Contemporary design doesn’t just reflect nihilism, it creates it.

How what we build transforms our condition and shapes the very fabric of meaning.

It should come as no surprise to those paying attention that nihilism — the belief that life lacks inherent meaning — has become increasingly prevalent. However, these days it appears not as a defiant rejection of values, but as a quiet erosion of purpose met with a shrug of apathy.

Ends are replaced by metrics, conviction by convenience, and narrative by feeds. Secularism, politics, ideology, and technology are often blamed. However, another force hides in plain sight — design.

If one had to describe what nihilistic design looks like, it would be sterile, stripped of conviction, void of meaning, and soulless. Sound familiar?

Those same traits could be used to describe how many brands, websites, and apps appear today. No color, no texture, no shape— just flat, black and white, afraid to offend, and content to remain barren.

We like to think design reflects culture. The ornament of the Baroque in the 17th century, the geometric rigor of Art Deco in the 1920s, the neon excess of the 1980s — each seems like a mirror of the society that created it.

But what if this familiar story has it backwards? What if culture is not simply echoed in design, but shaped by it? What if the sterile and hollow interfaces we produce today are not passive reflections of nihilism, but active producers of it?

This idea has deep philosophical roots. Oscar Wilde once argued that life imitates art far more than art imitates life. Friedrich Nietzsche believed that aesthetics precede truth, that existence itself is justified only as an aesthetic phenomenon. Marshall McLuhan declared that the medium is the message, and Jean Baudrillard pushed it further, claiming that signs and images no longer reflect reality but generate it.

If this is true, the pattern is unmistakable—design doesn’t just record meaning, it scripts it. And once design withers, culture follows close behind.

From story to feed

Cultural forms once carried narrative. Cathedrals told stories in stone and glass. Novels and films offered beginnings, middles, and ends that gave coherence to life. Even broadcast television moved within familiar arcs.

Today that coherence is harder to find. Much can be said about the bland architecture of our cities and the thinning narratives of contemporary movies and novels, but one of the most concerning shifts has been in the evolution of streaming television.

Television experiences that once delivered episodes with self-contained stories now lean heavily on season-long arcs— arcs that may never conclude if the series is canceled. Stories hang suspended, deferred, or abandoned, and audiences grow accustomed to living with open loops, each pause just another cue to crave the next dopamine hit that never truly satisfies.

Nowhere are open loops more pervasive than the internet, especially social media. Here, design has abandoned narrative architecture altogether. Scroll-based feeds deliver hours of endless, unresolved experience. Search itself has become infinite — every query spawning new links, new threads, new rabbit holes without finality. These systems do not merely reflect shortened attention spans—they train us into them.

What’s lost in this shift is the collective experience. Once, cultural scarcity bound people together — shared stories, shared rituals, shared meanings that culminated. Meaning deepened because it was finite, because it felt resolved. Now we chase a superficial sense of significance in the infinite. But infinity never resolves. It offers no closure, only the perpetual lure of what lies just beyond.

The myth of neutrality

Minimalism and modernism complicate the story further. These movements, and their descendants in today’s flat digital interfaces, often parade as neutral. The grid, the sans serif, the clean white background — all claim to transcend culture, to present the universal. But neutrality is a myth. Every omission is a worldview.

By removing ornament, context, and symbol, design does not simply clear space for function — it establishes an aesthetic where emptiness itself becomes a virtue. This virtue is not neutral—it is rooted in Western Enlightenment ideals of rationality and order. A stripped-down interface tells us that depth is clutter, that meaning is noise, that efficiency is the highest good.

This unraveling of layered meaning now reaches even long-form writing. Articles like this, which should invite reflection, are met with readers possessed by the demand for expediency — brevity, punch, imagery. Platforms like Instagram and X (Twitter) have trained us to crave immediacy over depth. Pictures replace paragraphs, glances replace grasp, and culture learns to settle for surfaces.

Reason without conviction

What makes this drift even more insidious is the way design has cloaked itself in the language of reason. Research, usability testing, and A/B experiments all serve as proof that design is objective. Yet philosophy has long shown that reason cannot prove itself.

As Immanual Kant observed, reason always bumps against the limits of what it can justify. David Hume warned that no amount of empirical observation can bridge the gap from “is” to “ought.” Kurt Gödel demonstrated that even mathematics, the purest structure of reason, contains truths that cannot be proven within its own system. And Nietzsche reminded us that what we take as “truth” often conceals underlying values and power.

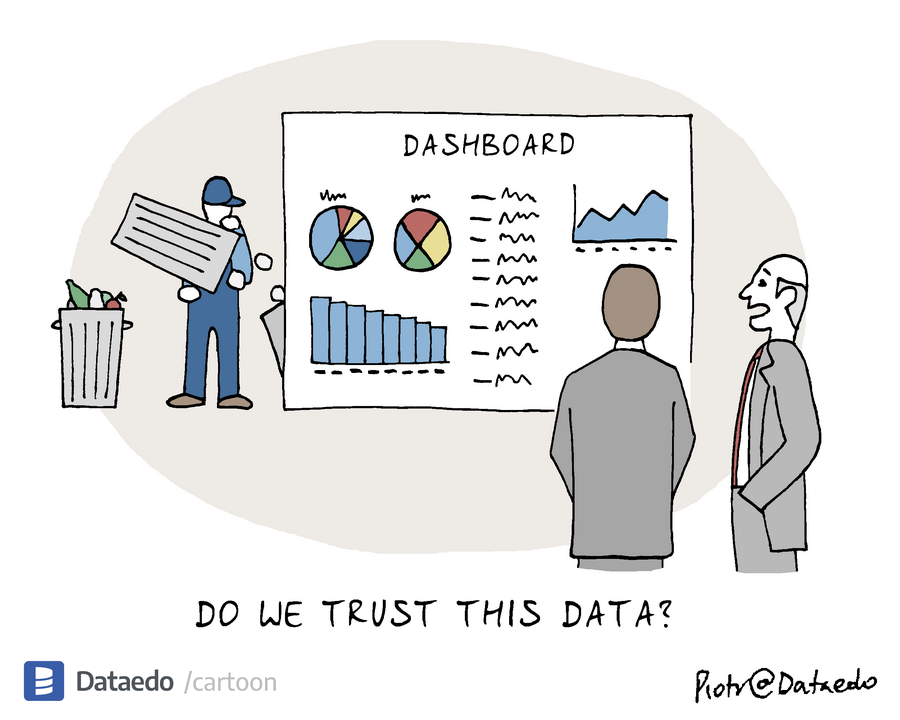

When design insists that data is its foundation, it forgets that even data rests on faith — in our senses, our instruments, and our frameworks. What presents itself as objectivity quickly slides into relativism, guided not by conviction but by whichever metric performs best in an experiment. Meaning evaporates in the process. Usability without story, efficiency without soul — these become the hallmarks of design that has abandoned belief in meaning itself.

AI and the acceleration of emptiness

Artificial intelligence is the logical extension of this trajectory — an engine built on reason based technology—data, pattern recognition, statistical inference — yet stripped of the conviction or belief that gives form meaning.

An AI-generated logo may look polished, but beneath the surface there is nothing. It is statistically coherent but culturally vacant, a reflection of averages without values.

Scaled up, these outputs flood culture with forms that only pretend to carry meaning. The danger is not simply their hollowness, but the way they train us to accept hollowness as normal.

Worse, their conversational mimicry — the illusion of a voice that “understands” — creates trust where none is warranted. We begin to trust the simulation of meaning rather than meaning itself.

When design can be generated in seconds, we learn to value speed over depth, convenience over conviction. The more we consume forms without substance, the more we adapt to their vacancy.

AI doesn’t just produce empty surfaces — it trains us to stop expecting meaning at all. And that quiet erosion of expectation is what makes it an accelerant of nihilism.

Design as an engine of nihilism

In contemporary design the inversion becomes clear. It doesn’t merely display nihilism — it drives it. Infinite feeds manufacture distraction. Minimalist sameness recasts emptiness as elegance. AI systems hint at human replaceability and then condition us to accept it.

Today’s interfaces aren’t passive reflections of culture. They script the way we see, think, and value. In their hollow repetitions they embed a lesson— nothing lasts, everything is disposable, and meaning is irrelevant.

Once these forms take hold, culture completes the circuit. Users absorb the cues and stop expecting depth. The less story, symbolism, or conviction design provides, the more indulgent such elements appear when they do surface.

The loop accelerates until the pursuit of meaning seems archaic. Emptiness is marketed as efficiency, even clarity. And here lies the danger—nihilism does not remain an abstract idea but becomes a lived condition.

At that point design doesn’t follow culture — it steers it, training us not only to live without meaning but to stop wanting it. That is how nihilism, once a philosophical diagnosis, becomes the default atmosphere of everyday life. And sadly, we are in the midst of such decay.

Toward a design of meaning

If this diagnosis is right, then design carries more responsibility than we often admit. It is not neutral. It is not merely reactive. It is formative. Which means that if design has played a role in producing nihilism, it can also play a role in resisting it.

The challenge is not to restore some lost objectivity — that foundation never existed. The challenge is to create values where none are given. Nietzsche saw this as the only way through nihilism — to become creators of meaning rather than its mourners.

Søren Kierkegaard, too, understood that escaping despair required more than reason—it demanded a leap of faith, an act of commitment that could not be justified in advance.

For design, that means reintroducing narrative into interfaces, reclaiming symbolism, and insisting that even in a secular and fragmented modern society, design can be an act of conviction rather than resignation. Meaning doesn’t emerge from an infinite feed of possibilities but from forms that resolve, gestures that culminate, and experiences that cohere.

Some designs already gesture in this direction. Duolingo, for example, transforms small units of repetition into a narrative of progress — each lesson resolves, each milestone carries symbolic weight. It shows that interfaces need not be hollow loops of engagement, but can script arcs of meaning that accumulate over time.

Another app that embodies a design philosophy that counters unbroken scroll and cultural drift is Wordle —with its one puzzle a day. Its strength lies in its boundary—you can’t binge it, and its closure is literal and shared.

Because the puzzle is the same for everyone, it becomes a point of convergence — a common experience across strangers and communities. The resolution is built in, and that closure is what gives it weight.

Designers cannot avoid their role in molding society. Every decision is ethical labyrinth. Every omission shapes culture. Every interface is an argument about how meaning works. If our designs are hollow, they will train us into hollowness. If they carry conviction, they will cultivate conviction.

Choosing meaning

We like to say design reflects culture, but that’s only half the truth. Culture also reflects design. And the interfaces we are building today don’t just echo nihilism — they embed it, normalize it, and accelerate it. The real question isn’t whether design has agency, but whether designers are willing to own the meanings they create — or the voids they leave behind.

Part of the work is rhetorical. Designers can learn to reframe meaning as a kind of metric in itself — arguing that coherence builds retention, that conviction breeds loyalty. If the industry only speaks numbers, then one task is to translate values into that language without losing the values themselves.

If we refuse that responsibility, our interfaces will go on teaching the same lesson, swipe after swipe—that meaning itself is negotiable, optional, disposable. And the more we live inside those lessons, the more we risk losing the very capacity to imagine life beyond the abyss.

Don’t miss out! Join my email list and receive the latest content.

Contemporary design doesn’t just reflect nihilism, it creates it. was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More