We are entering the era of thought-shaped software

We are in a transitional period: from the era of software shaped like household objects to the era of software shaped like thought.

We have a big choice to make: we’re about to jump into a new era of technology — meaning different values, expectations and powers — and we need to choose what it looks like.*1 The transition itself is unavoidable, but the details are up to us. Today we must chose between a. a future where our software environment has a thought-shaped interface on top of all the old kludge, or b. a future where software is built from the ground up to represent our thoughts, not twist or control them.

Here’s how I plot our society’s timeline when it comes to computers:

- Computer-shaped (1941-1979): The first way we communicated with modern, digital computers was entirely on their terms

- Thing-shaped (1979–2026): Then we interacted with computers through imagined household objects (e.g. documents, clipboards, desktops)

- Thought-shaped (2026–): In the future, computer interfaces will be shaped like human thought

This dam has to break. It happens that AI is doing a lot the breaking: LLMs’ natural language interface is the first of a set of thought-shaped technologies to come into common use. Indeed, we need to make sure that we don’t end up with a “same circus, different clowns” story, with a thin layer of natural language (AI/LLMs) on top of the same old exploitation and insult we’re used to from technology.

During times of transition like this, we (the users, people who care but are told to shut up) have the opportunity to take things not usually subject to change — systems, norms, standards — and make them better. I think that our computer interfaces (operating systems, applications, user interfaces) are inhumane, and today we have the opportunity to demand humanity.

I invite you to take a trip with me through the previous eras of technology. Then we can think together about what the new era might look like. Let me explain how we should navigate, before we begin.

Navigation

There are two things to consider when navigating among these eras:

1. Invisibility

It might not be immediately and intuitively clear why I make a judgement about, say, the shape of a user interface. To many, even most, the nature of modern computer interfaces is just how they are. I’m here to say that modern computer interfaces are peculiar — just as your regional accent sounds to your fellow citizens, while to you it sounds normal.

Computer interfaces are imaginary, meaning that it’s not always obvious when they are wrong. Unlike a broken limb or a mountain floating in the sky, it’s hard to say that something is wrong when there’s little or nothing to which one can point and say “this is right.”

2. Why are we about to enter a new era?

Why is technology progressing like this, and why this transition? In my view, technology closer to the shape of human thought is more powerful and enjoyable to use — our desires will pull technology and interfaces in this direction.

Meanwhile, LLMs with chat-style interfaces are getting very popular. These interfaces are pushing things forward because they are thought-shaped, and seem to be helping people to demand more straightforward and approachable interfaces.

Our technology is of course held back by those with an interest in keeping things as they are, usually because:

- They sell things that work in the old way

- They control a department that does things in the old way

- They can’t get their head round the new way

Be vigilant, finally, for fake or dubious progress. For instance, the smartphone boom starting in the mid-noughties gave people something more accessible, but under excessive control by supercorporations. Progress is not a single line, it’s a delta.

Ted Nelson

Finally, I beseech you to watch and read anything you possibly can by Ted Nelson. More or less everything he predicted has come true, and where technology deviated from his recommendations it is thus weaker. His Ted talk — 1990! — is a great place to start:

https://medium.com/media/6bc8bc7e01a04dafce0f8fb7f47086cb/href

So, to the timeline:

The computer-shaped era

1941–1979

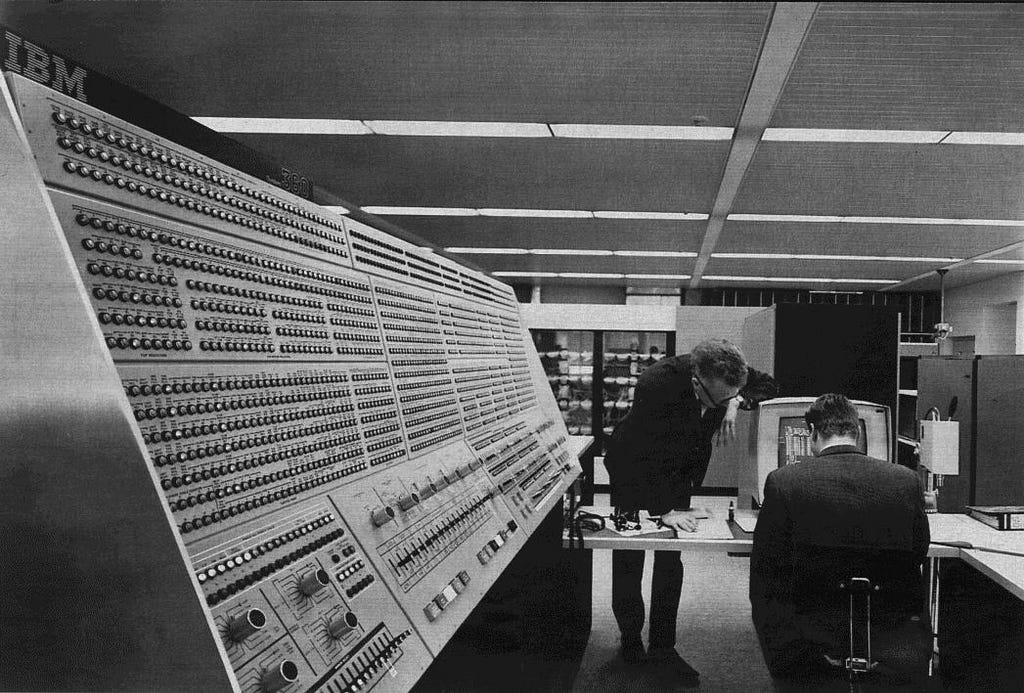

Defining machine: IBM 360

This era is characterized by the fact that, to work with a computer, you needed to do so on the computers terms — with little deviation. If you look at a mainframe or minicomputer, manufactured before the year 2000, it will likely have a lot of switches on the front panel.

Some of these switches allow you to enter bits directly into the computer’s memory. Each switch controlled a single bit in a given byte, and you flipped the switch up to set the bit as 1 and down for 0.

Editing bits in a byte has little to do with whatever task (like writing or mathematics) you have mind and everything to do with changing the value of bits: a computer’s reason for being. Front panels like this, along with punch cards, and paper and glass terminals, and more, are all examples of computer-shaped interfaces.

The defining user interface convention of this era was the IBM System 360: a colossal, expensive mainframe system. People ran applications on the 360, but users usually created these themselves. IBM offered several operating systems, but nothing recognizable to a modern user.

This created a caste of computer professionals to do the work, who naturally adopted a rarefied mindset. These people, having to descend to the level of bits, often never surfaced — or when they did they involved much of the computer’s rigid, sequential way of being into their own.

Ted Nelson called this “punch card brain.” The mindset is alive today, such as those who act as though one is calling for personal nuclear weapons or the abolition of the British monarchy when we inquire politely about being a little less hierarchical in how we organize data.

This era was venerable, however, in that it avoided a few pretenses common today: there was no pretend “document” slapped over the underlying data. Back then, what you got is what you get.

All in all, this era made us think of the computer as big, difficult, and separate. It made repetitive, sequential tasks faster. With nuanced, interleaved thinking, it helped little or not at all.

The thing-shaped era

1979–2026

Defining machine: Macintosh

Next came the era of computing in which we worked with computers through digital versions of common office or household objects. For instance the document, clipboard, desktop, file, folder, etc.

This is in part an apology — for the alienation of the last era — and condescension, in that they went so far as to believe that non-computer people couldn’t understand information and system concepts in themselves, but needed a metaphor to connect it an object in their home or office.

“See that thing on the screen? [a word processor] It’s like a piece of a paper in the computer.”

The nature of what runs on machines in this era is indeed that of a figleaf and/or a red herring: often colorful, sometimes in motion or noisy, often with fake personhood (see Clippy). Most of what we touch every day: separate applications with incompatible data, warring operating systems, “windows” feel like what the computer actually is but are at best an annoying expedient and at worst a cynical trap.

We didn’t need these metaphors as much as they said we did

Firstly, this attitude is wrong in itself: most people with jobs must understand and organize numerous formal systems. Of the top of my head:

- Knitters must read, understand and realize knitting patterns.

- Store clerks must enter data purchase information and mange inventory.

- Musicians must manage time, pitch and ensemble; in the case of Jazz and improvised genres, they must do so on the fly.

The popular media present computers and their central processing units (CPUs) to us as unfathomably complex. But consider this: a computer is at base doing nothing more than turning on and off a certain set of circuits over time.

A knitter does just the same, working from a knitting pattern that tells them which type of stitch they should do, in a sequence. Some of you will know already that the modern punch card was first used for weaving machines, developed later into a general data medium.

Inconsiderate techies look at a knitter, clerk or musician and say “those fluffies can’t understand computers,” when those fluffies work within the same formal system every day. As with many other subjects — particularly mathematics — I think that much of our fear of computers comes not from their nature, but from how they’re presented.

Metaphor hangover

Secondly, these “metaphors” tend to stick around and cause trouble. Consider this: maybe there is someone — not quite grasping the function of a word processor on a computer — who would benefit from me saying, “it’s a bit like a paper document, on the computer.”

But this metaphor sticks to the digital simulacrum: we act as though digital documents are bound by the limitations of paper documents. For instance digital documents and their parts can in theory be freely intermixed and reused, but there are practically no good digital tools for this purpose.

More brutally, we reify one of the most crushing limitations of documents: pages. Put it this way, if you had a document (this one, for instance) would you say to yourself, “this would be better if the system I use to read it simulated it being split over some number of pages.” Indeed, if you were of that opinion, this feature should obviously be optional — and be off by default.

This is why I try to avoid the word “document” altogether. I don’t think there’s anything lost by referring instead to particular sets of smaller structures (sections, paragraphs, etc.) that refer to meaningful literary ideas and that can be freely recombined into any number of “works” that we show to others.

Let’s say that I write an article: is it a document? Yes. But what if I then make it instead a section within a larger article: is it still a document, or is it nullified by the larger form? These are not serious questions: they’re distractions that come up because we’re thinking about the problem in the wrong way.

In my view, any arrangements of text (combinations, subsets, etc. regardless of what came first) are equally valid (though not necessarily equally interesting). We need a new word (perhaps “work”) to replace “document” in referring to a particular thing we want to show to someone else.

Computers are indeed our best chance of building information systems shaped like our thoughts. Our thoughts — which we can associate freely, combining any one thought with any others or parts thereof, creating connections in any shape — have never fit into human information systems, which insist material must be linear, tabular or hierarchical.

But we threw away this chance for a generation by simulating paper and other household objects. The next era will give us another chance.

The thought-shaped era

2026–

Defining machine: to be determined

We are in the transitional period between the thing-shaped and thought-shaped eras, today. But you might be asking: how is thought shaped, then?

Thoughts, or more generally ideas, have abstract shapes in the same way that physical objects do. For instance, the following ideas are tree shaped:

- The evolutionary “tree of life” (after a certain point)

- Organizational hierarchy

- Many computer programs

If we accept this, we realize also that:

- Thoughts can be any shape

- If a shape is unfamiliar to us, the thought will be hard for us to grasp

- Likewise, things come naturally when we have their shape in our minds

- And we learn new shapes over time

Disconcertingly, people can sometimes forget about certain shapes or come to reject them: corporate types sometimes, for instance, are troubled by network graphs and insist everything should be hierarchical. Oddly, otherwise flexible systems like Unix enforce hierarchy of the filesystem: this is unnecessary, but you get so used to it that when someone poses the idea of doing something different, it feels wrong.

Indeed, the hierarchical Unix filesystem is problematic because it precludes many valid ways of thinking about information — it is, thus, not thought shaped.

Why does this matter?

It hurts us when our interfaces are not shaped like our thoughts because you can only control a system (say a piece of airspace around an airport) if the following are true:

- Your control system contains a model of the system you want to control, such as an air traffic control map.

- The model has a part for every aspect of your system that you care about, your map needs a model plane (today digital) for every real plane in your airspace.

Just as an air traffic controller denied a map or enough detail to track every plane is sure to fail — I say that if your work is dotted with abandoned, disorganized or twisted writing projects, there’s nothing necessarily wrong with you or your ideas, only with your software.

Software systems which — like an effective air traffic control system — have a one-to-one correspondence between the model and the aspects of your writing or information generally that you care about, I call thought-shaped.

Taxonomy of key shapes

By my reckoning, there are four or five shapes that are important for our discussion of thought:

- Linear: when one thing follows the next, with no one thing being connected to more than two others

- Tree/Hierarchical: when there’s only one pathway between two things

- Tabular: made by arranging several linear structures into ranks

- Graph/hypergraph: with a graph, you can connect anything you like; some people distinguish between “nodes” that are connected by “edges.” Graphs connect only nodes, hypergraphs connect edges, too

Encoding

Most of us accept the validity of these abstractions, but there are many ways to express them. Here I defer to Kant, who said that there are three modes of thinking, allowing us to:

- Separate ideas from anything irrelevant (abstraction)

- Combine several ideas into a new idea (combination)

- Set several ideas side by side and look at them together (relation)

We can use these principles as a system to build idealized forms of either general structures (e.g. a tree) or particular structures (e.g. my network of friends). Specifically:

- We start by imagining in our system that there are things.

- Each thing is unique.

- Each thing can be divisible into other things or indivisible.

- The process of dividing things is called abstraction. I might forget about the leaves and the particular number of branches on a given oak, and think only about the tree structure, say.

- There are two methods by which we make new things from existing things:

- Combination, for instance combining two paragraphs into a section.

- Relation, such as making a link between a sentence in one article and a paragraph in another, that we might consider them together.*3

We can use the above to build all of the shapes described above:

To create a linear shape one can either:

- Take some number of things and combine them in order into a larger thing.

- Take said things and link (relate) one to the next throughout.

To create a tree, we can either:

- Combine the children of one thing together in their parent.

- Relate individually the children to their parent.

To create a table, we can either:

- Use a set of lists, each combining the contents either of a row or a column.

- Link from each item in the table, relating each item to no more than two neighbors in its row an in its column

To create a graph or hypergraph: we do whatever we like.

In the thought-shaped era, we’ll be able, interoperably, to create, store, share and retrieve information shaped in any of the above ways. To put it crudely:

- Text editors allow you to work with linear information

- File browsers allow you to work with hierarchical information

- Spreadsheets allow you to work with tabular information

What comes next? How should we create graph/hypergraph-shaped information? Or seamlessly combine all the aforementioned types of information in any way we please? A robust, global, interoperable system for this purpose is the missing-link between our world and the thought-shaped world.

COEUS is our proposal for this app.

The thought-shaped word processor

COEUS is, among other things, a thought-shaped word processor. Read more about this in my article on the subject. Here are some important aspects of the design:

- Every consistent idea of literature exists in COEUS. When something is thought-shaped, it needs to have a feature/function for every concept in the human system that it’s modeling. A word processor models literature, but no word processor models aspects of language like sentences, clauses, and words (and their components). COEUS does: every sentence, say, is uniquely identified, can be moved around and referenced as a unit.

- COEUS can do relationships. For instance, I can think about the relationship between a given paragraph in one article and a word in another: the closest thing we have to modeling this in modern word processors/Web editors is what we term euphemistically a “hyperlink,” but which is innately flawed in that it is not visible when you’re looking at the thing it points to. COEUS’ links are visible from every endpoint they connect, and are visualized as lines on screen.

- “big picture”COEUS lets you point to anything you like and retrieve anything you like. As mentioned in point 1, everything that is real in literature is real in COEUS: this means that I can link to a single sentence in an article (not just the whole article). For that matter, if I want to edit a single paragraph or heading from a book, with COEUS I can open and work with that, just that, and nothing else.

Two paths: more alienation, or liberation at last from the restrictions in media that held back our thinking

AI and its purveyors come to you with a false prospectus. They claim to bring clarity, organizing information and explaining it in your own language. In fact, they are a jolly coat of paint on top of a rotting structure, which will further decay with our eyes averted and focused on the AI sitting on top.

AI does nothing to help:

- Our systems actually work together.

- Us actually to own/control our data and information, rather than having supercorporations do so.

- Us make our software more capable of actually expressing important human information rather than what comes easily to computers (tables and hierarchies).

We need, urgently, to build a better future. We must avoid the same sort of sleight of hand that gave us the thing-shaped era: we needed systems that allow us to express our ideas and expand our intellects; this means systems capable of expressing any idea, richly interlinking material, collaborating, versioning and reusing our writing.

What did they give us? Fonts, flashing lights, and print-preview.

This is all to say — leaning on Back to the Future — that we the users have the power to choose which timeline we go down: the good timeline, or the Biff timeline. The decisions we make now will determine how we think about information and by extension how we experience reality.

Of course, when you start this sort of talk, people say:

- “Users don’t care about that, they just want things to be easy.”

- “That’s too different from what they’re used to!”

- “Be realistic.”

But people before me have proved this perspective wrong again and again:

- They said all computers should be colossal and expensive like IBM’s, DEC proved them wrong by making computers for a few thousand dollars.

- They said computers were the domain only of extremely technical people, and Apple proved them wrong by creating the Mac.

- They said all operating systems should be closed and proprietary like Microsoft, and Linus Torvalds proved them wrong by creating Linux.

Today, they’re saying that users want a drip of AI slop, powered by a too-big-to-fail data system to horrible to face up to. I invite you, dear user, to join with me and prove them wrong.

We invite you to fill in our survey to help us find out more about what you need from your software.

- 1 Some provisos on this sort of thinking: 1. All eras are named by people, some are named better — more aligned with a related change in a preponderance of events; 2. Era-oriented thinking seems to be a trap for messianic and conspiratorial beliefs; 3. I speak of eras above only to make vivid important change in something I care about: ideas.

- 2 For instance, we can think about the interaction between two balls colliding; there provably is some sense in which the two balls held together are one object but it is fleeting and tenuous compared to the reality of the individual balls.

- 3 I use examples here because I haven’t found a way to distinguish relation and combination: for instance, what does it mean to combine two paragraphs to make a larger section of text other than “setting them by one another, so as to take a view of them at once” which is precisely how Kant described relation; Kant clarifies that this happens “without uniting them into one,” and I’m not sure what this means. Specifically, if I set two things together, they are necessarily united into one larger thing; this is especially true in the case of links in my system, HSM, which are uniquely identified, persistent, first class objects, which literally unite however many other things they link (text, media, other links) into one new thing. I would go further than Kant, therefore, and say that the difference between combination and relation is more a question of feel: but is no less valid, nonetheless.

We are entering the era of thought-shaped software was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More