It’s not you: your UX design job is frustrating and unfulfilling

Marx’s concept of alienation applied to today’s design industry

UX jobs are well-compensated and prestigious. They are often advertised as creative, empowering, and impactful. However, is working for Apple, Uber, or Revolut beneficial only for financial gain and career advancement, or does it also provide genuine fulfilment?

This article will investigate the labour conditions of UX designers, through Marx’s concept of alienation. I will claim that performance metrics, specialisation, and Agile frameworks limit UX designers.

This text will explore how Agile oversight can reduce the designer’s autonomy, creativity, and impact. This results in stress, a lack of empowerment, a lack of artistic fulfilment, and separation from our human essence.

Designers are the tech workers closest to the end-user. Still, because of Agile’s organisational structure, we do not have enough impact to ensure products are aligned with human interests and ethical standards.

Some scholars and industry leaders claim designers should be responsible for the ethics of their products. This claim is naive and lacks a deeper understanding of our corporate reality.

This is certainly not a feel-good article. Every designer’s context is unique, and many designers are happy in their roles. My intention is not to be a downer, but I hope my article triggers some reflection.

Sidenote:

Karl Marx is often taken out of context. His work is full of complex ideas. He looked closely at how work, money, and power shape people’s lives. His views changed over time. I personally far from agree with parts of Marx’s thoughts, but the way he is caricatured by free-market evengalists is disonhest. I hope this article shows that his thoughts can illustrate it’s worth looking at his philosophies (yes, plural).

Marx and alienation

Karl Marx’s idea of alienation helps us understand how workers feel and relate to their jobs. Alienation was not just about work, but a general problem in society, described by other philosophers.

“[Alienation is a] psychological or social ill; namely, one involving a problematic separation between a self and other that belong together.”— source

Alienation causes separation between a person and their human nature. This can happen through God, economics, politics, or property ownership. These institutions cause humans to behave inconsistently with their intrinsic essence.

Marx looked at alienation through a capitalist lens. He laid out his idea of workplace alienation in the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844. All quotes in this text are from this work, unless mentioned otherwise. Marx developed his ideas of alienation at later stages of his writings. To keep this text manageable, I will limit myself to his initial ideas.

For Marx, the worker as a person is alienated from his work. In a capitalist system, the labour the worker carries out becomes an entity on its own.

“Labor exists outside of [the worker], independently, as something alien to him, and that it becomes a power on its own confronting him.”

Note: all quotes in this text are from Marx’s ‘Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844,’ unless mentioned otherwise.

Marx explains this further in Wage Labor and Capital. He notes that workers work only for their salary, not for the product itself, or for personal fulfilment.

“The product of [the worker’s] activity … is not the aim of his activity. What he produces for himself is not the silk that he weaves. … What he produces for himself is wages.”

Alienation begins when a portion of a worker’s labour is dedicated to exchange. Labour itself becomes the product. This way, workers reject themselves as human being, leading to emotional and physical pain.

“[The worker] does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind.”

Work thus becomes an obligation and a chore, instead of an extension of one’s essence. People work out of necessity rather than desire. The very activity of labour does not give innate satisfaction. People are not themselves at work but become a worker, alienated from their human nature.

Marx identifies four ways in which someone is alienated in a capitalist society. The worker is alienated from:

- The product they create — leading to no influence over and no understanding of the end-product;

- The method of production — leading to a lack of job satisfaction;

- Their own humanity — leading to a loss of potential;

- Colleagues — leading to workplace competition and apathy.

All these forms of alienation result in a loss of self-determination and the ability to control one’s life. The worker can’t live according to their nature and desires.

1. Alienated from the product

Before the Industrial Revolution, craftsmen had complete control over their products. Products were truly their products. These craftsmen would grow kettles, build houses, or create tools and would manage the entire strategy, development, and sales process.

Under capitalism, workers became part of a system where they were only responsible for a small aspect of the production process. The division of labour. The worker would be distanced (or alienated) from the product.

Workers not only became responsible for just a part of the product, but they also lost control over its design. Craftsmen stopped creating their own products and started making products for someone else: the capitalist.

Simply making chair legs results in someone forgetting the whole sitting experience of a chair. As the production process becomes more specialised, the scope of the worker decreases, leading to greater alienation.

“The more diverse production becomes, … on the one hand, and the more one-sided the activities of the producer become, on the other hand, the more does his labour fall into the category of labour to earn a living.”

Workers who produce parts of products that they will never be able to buy or use themselves can feel even more alienated. Someone might put wheels on a Mazeratti, but might never know what it’s like to drive such a car.

A worker loses the sense of the product’s use value because the product is no longer fully understood. Consequently, the value of the work activity might also be reduced. The worker no longer cares about the product, only about the salary.

“I am indifferent to my product, being motivated instead by the incentive. To that extent, I will likewise be indifferent to the fact that my product happens to satisfy another’s need: the satisfaction of another’s need is not what motivates me.”

The maturisation of the tech industry

In the tech world, we can also see the trend from a worker fully owning the product to being only responsible for a small aspect of it.

In the ’90s, wizzkids created unique websites and other products (browsers, plugins, stand-alone chat, or peer-to-peer software).

When the internet matured and technological possibilities increased, websites became more complex. Social media and user-generated content platforms emerged, and the introduction of the smartphone created the app market. This, together with the dot-com bubble, led to the exponential growth of tech companies.

The famous Silicon Valley garage companies moved to big offices. The products became too complex to be managed by a few people, so they were split up into multiple sub-products. Many programmers were recruited to work on a specific part of these products. This trend has continued until now.

Big tech companies employ large numbers of product designers. The irony is that designers usually don’t design products; they are responsible for a very small part of them.

A designer for YouTube might be responsible for the search bar, the comments section, or the upload function. Someone in a similar role for an ERP system like SAP, Visma, or Microsoft Dynamics might work on a specific supply chain module, an email campaign feature, or the fonts or colour palette used across the ERP.

Similar to a craftsman who focuses solely on a chair leg, a digital designer might concentrate on a single aspect of their product, potentially losing sight of the overall user experience.

The designer’s lack of understanding of the product is amplified by the way the product owners assign tasks. Most companies in Agile mode rely heavily on performance metrics, which means that tasks are based on measurable outcomes.

A designer won’t be tasked with designing an unsubscribe function, but rather something more specific, like: ‘Currently, 10% of our users unsubscribe each year. Our goal is to reduce this to 5%.’

It would then be up to the designer and their team to decide whether to make it more difficult to unsubscribe or find ways to convince the user to stay. By focusing only on a small aspect of the system, the designer becomes alienated from the overall product experience.

The internet revolution also resulted in a digital environment where products are no longer stand-alone entities but part of a big ecosystem. Thus, product teams have to deal with forces outside of their own product and company.

An app has to be listed in the app store and is, therefore, obliged to follow specific design guidelines. Apps also use external payment providers (Paypal, Stripe, iDeal), login features (Facebook, Google), data-processing systems (Tableau, Power BI), front-end libraries (Material design, Ant), and user behaviour capturing tools (Google Analytics, Hotjar, Useberry), all of which have additional requirements. Therefore, another layer of a lack of control over the product is added.

Another issue in an Agile environment is that designers can spend more time interviewing the people who give them the assignments (customers) than the users (clients).

“When integrating UX methods in Agile, companies risk focusing more on customers than users.” — Source

Companies might organise planning or knowledge-sharing events to help teams understand what other teams are working on, but this is not enough to reduce alienation.

2. Alienated from the labour process

In pre-capitalist times, the worker could choose which tools to use, when to work, and decide the order of tasks. The introduction of the assembly line ended this freedom.

Flexibility is essential for an independent worker. Making quick decisions based on daily experiences is a key part of the work process.

Fatigue, inspiration, family situations, and seasons influence the worker’s day. In a capitalist society, labour becomes monotonous and repetitive because the tasks of a single worker influence the other workers and the production cycle.

“Individual craftsmen (and, to a lesser extent, women) had a degree of control over their work and could take pride in what they produced, under capitalism, work simply becomes a chore.”

Labour automation makes people operate like robots, or in Marx’s words, animals. If someone can’t control their own actions, they are not free.

“Freedom is autonomy, where an activity is (fully) autonomous if and only if it is an unqualified expression of its agent’s will. In particular, it is autonomous only if it is an expression of her will rather than someone else’s.”

The harmonisation of design

The maturation of the tech industry also required harmonising design and development methods and making workers less flexible and impulsive.

The 1990s webmasters handled the system’s graphic design, functional design, and backend coding themselves. They didn’t follow design tool conventions, UI interaction patterns, or programming guidelines. The independent tech worker was reasonably free in making choices. The main restrictions arose from global technical constraints, such as internet speed and the limitations of HTML and coding languages.

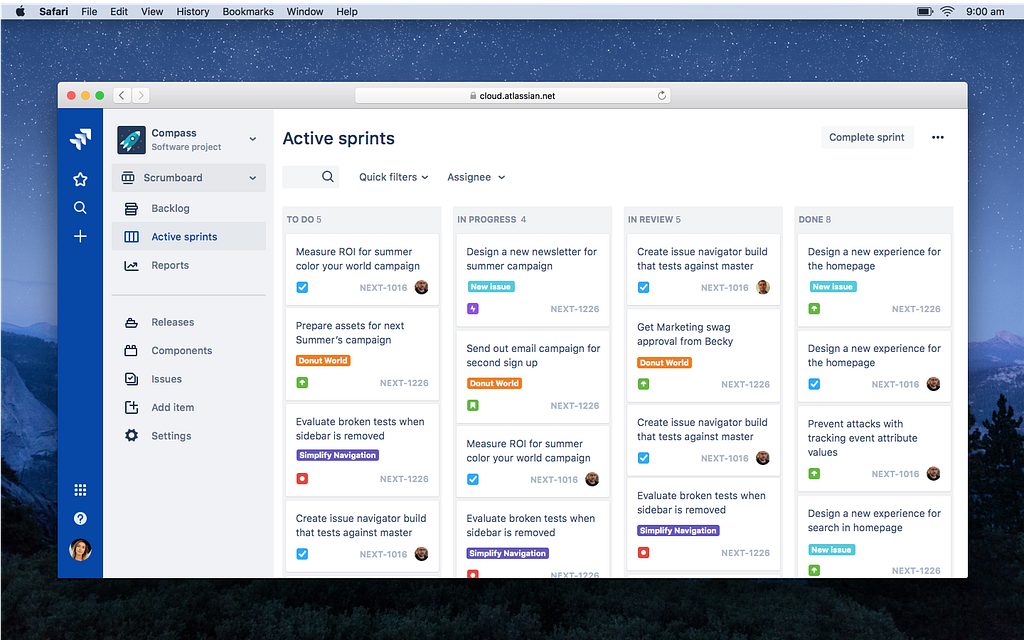

Today, mature Agile organisations dictate how designers work. Companies define the software (Figma, Adobe XD) that a designer must use and how the tool needs to be utilised (name your symbols!). This harmonisation is required for a smooth handover between designers and programmers.

Following industry standards can be exceptionally valuable to designers because it makes them more hireable by other companies.

Something that causes huge frustration among designers and engineers is the mandatory Agile ceremonies.

In a 2-week sprint, designers often have a sprint planning, a sprint review, a backlock grooming session, and a retrospective. This is of course in addition to daily stand-ups.

Likewise, designers might have co-designing sessions or design critique meetings. In addition to these regular meetings, planned for every sprint, designers might have meetings with their customers and users and may attend or host workshops.

This overload of meetings not only frustrates the designer but also compromises design work.

“Professionals seldom pick a UX method not fitting into a Sprint. These strict deadlines make it impossible to follow an open approach that can be reiterated until enough information is gathered as in qualitative research, reducing the UX method’s quality.” — source

UX Designers often describe themselves as introverted, impulsive people. I am personally absolutely one of them. Simply surviving the workweek with an abundance of meetings can be challenging. It might make it difficult to have any energy left for what a designer considers the core of their work: designing.

The worker has lost complete control over their schedule and choices.

“Some teams may feel a lack of autonomy when certain decisions … could not be made by themselves. … The teams did not have freedom to choose which features to build. They had been decided in pre-planning meetings.”— source

The UX designer doesn’t have control over their workday. The UX designer is alienated from the labour process.

3. Alienated from one’s own humanity

Marx also recognises the disconnection from one’s human nature as a distinct form of alienation.

When people follow their human nature, they want to develop their creativity and productivity. The old craftsman was always focused on innovation and improvement, both in himself and his product. Yet, in a capitalist world, work became a commodity that can be bought and sold. A worker thus lost a sense of his own abilities, of his spiritual essence.

The worker no longer pursues their natural impulses but simply follows the tasks assigned by the capitalist. As a result, a person can lose their sense of identity and may feel disconnected from themselves.

“The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself.”

Designers are experiment preparers

The word design implies creativity, freedom, and exploration. The role of UX design is often misunderstood and differs greatly from people’s typical associations with design. Many designers have enormous potential. However, their roles and the sub-products they work on are so small that there is little room to utilise the very skillset they desire to grow.

A designer needs to stay in their team’s lane and usually follow the company’s design system. These systems define the artistic, structural, and linguistic criteria that all the company’s output must follow. A designer can exclusively pick from a set of given components to build a UI, similar to assembling an Ikea kitchen.

A designer for McDonald’s can’t suddenly use pink or purple in their app. A designer for a news website shouldn’t distort the visual grid of news articles and ads. A designer for a tax declaration system shouldn’t use jolly language. The design system must be respected.

Creativity is even more compromised in recent years because design tools use AI to support the designer in optimising their layout. When a designer tries to propose something artistic, design critique meetings, customer feedback, or user testing data can quickly end this creative endeavour.

Data, in particular, makes the design process more of an empirical science than a creative enterprise. Most companies are data-driven. Every change applied to products is deeply analysed. Short experiments with minor changes are continually executed to measure the potential behavioural change a new element might yield. Two variations of one button might be shown to a pool of people, and the best-performing option will be permanently implemented.

Thus, designers essentially become experiment preparers. They need to follow the design system, justify their choices in meetings, and consequently test the impact of their proposal through user data.

The designer is deprived of their creativity and potential and alienated from their humanity, or as Marx would call it, Species-Being.

4. Alienated from people

“An immediate consequence of the fact that man is estranged from the product of his labor, from his life-activity, from his species being is the estrangement of man from man.”

The three forms of alienation discussed before, alienation from (1) the product, (2) the labour process, and (3) human nature, lead to the fourth and final form: the alienation from other workers.

Labour is turned into a commodity. Someone’s hard work is treated as a product with a monetary and measurable value. You have a salary and deliver a certain number of tasks. This results in competition between workers. Work revolves around which employees produce the best quality and quantity for their employer. Hence, which worker’s product, service, or commodity is most valuable to the capitalist?

For Marx, human nature is social and collaborative. Competition in the workplace, created by putting monetary value on labour, takes away this essence. People are reduced to quantifiable entities.

The commoditisation of labour not only leads to separation between workers but also to a distorted relationship between worker and employer. The relationship between boss and employee becomes transactional and toxic.

The worker becomes distanced from his social nature and becomes apathetic to his social environment.

“The worker’s role is determined by social needs which … are alien to him.”

Work becomes a meaningless exercise for the worker to keep themselves and their family alive.

“The maintenance of his individual existence appears to be the purpose of his activity.”

The gamification of work

Agile’s demand to make everything measurable targets not only the product but also the internal organisation and the performance of every team. Think about work estimation through story points. Story points are simply a currency used to quantify a task’s workload. Story points enable teams to track whether they perform well in relation to their previous sprint cycles.

In ‘good’ Agile, individuals should not be responsible for specific tasks and their story points; this should be the responsibility of the entire team. Yet, in reality, team members are assigned tasks and compare their output with that of their teammates. In addition, in many teams, certain individuals have specialisations that only they can carry out.

Companies often don’t employ enough designers to have one or more in every team, further alienating the designer from their colleagues:

“The designers and developers complained about a lack of regular communication where they felt that [design] work and software development was often not aligned and they did not feel part of the same team.” — source

Consultancy firms also encourage companies to implement gamification methods, setting teams up against each other through leaderboards. Performance metrics become a way to compare and shame fellow colleagues.

Remote work, digital feedback and communication systems, and asynchronous work possibilities also lead to colleagues spending much less face-to-face time with each other.

Short-term contracts, specialists recruited through staffing agencies, and offshore teams are common in the tech industry.

“In effect, [these second-class employers] become an internalised reserve army of labour …. These developments create competition between professionals, insecurity, frustration, friction and conflict, and encourage a blame culture.” — source

The product designer indeed gets alienated from his peers through gamification, feedback sessions, measurable performance, and a tiered contract structure. This is despite the intrinsic mechanisms Agile has in place that ought to bring teams together.

5. Alienated from home and family

Marx describes the 4 types of alienation listed above. Yet, I argue there is a 5th form of alienation at play in today’s tech landscape: alienation from home and the family.

Companies offer free lunches, snacks, and (strategically scheduled) late dinners, on-campus gyms and yoga lessons, massage sessions, ping pong tables, and a whole array of other forms of entertainment.

Some corporations offer services such as laundry, childcare, and commuting assistance, including onboard Wi-Fi, so employees can start working instantly when leaving their homes. In addition, frequent team-building events, after-office-hour drinks, workstations, and socially responsible initiatives like blood donations, charity runs, and beach cleaning days are organised.

Companies implement ways to nudge workers into feeling less at home physically and emotionally, making work a more significant part of their identity. Lanyards, baseball caps, T-shirts, and other company merchandise are also distributed to give the worker a sense of belonging.

Firms want their workers to associate themselves primarily with their jobs, not their family or social community. Companies institute tribalistic titles for their employees: Facebook employees are called Metamates, Reddit staff are known as Snoos, the Spotify team is called ‘the band’, and Salesforce employees are Ohana (a Hawaiian word meaning family).

So, who is your family? Who do you identify with? Who do you spend more time with? What do you think about when you can’t fall asleep? What is the most satisfying achievement you had recently?

Is your primary identity related to your personality or profession? What do you answer when someone asks you who you are?

Why does alienation matter?

For Marx, alienation is damaging because it undermines human flourishing. Alienation takes away what it means to be human: social, creative, and self-actualising.

Labour shouldn’t be only a way to survive but a form of self-expression, allowing the worker to realise one’s species-being.

Like the 19th-century factory worker, today’s UX designer is deprived of their human essence. I argue that the contrast between how companies advertise their design roles as empowering, creative, and fulfilling, and the genuine reality, causes cognitive dissonance among designers.

Designers are the tech workers who experience the highest rate of burnout. Design leadership author Peter Merholz concludes that designers’ lack of belonging in a team of engineers (alienation from the worker) and unrealistic workload (alienation from the production process) are the leading causes of stress.

I believe that a lack of artistic fulfilment (alienation from one’s potential) contributes significantly to the designer burnout rate. Furthermore, the compassionate nature of designers is another cause for mental friction.

Designers are often motivated to improve the lives of the end-users and humanity more broadly, but their limited product scope can lead to a sense of disempowerment. When a social purpose is reduced to business performance metrics, human nature is constrained.

Designers are also systemically treated as a pooling consultants, serving multiple teams, rather than being embedded in a single team.

“Developers were usually co-located in one designated team, whereas designers were often required to move between different teams and projects.”— source

Designers feel alienated, even more than software engineers, because most tech companies are engineer-led. Designers are treated as second-class citizens, with increased burnout rates and corporate cynicism at risk.

Designers are losing their human essence, as they cannot be social, creative, or self-actualising. Designers are also unable to help the users they want to design for. This is why alienation can’t be ignored.

Conclusion

Designers often work on small sub-products and are subject to company-wide design guidelines. The Agile process dictates how designers should behave on an hourly level.

Product performance metrics, user data, and design critiques limit designers’ creative potential. Agile performance metrics, applied to the team and individual, make the designer a mechanical link in Agile delivery rather than a human with autonomy.

Marx’s theory shows how designers are alienated from the product they create, their work process, their human essence, their colleagues, and even their family lives.

Companies might not consciously intend to alienate their staff through Agile frameworks. Still, alienation is the logical result of:

- The expansion of the tech world,

- Increased complexity of digital products,

- Industry professionalisation,

- Investor pressure.

Designers may begin their careers believing that they will spend most of their time in design tools exploring creative boundaries while crafting app screens, animations, and icons. However, sub-products, performance metrics, design systems, and agile ceremonies often leave little room for self-expression.

Comparing today’s work to Marx’s concept of alienation is not just a philosophical exercise. It shows how even in highly desirable sectors, human needs for purpose, freedom, and belonging are unfulfilled.

Marx’s insights from the 19th century continue to be applicable in today’s workplace. The dot-comrades lost their agency. We lost our agency. If we want to bring it back, the first step would be to acknowledge our alienation. This article aims to create this awareness.

It’s not you: your UX design job is frustrating and unfulfilling was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More