Beyond random: why systems behave in predictable ways

Hidden patterns of system behavior

Understanding the feedback loops and recurring designs that govern our lives

Systems don’t behave randomly. They behave based on their design. As a result, many systems, even those found in nature, exhibit frequent, common behaviors. Moreover, these behaviors will typically manifest the same problems and issues, so much so that we may even name and categorize them. These are sometimes called archetypes, but I prefer to call them familiar system mechanisms. For designers they are important to know, recognize, and avoid.

Why Feedback Matters

Feedback refers to the way systems communicate with individuals. By providing information about the system state and its performance, feedback enables the individual to make decisions (or evaluate system recommendations). It is perhaps one of the most important aspects of systems design.

Feedback is critical for building system resilience; when errors occur, a system should give feedback about the error and allow for an immediate response to correct the error.

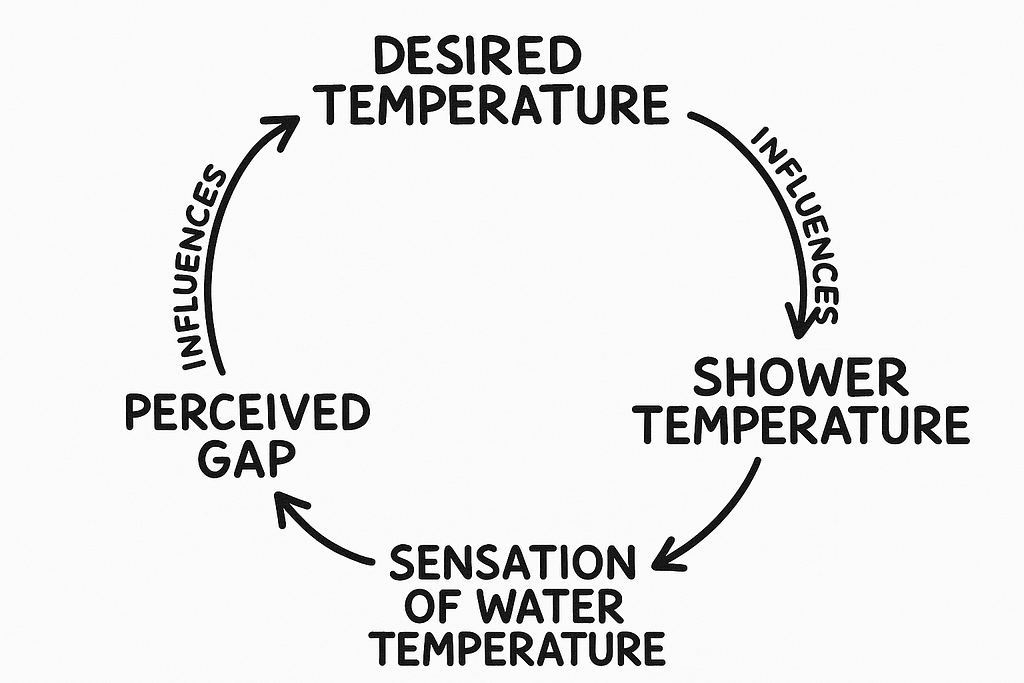

Think about the simple act of adjusting your shower water temperature. You turn the handle, stick your hand in the water stream, and receive immediate feedback about whether you need to adjust further. This feedback loop — action, measurement, adjustment — is fundamental to how we interact with systems.

But not all feedback is immediate. And that’s where things get interesting.

The Power of Recognizing Familiar System Mechanisms

Recognizing familiar system mechanisms (FSMs) is important for several reasons:

First, by recognizing them, you can quickly and accurately predict how the system will act. This knowledge enables you to situate yourself in the position of highest leverage to alter or improve the output of the system, or to use it to your greatest advantage.

Second, when FSMs fail, they typically fail in a common and familiar way. This particular way is called a failure mode. Correctly recognizing and categorizing an FSM will enable you to prevent and guard against the most common failure modes quickly and with little effort.

Third, FSMs provide clarity and agency in the face of complexity. Many problems found in life and business are different manifestations of similar system mechanisms. To recognize this is to empower yourself. As Peter Senge writes in “The Fifth Discipline:”

“Systems archetypes [FSMs] reveal an elegant simplicity underlying the complexity of management issues. As we learn to recognize more and more of these archetypes, it becomes possible to see more and more places where there is leverage in facing difficult challenges and to explain these opportunities to others.”

While Senge’s focus was explicitly on management and business, it’s clear that the same principles apply to other areas of life, even in our personal daily enterprises.

Three Familiar System Mechanisms You Need to Know

Mechanism #1: Balancing Process with Delay

In this mechanism, an actor adjusts the system controls in response to delayed feedback. If they are not aware that the system has a feedback delay, or misjudges the delay, they will over or under adjust the controls, or become discouraged from lack of change in the controls.

A shower provides a great example for this. We all know that the controls of the shower are not instantaneous and that the shower has a startup time associated with getting hot water to the showerhead. Because of experience we allow some time for the system (shower controls, plumbing, hand) to register a change before making further adjustments. And yet despite ample experience, we’ve all been surprised by an icy or excessively hot stream of water as we’ve mistakenly adjusted the controls.

The lesson to be learned from this type of scenario is that aggressiveness increases risk and volatility. Stock market bubbles are a macro-level phenomenon of the same mechanism at play. Investors see delayed feedback from their actions, panic, and over-correct, creating wild swings in valuation.

This mechanism shows up everywhere:

- Dieting and weight loss (results take weeks to show)

- Learning new skills (improvement feels slow initially)

- Economic policy (effects take months or years to materialize)

- Exercise routines (strength gains and muscle growth have delayed feedback)

Mechanism #2: Limits to Growth

In this system mechanism, (of which a famous, 1972 paper was written) the system grows organically, but eventually encounters a limit to continued growth. Actors within the system may be tempted to ignore early signs of the limit to growth or discount it as trivial because of the current success. As the limit goes unaddressed, growth continues to slow. The way for the system to continue to grow is to remove the limit.

In the NBC sitcom, The Office, Michael Scott starts his own paper company to compete against his former employer, Dunder Mifflin. By undercutting prices, he steals away Dunder Mifflin’s customers, but as he looks to expand his business, he’s confronted by a startling reality: the prices that are making him successful are also putting him out of business.

The lesson of this mechanism is to address limitations early to avoid roadblocks later.

Mechanism #3: Tragedy of the Commons

In the tragedy of the commons, actors within a system all have access to shared but limited resources. They use this resource for their individual needs, and since the resource is free to them, they benefit from its use. As more people become aware of the free, beneficial resource, more people start using it, and the advantage diminishes until it is obliterated.

Nobel Prize winner Thomas Schelling explains in “Macromotives and Microbehavior”:

“‘The commons’ has come to serve as a paradigm for situations in which people so impinge on each other in pursuing their own interests that collectively they might be better off if they could be restrained, but no one gains individually by self-restraint.”

Colleagues sharing a drive at work to backup your computer is one manifestation of the familiar mechanism, as is what happens when too many devices are playing at once on the home Wi-Fi. Or when Netflix calls you out for using the service in too many locations.

The lesson of this familiar system mechanism is to recognize the “commons” and create some level of self-regulation or peer-monitoring to ensure the common resource remains useful for all.

The Role of Systems in Decision-Making

Systems do not just have an overriding impact on human behaviors but also have an oversized impact on the way we frame problems, evaluate choices, and make decisions.

One of the best demonstrations of this comes from the popular 2008 book “Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness.” Authors Richard Thaler (Another Nobel Prize Winner) and Cass Sunstein make it clear that the way decisions are made has a lot more to do with the context and systems that surround the decision than the person’s own preferences or free will.

The book is full of quotes that testify to the reality of the impact systems have on human behavior, including decision making:

“People have a strong tendency to go along with the status quo or default option.”

“First, never underestimate the power of inertia. Second, that power can be harnessed.”

“The first misconception is that it is possible to avoid influencing people’s choices.”

Their main point is critically important: behavior is impacted by systems.

Why This Matters for Your Life

We do not make our decisions in a vacuum. This is neither a good thing nor a bad thing. Our interaction with the environments and systems around us constrain and limit our decisions and behaviors. With this awareness, we give ourselves greater personal and individual agency.

Recognizing the patterns that make up FSMs helps simplify complexity, predict outcomes, and identify leverage points for meaningful change. Rather than reacting blindly to problems, understanding FSMs enables smarter, more strategic responses.

Whether it’s designing better personal habits, improving workplace processes, or simply understanding why certain patterns keep repeating in your life, recognizing these familiar mechanisms gives you the power to work with the system rather than against it.

The feedback loops are always there. The patterns are always present. The question is: will you learn to see them?

Beyond random: why systems behave in predictable ways was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More