Enhance UX research with deconstruction

Why our best design work begins only after we’ve questioned what we think we know.

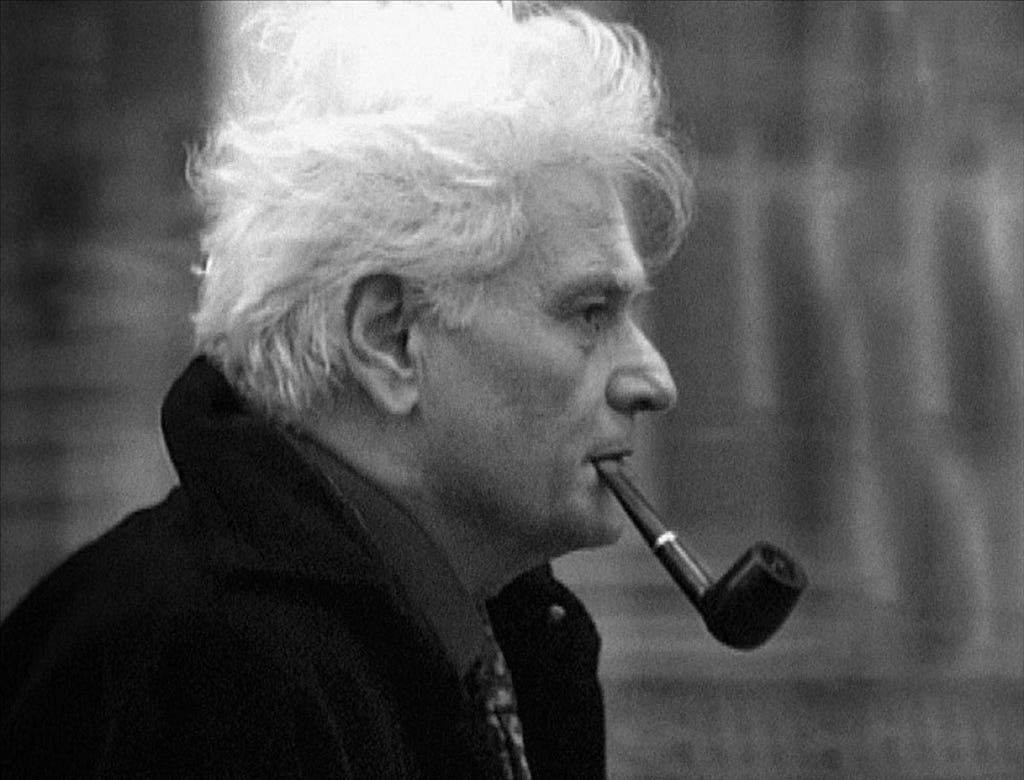

Deconstruction, introduced by French-Algerian philosopher Jacques Derrida (1930–2004), can be understood as the practice of critically examining how meaning is constructed by dismantling the hidden assumptions, hierarchies, and contradictions in the structures we use to make sense of the world.

A key move in Derrida’s work is analyzing binary oppositions in language and writing — simple/complex, usable/unusable, good/bad — where one side is treated as superior. These pairs define each other—“simple” only makes sense in contrast to “complex,” and “intuitive” exists only because we can imagine the “non-intuitive.” Reversing them reveals how the favored term depends on the one it rejects.

In UX, research insights hold a weight similar to the binary constructs central to deconstruction. They’re the currency of design — winning stakeholder approval, shaping roadmaps, and often becoming the “truth” teams rally around. But no matter how rigorous the process, insights aren’t pure—they are shaped by the questions we ask, the patterns we notice, the logic we apply, and the biases we overlook

This is where Derrida’s approach can be systematically applied to UX. Just as he dismantled the stability of meaning in the frameworks we use to understand the world, we can dismantle the illusion of objectivity in research.

The simplicity mirage

Consider the finding — “Users prefer a cleaner, simpler dashboard with fewer widgets.” In a traditional analysis, the assumption might mean less clutter equals better UX—so the obvious step is to remove widgets.

However, in a deconstructive analysis, you first recognize the binary at play — simple versus complex — and then question a hidden assumption driving it — that complexity increases cognitive load.

You might ask whether some complexity could actually reduce effort, the way a weather app showing both temperature and humidity at a glance saves the user from digging deeper.

You might also consider cultural bias — that the “clean” aesthetic mirrors dominant tech brands like Apple and Google — and whether users are responding to genuine usability or the comfort of familiarity.

Instead of ripping out widgets, one could explore ways to make them more useful or accessible — even if that means breaking from the familiar “clean” look.

The intuitive trap

Just as “simple” and “complex” can hide bias assumptions, so can other common UX judgments. One of the most misleading is “intuitive.”

Take a finding like, “Users found the swipe gesture more intuitive than the button.” The traditional move might be to replace the button with the swipe. A deconstructive approach asks whether “intuitive” actually means anything beyond “I’ve seen this before.” It recognizes that so-called intuition often comes from muscle memory, not innate understanding, and that this memory is culturally and temporally bound.

Derrida would point out that “intuitive” only exists in contrast to “non-intuitive,” and that these definitions shift over time. In practice, this could mean recognizing that while a swipe may feel natural to some, it could alienate others unfamiliar with the pattern.

A better solution might be to offer both, or to design onboarding that transforms the learned into the intuitive.

The persona archetype

Personas are meant to focus design yet they can quietly embed hierarchies. A common example might be “Our primary user is a 34-year-old professional woman who shops online twice a week.” The category of “primary” only exists because there are “secondary” or “non-users” to define it against.

Deconstruction asks what happens when you flip that pair. If the so-called secondary users — those at the margins — become the baseline, it exposes how “primary” is often just a reflection of business priorities or cultural defaults. That shift can force a complete rethinking of the product’s design language, features, and underlying assumptions.

Turning insight into interrogation

Deconstruction reframes an insight as a starting point, not an endpoint — every research output carries binaries, privileges, and assumptions, whether we acknowledge them or not.

However, as fascinating as this idea is, you may be wondering how to actually use it. Here’s the method and an example in practice.

The Method

- Identify the binary: Start with paired concepts where one side is privileged over the other — such as simple/complex, primary/secondary, intuitive/non-intuitive, or one feature/channel vs. another.

- Interrogate the hierarchy: Flip the priority and ask what changes if the “lesser” side becomes the favored one.

- Expose the scaffolding: Uncover the assumptions, beliefs, and contextual factors that support the favored side — cultural familiarity, business priorities, personal preferences.

- Hold both in play: Resist replacing one side with the other. Instead, design so both can be valid depending on context, recognizing that meaning emerges in relation and cannot be fixed.

Example in Practice

Let’s apply these steps to a real finding: “Users prefer live chat over email support.”

- Identify the binary: Live chat vs. email support — live chat is framed as fast and responsive, privileged over email, which is seen as slower and more formal.

- Interrogate the hierarchy: Flip the priority. What if email were the preferred option? Who benefits in that world, and what needs would it serve better?

- Expose the scaffolding: The assumption behind the original finding is that real-time communication is inherently better. But maybe older users find chat overwhelming, or certain cultures value the formality, permanence, and asynchronous nature of email.

- Hold both in play: Keep live chat for speed, but also enhance email with templates, clear response times, and integration into the same support flow — treating both as valid depending on context.

By following these steps, you surface hidden dynamics and expand your design options, rather than narrowing them to the favored side of the binary.

Why this matters

Research culture loves certainty. Insights are presented in slide decks as if they’ve been carved into stone, free from the messiness that produced them. But that messiness is where the pivotal design opportunities live.

By applying deconstruction, we resist the urge to turn research into gospel. We stop treating the discovery phase as a vending machine — insert method, retrieve truth — and start treating it as an ongoing dialogue between our users, our products, and the contradictory worlds they inhabit.

A philosophical closing

Derrida wasn’t trying to make things easier to understand — he was working to expand what meaning could be. That ambiguity is a gift to UX because it pushes us to question the hierarchies and assumptions built into our design language and research interpretations.

When we stop treating an insight as the final word, we create space for design decisions that are more thoughtful, more adaptable, and ultimately more human.

Don’t miss out! Join my email list and receive the latest content.

Enhance UX research with deconstruction was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More