Is imitation theft or apprenticeship?

What two forgotten thinkers can teach us about voice, intent and AI-assisted work.

In 18th-century Europe, aspiring painters learned to paint by copying other artists.

They spent years in studios reproducing sketches and practicing technique. The point was to learn through repetition, and copying helped these aspiring artists understand what good looked like. Imitation was just part of the process.

Only after years of apprenticeship did painters begin to branch off.

Today, we’re talking about voice and style — something we used to develop through practice and feedback. Now that we have tools that help us produce faster than ever, we’ve failed to teach what good work looks like along the way.

When something feels like it was produced with AI, we discount its quality. We often blame the tool, or worse, we blame the person using it.

To bring some clarity, we’re bringing back two forgotten thinkers: Anna Laetitia Barbauld and Richard Bentley. Together, they offer a path forward.

I’m Nate Sowder, and this is unquoted, installment 7, a series about the people behind the ideas we can’t afford to forget.

Barbauld and the practice of imitation

In the late 1700s, Anna Laetitia Barbauld was writing poems, essays, and teaching at a time when few women had access to formal intellectual training.

She taught at Warrington Academy, a progressive school in England that served students excluded from elite institutions. Many of her pupils had never been taught how to write with structure or style.

Her method was simple: start by copying existing essays and poems. Over time, that helped students develop a sense of their own style by first understanding others’.

“The mind must be fed by imitation before it can create.”

To Barbauld, imitation was the path to originality.

Bentley and the structure of style

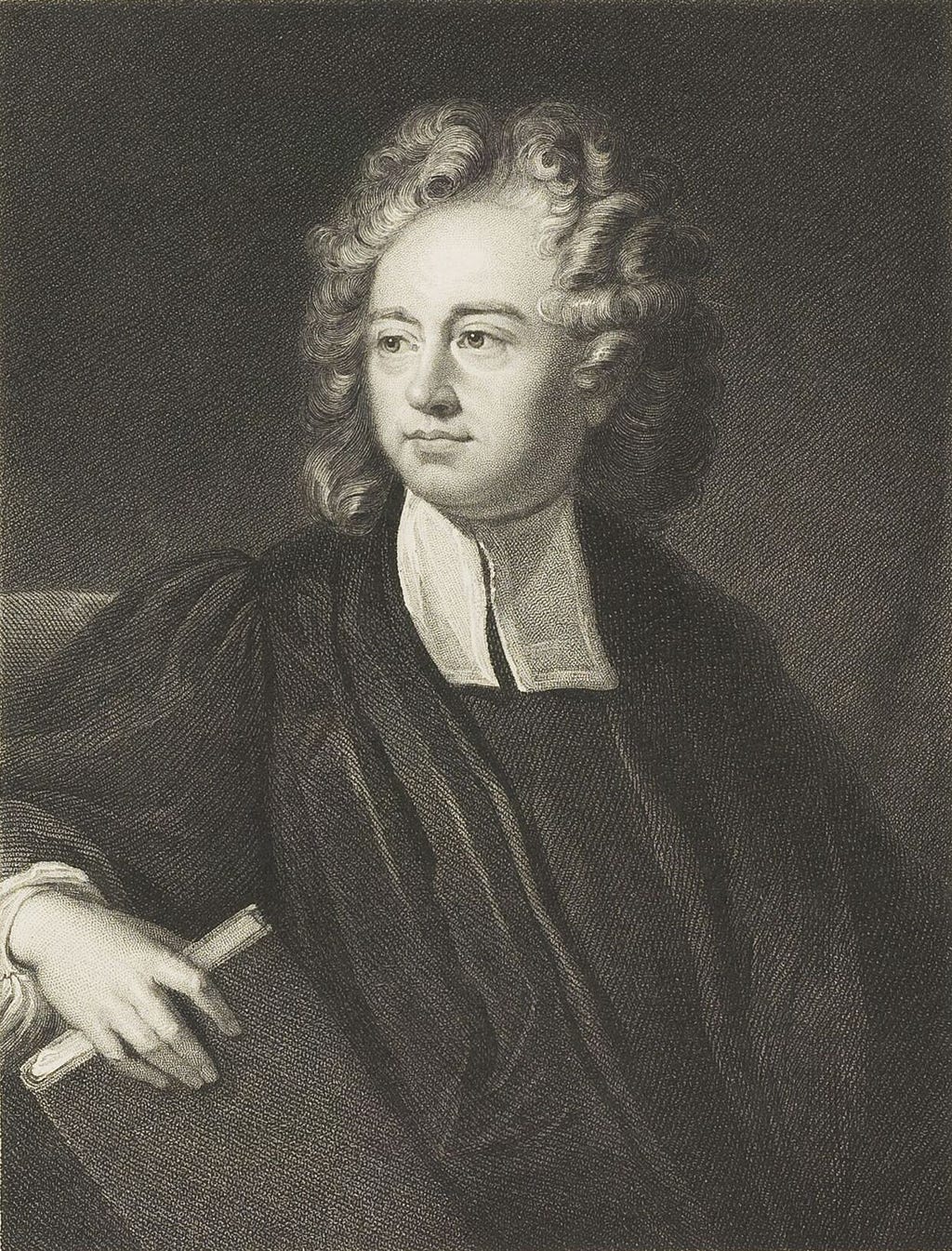

While Barbauld was helping students find their voice, Richard Bentley was working to detect where voice had gone missing.

Bentley was a classical scholar in the early 1700s who built a reputation on his ability to spot forgery. His most famous takedown was The Letters of Phalaris, a widely admired collection of ancient Greek writings once believed to be authentic. Bentley read them and disagreed.

When the syntax didn’t match, he realized the voice of the piece was all wrong. The references were off and the structure lacked consistency with the rest of the canon. Bentley could hear when something didn’t belong. He didn’t need proof in reference materials and records. Instead, he looked for a pattern he could follow.

He treated style as evidence and voice as something you could trace.

Why it matters

When you replace the process of developing expertise with productivity tools you stop teaching people how to build their voice. Instead, you hand them Mad Libs, templates and mandates like “use AI” but never define how, how much or to what end.

And then when the work feels too clean or like the person who wrote it… didn’t, we don’t ask what the person was trying to say.

We ask if they cheated.

That kind of suspicion kills growth. It tells people: Try this, but use it the perfect amount (without ever showing them what that looks like), and when they get it wrong, don’t coach them… judge them.

If AI becomes a source of shame, I think a lot of people will stop using it. They’ll avoid new opportunities, hide their process and aim for ‘safe and small’ outcomes.

What to do instead

This problem doesn’t fix itself. If we want people to use AI well, we have to define what that means, not just urge adoption and hope for the best. That means setting clear boundaries, offering real feedback and helping people grow into a voice that’s theirs (which can’t happen in a vacuum).

Barbauld gave us a blueprint for that kind of growth.

She showed that imitation, when guided, builds fluency. It helps people understand how ideas flow, how style works and how meaning holds together.

Bentley gave us the tools to listen.

He showed that voice isn’t invisible. It leaves a trail that can be studied, taught and refined (if we care enough to notice it).

Together, their teaching offers something AI tools can’t:

A path for learning how to sound like yourself.

We need less suspicion and more systems that help people build toward authorship.

Voice and style matter. Put in the work to develop your own.

Is imitation theft or apprenticeship? was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More