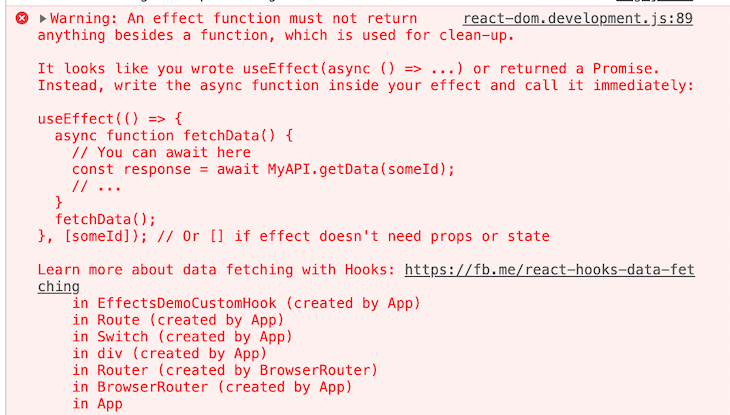

I’m glad you asked, but no! The following error will occur:

The mighty ESLint plugin also warns you about it. The reason is that this code returns a promise, but an effect can only return void or a cleanup function.

Additional useEffect examples

In this section, I’ll show you some handy patterns that might be useful when using the useEffect Hook.

Execute an effect only once when a certain condition is met

As we already know, you control the execution of effects mainly with the dependency array. Every time one of the dependencies is changed, the effect is executed. You should design your components to execute effects whenever a state changes, not just once.

Sometimes, however, you want to trigger an effect only under specific conditions, such as when a certain event occurs. You can do this with flags that you use within an if statement inside of your effect.

The useRef Hook is a good choice if you don’t want to add an extra render (which would be problematic most of the time) when updating the flag. In addition, you don’t have to add the ref to the dependency array.

The following example calls the function trackInfo from our effect only if the following conditions are met:

- The user clicked the button at least once

- The user has ticked the checkbox to allow tracking

After the checkbox is ticked, the tracking function should only be executed after the user clicks on the button once again:

function EffectsDemoEffectConditional() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const [trackChecked, setTrackChecked] = useState(false);

const shouldTrackRef = useRef(false);

const infoTrackedRef = useRef(false);

const trackInfo = (info) => console.log(info);

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect");

if (shouldTrackRef.current && !infoTrackedRef.current) {

trackInfo("user found the button component");

infoTrackedRef.current = true;

}

}, [count]);

console.log("render");

const handleClick = () => setCount((prev) => prev + 1);

const handleCheckboxChange = () => {

setTrackChecked((prev) => {

shouldTrackRef.current = !prev;

return !prev;

});

};

return (

<div>

<p>

<label htmlFor="tracking">Declaration of consent for tracking</label>

<input

name="tracking"

type="checkbox"

checked={trackChecked}

onChange={handleCheckboxChange}

/>

</p>

<p>

<button onClick={handleClick}>click me</button>

</p>

<p>User clicked {count} times</p>

</div>

);

}

In this implementation, we utilized two refs: shouldTrackRef and infoTrackedRef. The latter is the “gate” to guarantee that the tracking function is only invoked once after the other conditions are met.

The effect is rerun every time count changes, i.e., whenever the user clicks on the button. Our if statement checks the conditions and executes the actual business logic only if it evaluates to true:

The log message user found the button component is only printed once after the right conditions are met.

Accessing data from previous renders

If you need to access some data from the previous render cycle, you can leverage a combination of useEffect and useRef:

function EffectsDemoEffectPrevData() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const prevCountRef = useRef();

useEffect(() => {

console.log("useEffect", `state ${count}`, `ref ${prevCountRef.current}`);

prevCountRef.current = count;

}, [count]);

const handleClick = () => setCount((prev) => prev + 1);

console.log("render");

return (

<div>

<p>

<button onClick={handleClick}>click me</button>

</p>

<p>

User clicked {count} times; previous value was {prevCountRef.current}

</p>

</div>

);

}

We synchronize our effect with the state variable count so that it is executed after the user clicks on the button. Inside of our effect, we assign the current value of the state variable to the mutable current property of prevCountRef. We output both values in the JSX section:

When loading this demo, on initial render, the state variable has the initial value of the useState call. The ref value is undefined. It demonstrates once more that effects are run after render. When the user clicks, it works as expected.

When not to use useEffect

There are some situations in which you should avoid using useEffect due to potential performance concerns.

1. Transforming data for rendering

If you need to transform data before rendering, then you don’t need useEffect. Suppose you are showing a user list and only want to filter the user list based on some criteria. Maybe you only want to show the list of active users:

export const UserList = ({users}: IUserProps) => {

// the following part is completely unnecessary.

const [filteredUsers , setFilteredUsers] = useState([])

useEffect(() => {

const activeUsers = users.filter(user => user.active)

setFilteredUsers(activeUsers)

,[users])

return <div>

{filteredUsers.map(user => <div> {user.name} </div>)}

</div>

}

Here you can just do the filtering and show the users directly, like so:

export const UserList = ({users}: IUserProps) => {

const filteredUsers = users.filter(user => user.active)

return <div>

{filteredUsers.map(user => <div> {user.name} </div>)}

</div>

}

This will save you time and improve the performance of your application.

2. Handling user events

You don’t need useEffect to handle user events. Let’s say you want to make a POST request once a user clicks on a form submit button. The following piece of code is inspired from React’s documentation:

function Form() {

// Avoid: Event-specific logic inside an Effect

const [jsonToSubmit, setJsonToSubmit] = useState(null);

useEffect(() => {

if (jsonToSubmit !== null) {

post('/api/register', jsonToSubmit);

}

}, [jsonToSubmit]);

function handleSubmit(e) {

e.preventDefault();

setJsonToSubmit({ firstName, lastName });

}

}

In the above code, you can just make the post request once the button is clicked. But you are cascading the effect, so once the useEffect is triggered, it doesn’t have the complete context of what happened.

This might cause issues in the future; instead, you can just make the POST request on the handleSubmit function:

function Form() {

function handleSubmit(e) {

e.preventDefault();

const jsonToSubmit = { firstName, lastName };

post('/api/register', jsonToSubmit);

}

}

This is much cleaner and can help reduce future bugs.

React Server Components and UseEffect

React Server Components (RSC) let you render parts of your UI on the server — before any JavaScript is loaded in the browser. This means users see meaningful content faster, without a blank screen while JS bundles load.

But here’s the catch. Server Components don’t run in the browser. That means you can’t use Hooks like useState or useEffect inside them — because those only run after the component mounts on the client.

So what can you do?

-

Think of Server Components as data preparers — They fetch and pre-render content on the server

-

Think of Client Components as behavior handlers — They manage interactivity and effects like event listeners, animations, and local state

When to use useEffect with Server Components

You still use useEffect — just not in Server Components. Instead:

-

Use Server Components to fetch and format data on the server

-

Pass that data as props to a Client Component

-

Let the Client Component handle any client-only logic using

useEffect

Here’s a basic example:

// ServerComponent.jsx (runs on server)

import ClientComponent from './ClientComponent';

export default async function ServerComponent() {

const data = await fetchDataFromDB(); // runs on server

return <ClientComponent data={data} />;

}

// ClientComponent.jsx (runs in browser)

"use client";

import { useEffect } from "react";

export default function ClientComponent({ data }) {

useEffect(() => {

// This runs in the browser after mount

console.log("Client-side effect:", data);

}, [data]);

return <div>{data.title}</div>;

}

This separation improves performance, reduces JS bundle size, and gives you clearer control over where and how effects run.

Why mastering useEffect still matters

If you want to level up your React skills, understanding how useEffect works under the hood — and how to use it well — is essential.

Before Hooks came along in 2019, side effects lived in lifecycle methods like componentDidMount or componentDidUpdate. But useEffect shifts the mindset: instead of thinking in terms of “when” something happens, you think in terms of reactive dependencies — what changed, and what should happen because of it.

Adopting this mental model helps you:

-

Build a deeper understanding of React’s rendering behavior and lifecycle

-

Write more composable code with other Hooks like

useState,useRef,useCallback, anduseContext -

Spot unnecessary re-renders and optimize with tools like

React.memooruseMemo -

Manage side effects like data fetching, subscriptions, timers, or DOM manipulation cleanly and predictably

useEffect isn’t just a tool — it’s a lens into how your React app responds to changes. Mastering it helps you write components that are more efficient, reusable, and easier to reason about.

The post How to use the useEffect hook in React: A complete guide appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

This post first appeared on Read More