In 1949, he said you’d be addicted to your phone

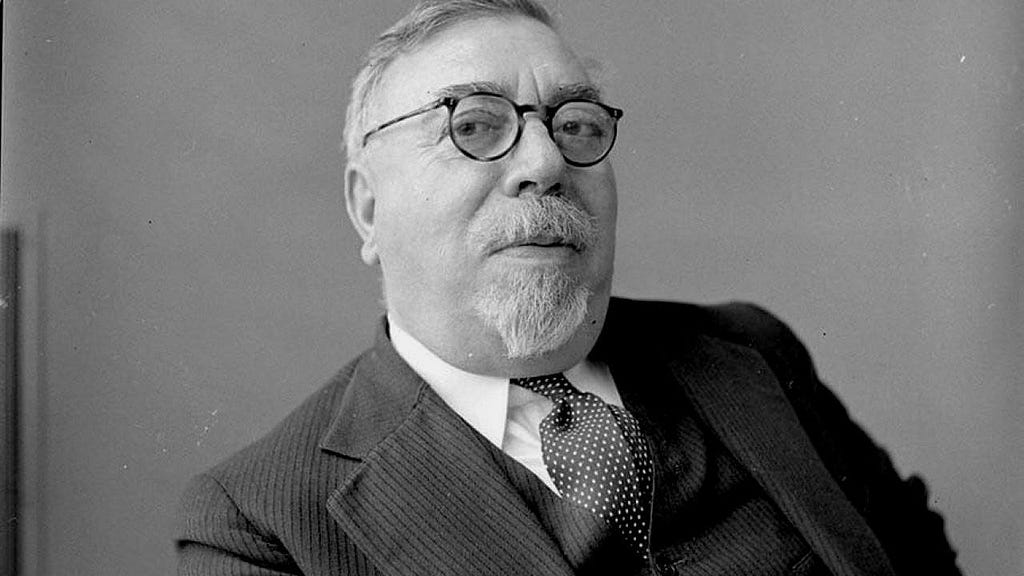

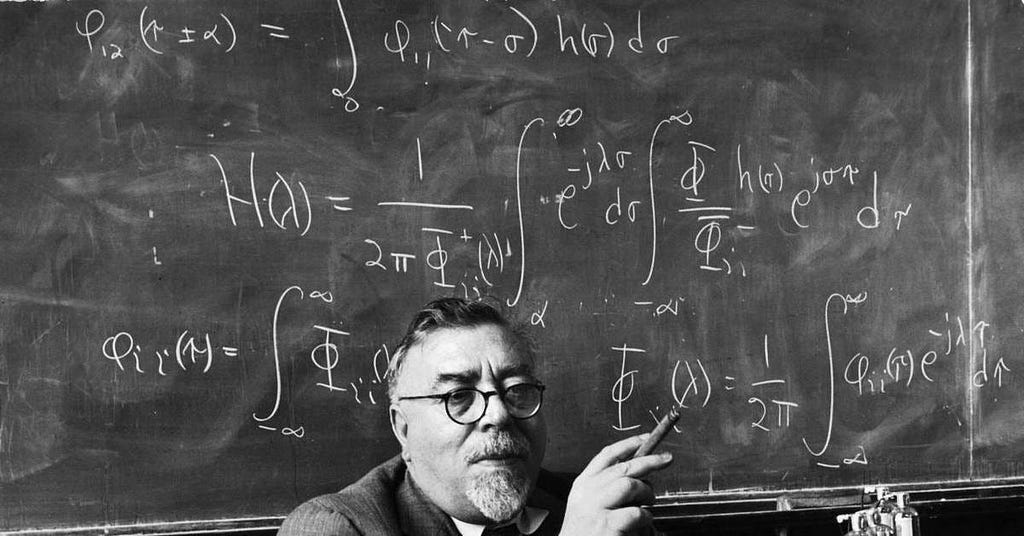

Norbert Wiener, cybernetics, and the feedback loops that still run our lives.

It’s late and you’re still scrolling.

A guy at MIT explained why this would happen — in 1949.

One more swipe, one more refresh.

I’m Nate Sowder, and this is installment five of unquoted… a series about the people behind the ideas we can’t afford to forget.

Edited by Pat Hoffmann.

In the 1940’s, nobody was talking about “screen time.” Yet Norbert Wiener was already studying the forces that would later fuel parental bargaining and childhood meltdowns. He called it cybernetics: the science of control and communication across both machines and people.

This idea was born out of World War II, when Wiener worked on antiaircraft systems designed to predict and adjust to the movements of enemy pilots. The guns learned where you were going and got more accurate with each shot.

It’s the same principle that keeps you glued to your phone. A loop that tracks what you do, feeds it back into the system, and adapts to keep you coming back.

Wiener saw the power… and the danger.

A brief history

Wiener was a mathematician and philosopher who spent the war years at MIT, building what we now call predictive systems. His key insight was pretty simple: if a system uses the result of its last action to guide the next one, it can adapt. He called this a feedback loop.

In 1948, Wiener released Cybernetics. Two years later came The Human Use of Human Beings. Together, they introduced a new science — and a warning: adaptive systems would change human life faster than society could handle.

Wiener knew three things

Wiener’s ideas can be distilled into three truths.

Metrics become reality.

A thermostat doesn’t “care” about the weather outside… it just enforces the comfort range you set indoors. A fitness tracker doesn’t care about health… it rewards steps, because that’s the metric it’s built to count. A social feed doesn’t care about truth or insight — it rewards whatever keeps your eyes on the screen. The loop always chases the goal it’s given, and that goal is never random. It’s the designer’s definition of success, baked in from the start.

Speed shapes your control.

During World War II, fire-control systems had to predict the position of an enemy plane seconds into the future. The faster the loop, the more accurate the shot. Today, the loops on our phones close in milliseconds and anticipate us before we even notice.

Every system is a moral system.

Every goal comes with a tradeoff. A navigation app that shaves two minutes off your drive but routes you through a neighborhood. A hiring algorithm that favors speed over fairness. A social feed that rewards outrage because it generates clicks. None of these are neutral, and each reflects what the designer (or the business behind it) decided was worth maximizing.

Metrics become reality

Every time you refresh a feed, a loop is closing. Your action becomes data. The data shapes output. The output shapes your next action. The loop is invisible, but it’s always deciding what gets rewarded.

When Wiener warned about this, he wasn’t imagining TikTok. He was looking at factory automation, early computing, and machines built to optimize whatever they were told to measure. “The automatic machine,” he wrote, “is the precise economic equivalent of slave labor” — productive, tireless, and indifferent to human costs.

Design today runs on the same principle. If the loop rewards clicks, you get clickbait. If it rewards time spent, you get infinite scroll. The loop doesn’t invent the goal, but it enforces the one it was given until it shapes behavior around it.

Speed shapes your control

Wiener’s deeper concern wasn’t just what loops measured, but how quickly they could run.

A feedback loop is powerful because it learns. But when it learns faster than people can think, it stops being a tool and starts being a trap. In wartime, that speed meant predicting a pilot’s move before he could make it. In consumer tech, it means shaping your behavior before you notice it happening.

That line could be dropped directly into today’s AI debates. Systems that adjust in milliseconds leave no room for pause, doubt, or deliberation. The loop has already chosen, and most simply follow its lead.

Every system is a moral system

This is more of an ethical directive than a metaphor. Adaptive systems decide which problems get solved. They decide where attention, time, and reward are distributed, giving more to some and taking away from others.

Wiener wasn’t drafting policy, but he was pointing straight at what we now call AI ethics. Systems aren’t neutral. They carry values in what they measure, who they serve and who they leave out. The arguments about bias, accountability, and control aren’t new… they’re echoes of what he was already warning.

Designers love to talk about usability, functionality and accessibility. Weiner cut through all of it by stating that every system is a moral system. If you don’t name the strategy you’re going after, the loop will. And the loop always sides with whoever built it.

Why it matters now

Wiener’s books came out before most people even owned a television. Yet his warnings read like commentary on today: automation moving faster than people can adapt, algorithms optimizing the wrong things, systems shaping behavior behind the scenes and in ways we can’t reverse.

Wiener was pointing out something important: in an automated world, feedback loops hold the power. They’re not just technical details running in the background, they decide what gets measured, who benefits and how fast things change. That’s why they sit at the center of design, AI, and strategy.

Every loop is a kind of policy. Every metric is a choice about what matters, and every system gives power to some people and takes it from others.

Wiener left us with both the science and a warning. The big question is whether to treat design and AI as more than just products… and see them as systems that shape how people live.

In 1949, he said you’d be addicted to your phone was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More