Why great narratives beat OKRs in early-stage products

If you’ve ever worked in or around startups, you’ve definitely seen it: a small team, new funding, great enthusiasm, and a whiteboard full of objectives and key results (OKRs). Everything appears polished, strategic, and “grown-up.” However, for early-stage products, the polish might be a trap.

In the early, messy, uncertain stages of product development, narrative always outperforms strategy. A compelling story not only guides your team, but it also persuades investors, early adopters, and potential hires to believe in something that doesn’t exist yet. Strategy and OKRs have their uses, but they’re tools for increasing clarity, not creating it.

This article explores why early-stage products should prioritize storytelling over a rigid goal-setting framework. It goes on to demonstrate how a compelling narrative can attract investors and encourage early adopters, while also outlining when to transition into structured strategies as the product matures.

The problem with over-optimizing early

Many early-stage startups fall into the trap of acting like big organizations before they have anything to scale. They create quarterly OKRs, establish acquisition, and conduct “data-driven experiments” without a steady stream of customers to examine.

Here’s what generally occurs:

- Disconnection from stakeholders — Investors and partners only hear numbers, not your vision. Those statistics lack context since they’re not anchored by a story

- Lack of early adopter engagement — Potential users aren’t concerned with your KPIs; they’re concerned with whether your solution answers an issue that they’re personally experiencing

- Team misalignment — OKRs divert attention to separate tracks. In a five-person team, this promotes silos rather than togetherness

Take a small startup that establishes an ambitious OKR: “Acquire 5,000 users by Q1.”

The problem with this is that they haven’t figured out why people would use their product in the first place. Every meeting devolves into a metric debate, and morale drops when targets are consistently missed. They didn’t need additional optimization, they needed a unified story about why the product was important.

The power of narrative in early stage products

Now, let’s compare that to teams that start with a story. Consider this simple narrative: “We help remote teams feel like they’re in the same room.” This is way more more effective than any early growth target because it:

- Unifies the team around a common goal

- Indicates to investors why this product is worth their attention

- Engages early adopters who recognize themself in the story and want to be a part of it

Narratives work because they can convey meaning in ways that numbers cannot. In the early phases, most numbers are too little to matter. However, a compelling story can outperform its weight, changing perceptions and opening doors that mere statistics cannot yet support.

Story vs. strategy: Key differences

Your story and strategy are both important, but their roles vary depending on the stage of a product’s development.

The story is what drives the early days. It instills belief, explains why the product is important, and provides your team, investors, and early adopters with something to rally around. At this point, most statistics are less meaningful. Your story bridges the gap by triggering emotional responses and providing a vision of the future.

Strategy and OKRs, on the other hand, become relevant once that belief is established. They focus on coordinating execution, monitoring progress, and scaling what already works. OKRs are great for keeping larger teams on track and optimizing existing systems.

The danger comes when they’re applied too early. The story answers the question, “Why should anyone care?” Strategy answers, “How do we get there consistently?”

You need both, but they need to arrive at the right time. Without a story, strategy risks becoming hollow. Without a strategy, the story risks staying vague and ungrounded.

When to shift from story to strategy

OKRs and structured strategies will eventually become important. The trick is understanding when to make that transition. Moving too soon suffocates your narrative. Move too late, and chaos ensues.

This practical checklist could be used to determine if it’s time to go from story-first to strategy-driven:

- Do you have a clear product-market fit (customers return without any prompting)?

- Is your team greater than ten and struggling with alignment?

- Are investors or stakeholders requesting formal reporting beyond the vision pitch?

- Are you expanding operations (customer support, infrastructure, and staffing) beyond what the founders can handle directly?

- Do you have enough user data to make analytics and optimization meaningful?

If two or more of these are true, it’s time to start layering in OKRs. Until then, keep leaning on the story.

Case studies of effective narratives

To demonstrate how narrative can drive traction in the early stages, let’s explore two well-known success stories: Airbnb and Figma, and how each company’s emphasis on storytelling generated momentum before strategy took over.

Airbnb: Selling a vision before metrics

Airbnb started in 2007 when its founders rented out air mattresses to cover rent. At the time, “people paying to stay in strangers’ homes” was almost absurd:

The narrative: Instead of focusing on early growth metrics, the founders rallied around the idea of “belonging anywhere.” They positioned Airbnb not as a booking site, but as a new way of experiencing the world.

The impact: This narrative appealed to both early adopters and investors. Users who were initially suspicious about “couch surfing 2.0” were instead drawn to the larger notion of connection and belonging. Investors invested not because of the hockey stick graphs, but because they believed in the story.

Transition: After the platform gained traction and the team grew, Airbnb added OKRs for trust, supply, and booking volume, but only after the story had established the brand.

Key takeaways:

- Lead with a mission people can connect to emotionally

- Use narrative to normalize unconventional behavior (staying in strangers’ homes)

- Delay metrics until your story earns enough believers

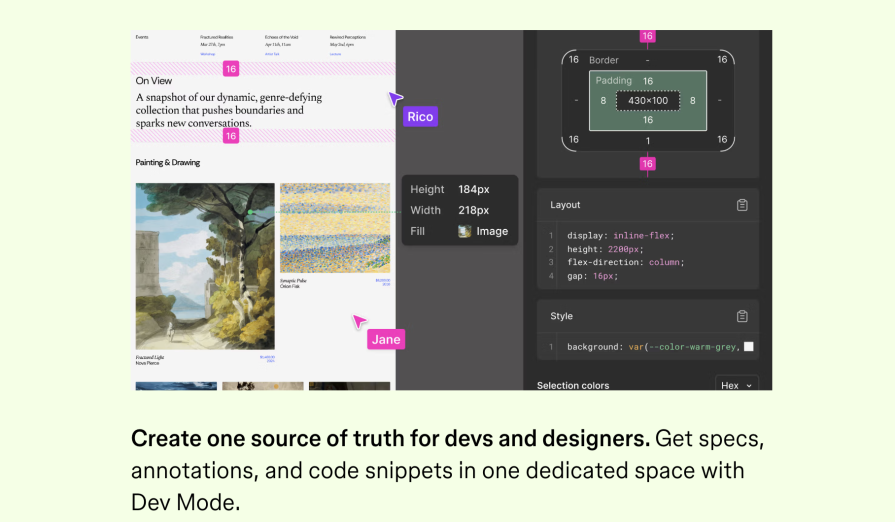

Figma: A story that scaled with the product

Figma entered a crowded design tool market dominated by Adobe and Sketch. It was late to the game and had no right to win on features alone:

The narrative: Figma offered a story of collaboration rather than direct competition with Adobe. Its message is: “Design should be multiplayer.” This was more than just tools; it was about a new style of working.

The impact: That story spread organically. Designers frustrated with file-sharing and version conflicts instantly understood the value. Early adopters championed the product because it matched their lived frustrations. Investors saw a clear wedge into the market.

Transition: When usage skyrocketed, Figma introduced OKRs for enterprise adoption, integrations, and infrastructure expansion. However, the narrative of multiplayer design remained vital even as the company grew.

Key takeaways:

- Don’t compete on features alone; compete on narrative

- Frame your product as part of a bigger cultural or workflow shift

- Keep the story alive even as OKRs take over

The other side: Cautionary tales

Of course, not every startup gets this balance right. Everpix and Webvan are reminders of what can go wrong when metrics and optimization overshadow narrative and early user connection.

Everpix: Great product, weak narrative

Everpix was a photo startup that automatically organized users’ images. The product was beautifully designed and technically strong.

The team obsessed over polish, features, and metrics such as engagement. However, they failed to tell a clear story about why people should use it over free or familiar alternatives (like Apple Photos). Despite positive reviews and a small but loyal user base, Everpix couldn’t grow fast enough to sustain itself. Investors pulled back, citing unclear positioning and a lack of difference.

Instead of evolving into a stronger story about emotional value (memories, relationships), Everpix focused more on product polish and eventually shut down in 2013.

Webvan: Scaling goals without narrative

Webvan, a dotcom-era grocery delivery service, raised nearly $800M and scaled aggressively in the late 1990s.

The company was focused on aggressive expansion metrics, launching cities, building warehouses, and meeting growth targets. However, it never addressed the essential question: Why would customers prefer Webvan over traditional food shopping?

Expansion had overtaken adoption. Costs skyrocketed while users lagged. By 2001, Webvan had declared bankruptcy, becoming one of the most memorable dotcom collapses. It introduced a large-scale strategy and optimization before proving the narrative with early users.

Final thoughts

Your story isn’t just fluff when it comes to early-stage products — it’s necessary for survival. Although numbers can be motivating, they start out insignificant and can take a long time to scale. What people remember, repeat, and unite around is your story.

Airbnb and Figma demonstrate that story-driven companies can captivate hearts long before spreadsheets. On the other hand, Everpix and Webvan demonstrate that pursuing optimization too early can lead to failure, no matter how well-funded or polished the product.

The lesson here is to begin with a narrative, then layer in strategy when it’s appropriate. Because, in the early stages, a great narrative not only outperforms OKRs but also supports them later.

Featured image source: IconScout

The post Why great narratives beat OKRs in early-stage products appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

This post first appeared on Read More