Case studies are the real product

The true power of your design comes from its story, not just its surface.

Designers at every stage — whether seasoned professionals or juniors just starting out — tend to place enormous emphasis on the final artifact. The polished app mockup. The slick responsive website. The cleverly executed logo. These artifacts feel like the fruit of our labor, and naturally, we take pride in them. A finished design is tangible. It’s something you can click, hold, or admire on a screen. It feels like proof of progress and evidence that you did something real.

But the hidden twist is that the artifact isn’t the product that matters most for a designer. The case study is.

Professional designers don’t stand on beautiful artifacts alone. We stand on evidence of thinking. The website, the app, the identity system — these are only fragments of that evidence. What gives them meaning is the story behind their creation. The reasoning. The trade-offs. The impact. And the vehicle for telling that story is the case study.

Most designers will admit that case studies are important. But too often, they still get treated as an afterthought — an appendix tacked on once the “real” work is done. The reality is that the case study isn’t just important, it’s the most important artifact you’ll ever create. It doesn’t just show what you built—it reveals how you think. And that’s what separates a decorator from a true designer.

The case study as the product

Yes, the app or website or identity is what the user interacts with. That’s important. And obviously, the primary goal of design is to create products and services that solve user needs. That’s the point of the whole field.

But here’s the distinction—the shipped artifact is the product for users. The case study is the product for your reputation.

That reputation-building side of design ties into what philosophers call psychological egoism — the idea that even when we act for others, we’re still motivated by some underlying degree of self-interest.

A case study isn’t just evidence of user-centered design — it’s also the work that advances a designer’s career. That overlap is what makes case studies powerful—they showcase real problem-solving for users while also serving as proof of value for the designer.

This reframing matters because it shifts what we aim for. If the goal is simply a polished artifact, the focus narrows to execution. But if the goal is a compelling case study, the emphasis moves to process, strategy, and outcomes. The work stops being surface polish and becomes evidence of your thinking — which is what truly matters.

Why we get it backwards

This is where design education and professional culture miss the mark. We treat case studies as something to think about only after the work is done.

In many UX bootcamps, certificate programs, and even some university tracks, case studies are typically introduced late in the curriculum. It’s positioned as a capstone—gather all your projects, polish them up, and write about them so you can get hired. The case study becomes little more than packaging.

But it should be the first thing designers learn about. Before research methods, before the design tools, even before methodologies such as Design Thinking or The Double Diamond. Because if you learn how to build a case study from the very beginning, you start to understand design not as the production of artifacts but as the weaving of a narrative that anchors your choices and process.

Think about it, if you know you’re going to have to tell the story of your project, you approach the work differently. You pay closer attention to why you’re doing what you’re doing. You make notes of trade-offs instead of glossing over them. You frame your research in terms of insights rather than just activities. You start seeing the process itself as the real craft.

When you work backward from the case study, you design with clarity. You’re not just chasing a polished app or website — you’re shaping a story that captures the essence of your journey.

Obviously, You can’t write a full case study before the work starts, but you can create its outline. Think of it like drafting a story arc — set up the sections you’ll need, then fill them in as the project unfolds. Keep notes, photos, and feedback along the way so by the end most of the story is already written.

The anatomy of a good case study

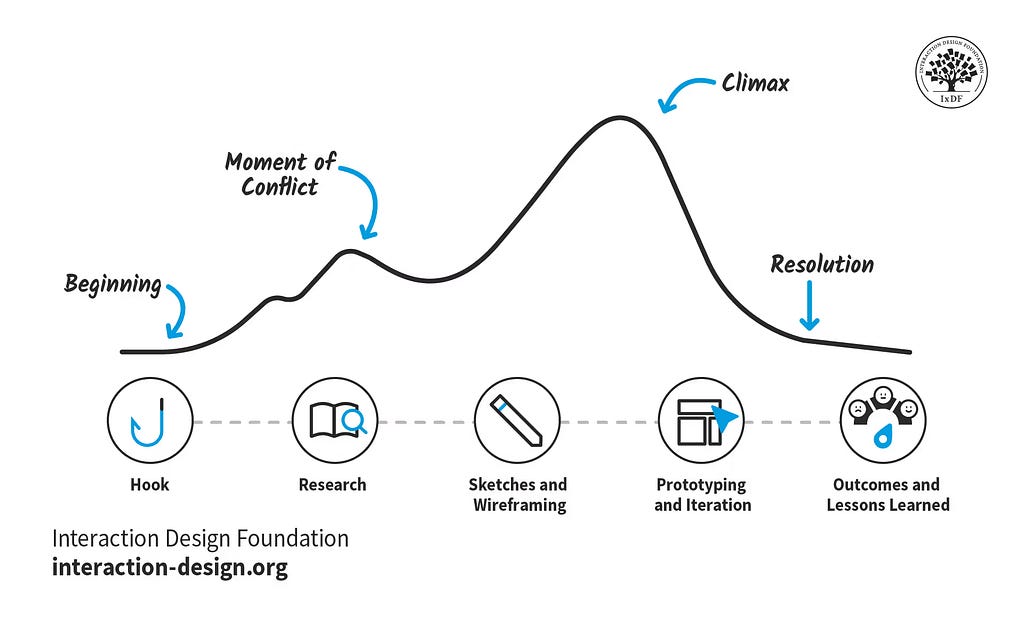

Interaction Design Foundation (IxDF) offers one of the clearest breakdowns of what a good case study should contain, and their advice matches what separates strong portfolios from forgettable ones. Because beyond structure, a good case study works like a story.

The hook is your opening frame — your role, the project type, your contribution, and a glimpse of outcomes. Think of it as the opening scene. If hiring managers don’t know what they’re looking at within seconds, they’ll move on.

Next comes research, but framed less as a list and more as the setup for conflict. Context, constraints, goals, and the “why” behind your approach establish the stakes. This is where the problem is defined, much like the tension that drives a narrative forward.

Then you move into sketches and wireframes. These are the first attempts at resolution, the early actions your “character” takes to meet the challenge. Even rough sketches show decision-making, especially when annotated. Fidelity doesn’t matter — clarity does.

Prototyping and iteration become the rising action. This is where feedback forces change, testing reveals obstacles, and you demonstrate adaptability. Show the bumps, not just the polish. That’s where resilience and growth appear.

Finally, you reach the resolution and reflection. Outcomes, lessons learned, and impact close the loop. Did your design solve the problem? Did it move the needle for users or the business? What didn’t work, and what would you do differently? Just like in storytelling, admitting flaws doesn’t weaken the arc — it makes it authentic.

A case study told this way doesn’t just show what you built. It shows how you think, how you navigate conflict, and how you grow through the process. That’s the real story hiring managers, and even you yourself, are looking for.

The frustration and the opportunity

Of course, most designers don’t like writing case studies. They’re tedious. They take time. They don’t feel as creative as pushing pixels around. And yes, hiring managers often skim.

But here’s the opportunity—if most designers treat case studies as a necessary evil, then the ones who treat them as their core craft will stand out. They show they can think at a higher level. They show they understand design as more than execution. They show they can lead, not just decorate.

And this isn’t just advice for students or juniors. Seniors benefit just as much — the scope simply shifts. A junior might focus on wireframes, while a senior might unpack an organizational strategy project. Case studies evolve with your career. But that growth only happens if you stop treating them as an afterthought and start seeing them as core to the work itself.

Designing the story

The design world loves to fetishize the final artifact. It’s shiny, it’s clickable, it’s shareable. But the deeper truth is that artifacts are disposable. The case study is what endures.

That’s why the case study is not just documentation but the real product of a designer’s work. It’s the artifact that proves your ability to think, decide, and create with intention.

If you understand how to build a case study, you understand what it takes to build a product. And if you start with the case study in mind, you’ll design with more clarity, more purpose, and more honesty.

The artifact might dazzle in the moment, but the case study carries the truth of your thinking forward. One fades with time, the other becomes the record of who you are as a designer.

Don’t miss out! Join my email list and receive the latest content.

Case studies are the real product was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More