Start with the experience

What Genie taught us about customer-centric innovation — and how those lessons still shape great products today

Long before apps and app stores, this is how a small team out-paced global giants to design one of the world’s first mobile internet portals — and shape the future of connected experiences.

In the late 1990s, the global giants of tech and telco bet billions on mobile internet architecture. We anchored ourselves to a single principle: that the future of the internet would be personal, mobile, and woven into every moment. This is the story of how our small team, Genie, out-paced those giants with $100 million less — by starting with the experience, not the platform. And crucially, we weren’t just thinking differently — we were moving faster.

Even more remarkable, Genie’s first public alpha launched as early as 1997, more than three years before Vodafone and Vivendi unveiled Vizzavi in June 2000. When it came to WAP — the technology that made mobile web experiences possible — Genie’s services went live in January 2000, a full six months before Vodafone entered the market. By the point Vizzavi was preparing for launch, Genie already had 900,000 registered users. While much of the industry was still debating what “mobile internet” meant, BT Cellnet had already shipped a working prototype — so innovative that The Guardian noted that “BT Cellnet has been an innovator and launched the mobile [WAP] version of its Genie web portal in January.” That early advantage — measured in years, not months — shaped how we approached every decision that followed.

This core conviction led to the creation of Genie, one of the UK’s first mobile internet portals. It also set us directly against the largest corporate forces in Europe. While incumbent telco giants spent hundreds of millions trying to force massive, integrated platforms onto the market — such as the Vodafone/Vivendi Vizzavi joint venture — our small team had to achieve more with roughly 1/20th of the capital.

This case study compares those two radically different innovation strategies: the Architecture-first approach of the incumbent and our Experience-first approach. It is a story about how sequencing — starting with the customer experience and working backwards to the technology — transformed an idea into market impact, and why those same lessons still define the gap between product failure and breakthrough success today.

When the internet learned to move

Having worked on some of the world’s earliest smartphone prototypes at BT Cellnet — including Nortel’s pioneering Orbitor/Europa concept — I went on to co-found Genie, the UK’s first mobile internet portal and one of the first anywhere in the world. I served as head of music, games and entertainment, receiving a BT Recognition Award as a co-founder.

This is the story of what we built, how we did it, and what it taught us about designing products and services that people genuinely want. It’s also a reflection on the choices that made the difference—the strategic calls, cultural decisions and customer-centred design principles that transformed ideas into impact.

Most importantly, it’s a story about how strategy really works when technology, experience and organisational change collide, and why those same lessons still matter for startups and product teams today.

The set-up: two very different bets on the “mobile internet”

This case study compares two radically different approaches to innovation during the first mobile-internet wave — Genie (BT Cellnet/BT) and Vizzavi (Vodafone + Vivendi) — and distils what those choices mean for two audiences:

- Early-stage startups searching for product-market fit.

- Large organisations trying to think and ship like startups.

My aim is to show, with evidence, how decisions around strategy, business-model innovation and value-proposition design can either accelerate ideas into reality, or quietly stop them from ever getting there. This is because in my role today mentoring startups, I still see the same patterns we lived through repeating themselves today.

Personal context (1996–1997)

I joined BT Cellnet in 1996 as Business Development Manager for smartphones, coming from a user-centred design and customer-experience background inside BT. Even before the word “smartphone” existed, we were already proving how mobile devices could deliver real services, not just calls and texts.

One of the most significant projects I worked on was a collaboration with Alcatel and Barclaycard on a handset that offered customers 20 % off their call costs and included a dedicated “B” button to check credit card balances, all powered by over-the-air menu updates (SOAP). The strength of the idea lay in its simplicity, and usability was intentionally built in from the beginning. My role was to help shape the vision into something tangible: defining the user experience, scoping how the service would work, and building the partnerships needed to bring it to life. That experience deeply shaped my thinking when we went on to build Genie, showing how a clear value proposition and seamless experience could change customer behaviour at scale.

By 1997 we were already building client–server mobile services. BT Cellnet was among the most innovative operators in Europe at the time, and handset manufacturers selected us as their development-partner network, giving our small team hands-on experience with device–service integration long before it was mainstream.

Even at this early stage, we were exploring bold visions of what a connected, mobile future might look like. As Business Development Manager for smartphones, my role was to identify these emerging opportunities and translate them into real partnerships, prototypes and product concepts.

That background gave us an edge over Vodafone. We treated design as strategy, embedding user experience, service design and customer insight into product and partnership choices, rather than relying on traditional corporate levers like mergers, acquisitions or joint ventures. This was design thinking in its original sense: putting the customer and the end-to-end experience inside strategy, not simply layering it on top.

(For context, 1997 was also the year Steve Jobs famously contrasted Java’s “cross-platform” vision with Apple’s integrated approach — a debate that shaped how we thought about platforms and apps.)

Experience-first vs. architecture-first

Jobs also argued that you must “start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology.” That principle became our north star. We began with the end-to-end experience and the value proposition we wanted to deliver, then built the enabling stack and partnerships around it.

By contrast, Vodafone and Vivendi started with a joint-venture architecture, trying to reconcile brands, organisations, technology and content before they had a clear, validated customer experience. That difference in sequencing shaped everything that followed.

The contrast in sequencing also reflected a profound difference in risk appetite. Genie’s approach embraced the calculated risk of rapid iteration and low-cost failure — shipping simple services quickly and learning from real user behavior within the constraints of the technology. By contrast, Vizzavi chose the traditional corporate risk: massive capital outlay and structural integration before validating a clear customer value proposition. This structural difference determined not only their speed but their ultimate financial viability.

Genie’s playbook emphasised shipping services that people could actually use on 2G/WAP; making them network-agnostic to maximise audience; pricing them to encourage exploration rather than meter usage; and iterating fast with content partners. The public record shows key Genie milestones: the UK’s first free-access mobile ISP, the first commercial pre-pay WAP service, and later the UK’s first unmetered 24/7 mobile internet service for £20/month.

Vizzavi’s playbook, meanwhile, focused on building one pan-European portal and brand, backed by heavy investment and exclusive content. The joint venture ultimately cost hundreds of millions, struggled operationally (including a botched email-platform upgrade), and was folded into Vodafone live! by late 2002, having spent £500 million building the brand.

The outcomes highlight the failure of the architecture-first approach. Vizzavi focused on consolidating assets and capital, but the platform was never truly designed around solving a fundamental customer job-to-be-done. In contrast, Genie’s success proved that agile execution and genuine customer value beat billions in misaligned capital — a lesson that remains universally true for any startup facing large incumbents.

What a mobile internet portal was (and where WAP fits)

In the late 1990s, a “portal” meant a curated front door to online services. AOL and CompuServe served as dial-up destinations on PCs — but there was no equivalent on mobile. Genie was created to fill that gap, set up as an Internet Service Provider, a web portal and a suite of mobile information services, initially delivered via SMS to build habitual use before WAP was ready. On handsets, we were starting from scratch: tiny screens, 2G bandwidth, high latency, limited memory and a brand-new software stack.

Distribution was equally experimental. Before app stores existed, we shipped our software on physical CDs and partnered with BT Cellnet to bundle services directly through pre-pay phones. Handsets weren’t just devices; they became a channel to market — a way to deliver the mobile internet experience directly into users’ hands.

Long before software updates were a tap away, distribution was part of the design challenge. By bundling our services with physical devices and using CDs as delivery mechanisms, we weren’t just marketing a product , we were shaping the entire user journey from the moment someone unboxed their phone. It taught us that when the platform doesn’t yet exist, you have to build the ecosystem around it yourself. Designing not just the product, but the pathway it travels is a mindset that still applies today in emerging technologies, from spatial computing to AI-driven services.

WAP’s role

As part of BT’s delegation, I was a member of the WAP Forum, where we helped define the early standards that made mobile web experiences possible on constrained devices. WAP provided a shared way to render simple pages and trigger actions (like messaging and look-ups) on phones — a pragmatic bridge between the open web and the real-world limitations of mobile hardware.

Genie alpha: from web-to-SMS to information services

Our first public experiment was a simple Genie alpha site that allowed anyone to register for free and send an SMS from a web page to a mobile device. It was the first such service in the UK, and arguably the first commercial, public web-to-SMS service globally, launched in beta in 1998, before the official Genie Internet launch in March 1999.

As BBC coverage at the time noted, Genie already had thousands of text-message users before the official launch. Initially, it operated as a BT Cellnet web portal and value-added service. We then layered on basic information services — football scores, weather updates, news headlines — because they aligned with people’s daily habits.

Device partnerships shaped the portal

The client–server work we had begun with Nortel, Nokia, Motorola and Ericsson fed directly into our service ideas. We weren’t simply publishing WAP pages; we were designing interactions that devices could realistically deliver and aligning with manufacturers’ roadmaps wherever possible.

Speed to market mattered

Genie launched in beta in 1998, with the official launch in March 1999 — well ahead of Vodafone and Vivendi’s Vizzavi, which wasn’t announced until May 2000. Shipping something simple rather than waiting for perfect gave us a head-start and helped us build an early-adopter base. As the audience grew, major content brands (MTV, EMI, Dotmusic, Ministry of Sound) and gaming partners approached us to develop their first mobile services.

https://medium.com/media/1c7568ab2485ac932e3afd9b70c41358/href

The UK’s first WAP advert, created by BT Cellnet together with Genie, showing how we first introduced the idea of mobile internet to the public in the late 1990s.

What we Shipped (and why it mattered)

1. Network-agnostic content (before micropayments)

We deliberately made services accessible on any UK network, not just BT Cellnet. That widened our reach and created a powerful acquisition loop: customers who discovered Genie elsewhere often returned to BT Cellnet for better pricing, devices or support. The press at the time explicitly noted that Big Brother mobile services were available across all networks.

What we learned: Without mature billing rails inside the portal, attention and habit were the currency. Openness grew usage, and usage reduced churn for the host network.

2. Pricing that Unlocked Behavior: The Customer R&D Model

In November 2000, Genie launched the UK’s first unmetered mobile internet plan at £20 per month — a bold move designed to drive mass adoption and exploration.

This pricing decision was, in effect, a subsidy for customer research and development. At the time, mobile internet was universally billed on a terrifying per-minute or per-kilobyte basis, which paralyzed users with “fear of the bill” and prevented experimentation. The metered approach actively killed the very behavior we needed to discover.

What we learned: People cannot discover what a new medium is for under a metered plan. The flat-rate, “all-you-can-eat” model was a strategic call to remove that financial barrier, letting users experiment, fail, and develop sticky habitswithout punishment. For product builders today, the lesson is simple: your monetization model must encourage the desired user behavior, not restrict it.

3. G Live Music — Reimagining How Fans and Artists Connect

By the late 1990s, the music industry was waking up to the fact that the internet would radically change how artists reached their audiences, and that mobile could become the most important channel of all. Major labels were already experimenting: Danny van Emden returned to Virgin Records to establish the UK’s first New Media department, ensuring that every artist had an online presence and launching The Raft, one of the earliest label websites. EMI, Virgin’s parent company, quickly followed suit, with Fergal Gara and Eric Winbolt leading a dedicated new media team.

What they understood, and what many others missed, was that the next generation of fans might never experience the web primarily through a computer. Mobile, not desktop, was going to be the dominant way they discovered, consumed, and interacted with music. That made Genie a natural partner.

https://medium.com/media/a6c0323b4c475f694d22d7da6c8f06a8/href

At the top of the BT Tower, G Live Music launched with artists like Atomic Kitten on hand — marking a breakthrough moment when record labels, artists and Genie teamed up to connect directly with fans through their phones, long before the era of Twitter and streaming.

BT Retail had already been exploring voice-based services, while Genie was leading the market for SMS. The breakthrough idea was to combine the two into a hybrid experience, G Live Music, where EMI could send text alerts to fans that included not only headlines and updates, but also a phone number they could call to hear more.

To make the service engaging, I designed four distinct channels — Stars, Guitars, Heartbeats and Breakbeats — covering rock, indie, pop and dance music. Virgin hired BBC Radio 1’s Jo Wiley as the voice of the service, and record labels including Virgin, EMI, Chrysalis and Parlophone arranged for the artists themselves to record exclusive personal messages. This was more than a content feed . It was a direct line from band to fan, offering the kind of personalised access that would only become mainstream a decade later with platforms like Twitter.

G Live Music launched with major publicity at the top of the BT Tower, signalling a new direction for how artists and audiences could connect. It was an early example of how mobile services could go beyond delivering information — they could build relationships, turning devices into channels for authentic, human connection.

What we learned: Personalisation and proximity are powerful drivers of engagement. When artists’ voices reached fans directly — literally in their pockets — the emotional connection was far stronger than any banner ad or website visit. The project showed that successful mobile experiences are not just about content delivery, but about creating intimacy and community at scale.

4. Interactive Formats at Scale — From Big Brother to a Global Games Platform

One of the most powerful proofs of Genie’s approach came through our work on interactive entertainment, not just as content, but as a new category of mobile experience.

The Big Brother: Lifestylers project is often remembered as one of the first large-scale interactive mobile games in Europe, giving users the chance to shape virtual characters and influence outcomes on their phones. But the real story wasn’t the gameplay itself. It was the platform behind it.

When BT decided not to build a dedicated gaming platform in-house, the consultant I had been working with, Kevin Bradshaw, founded a startup to take the idea forward. That company — Digital Bridges — would go on to become one of the world’s top three mobile multiplayer gaming platforms, powering many of the early titles that defined the mobile games industry in the early 2000s.

By integrating the Digital Bridges platform into Genie, we were able to scale quickly and support a new wave of interactive formats. Big Brother: Lifestylers alone generated around 2.5 million play-minutes from roughly 60,000 players in just five weeks — a clear sign that people were willing to invest time and attention in mobile experiences when they were designed for the medium. And crucially, the service was available on all UK networks, reflecting Genie’s belief that reach and behaviour-building were more valuable than short-term exclusivity.

The Big Brother: Lifestylers WAP game, launched by Genie in partnership with Picofun and Channel 4, showcased the potential of interactive entertainment on mobile and helped accelerate the rise of Digital Bridges, which became one of the world’s leading multiplayer gaming platforms.

This phase of Genie’s evolution wasn’t just about a single hit. It was about building the infrastructure and partnerships that made new kinds of engagement possible. The success of Digital Bridges proved that mobile could support complex, multi-player, interactive formats long before app stores existed, and that those experiences could play a central role in shaping customer habits and expectations.

5. Device-level ambition (and why we pulled back): Nortel “Orbitor”

We explored integrating Genie-style services into Nortel’s Orbitor — a touchscreen, voice-recognition smartphone concept (1998).

The idea was right, but the technology was too early. Public museum records document both the ambition and the limitations of the device.

Working on Orbitor reinforced a lesson that would guide us throughout Genie’s development: visionary ideas are only as powerful as the technology that enables them. The device itself was remarkable — it combined voice, messaging, touchscreen navigation and over-the-air services, all running on Java long before that was standard in mobile environments. Even though the hardware and networks weren’t yet ready to support such ambitions at scale, the experience we were aiming for became a north star — shaping how we approached service design, interfaces and the broader future of mobile interaction.

What we learned: Vision needs timing. A decade later, iPhone-class hardware and OSs finally caught up with the idea.

6. GenieMobile — Extending the Portal Beyond the Phone

Genie Internet was also one of the earliest examples of what we would now call a virtual mobile operator. It operated entirely digitally, with no physical retail presence, building its brand, acquiring customers and delivering services exclusively online. That approach, radical for its time, allowed us to move quickly, experiment with new propositions and scale without the overhead of traditional mobile infrastructure.

While Genie was conceived as a mobile-first service, we knew from the start that the experience couldn’t end at the handset. Most users were still accessing the web from desktop computers, and they needed a simple way to manage their accounts, discover services and prepare content before going mobile. That insight led to GenieMobile, a companion desktop application designed to extend the value of the portal far beyond the small screen.

GenieMobile allowed users to manage and personalise their mobile internet experience before they even picked up their phone. Among its most popular features were:

- SMS alerts, delivering breaking information directly to a user’s handset as it happened.

- Email on WAP, providing free access to services like BT Internet, Talk21, Freeserve and Genie email accounts from anywhere in the UK.

- A personalised WAP menu, letting users select favourites on the Genie website and have them appear automatically on their phone for easier navigation.

- GenieOne, a unified inbox that brought together emails, faxes and voice messages in one place, accessible from either a PC or a mobile device.

At a time when over-the-air delivery was expensive and limited, GenieMobile acted as a seamless bridge between desktop and handset. It was one of the earliest attempts to synchronise services and preferences across devices, paving the way for the companion app model that would later become standard in the smartphone era.

GenieMobile’s web-to-handset portal liberated users from the nightmare of GenieMobile’s web-to-handset portal freed users from the hassle of configuring finicky ISP settings on clunky Nokia or Ericsson phones, enabling seamless SMS forwarding and address book management from any browser — a proto-cloud lifeline for professionals juggling work PCs and early mobiles. By cutting setup friction, it doubled daily engagement for power users, cementing loyalty and outpacing rivals stuck in mobile-only complexity. This experience-first innovation, despite primitive network limits, laid groundwork for the cloud era before 3G arrived

What we learned: A great mobile experience doesn’t start on the phone — it starts wherever the user is. GenieMobile showed that extending the journey across devices could deepen engagement and reduce friction, years before companion apps became the norm.

Building for a 3G Future — and Inventing the Cloud Before It Had a Name

That shift in perception created the foundation for what came next — a move beyond 2G services toward a future shaped by 3G networks, cloud storage, and entirely new kinds of mobile experiences.

While much of Genie’s early innovation focused on creating compelling services within the limits of 2G — like short-form entertainment, mobile radio, and interactive formats — we were already thinking well beyond those constraints. Inside the team, our discussions and prototypes increasingly centred on what would be possible once 3G networks, Java-enabled devices, and always-on connectivity became the norm.

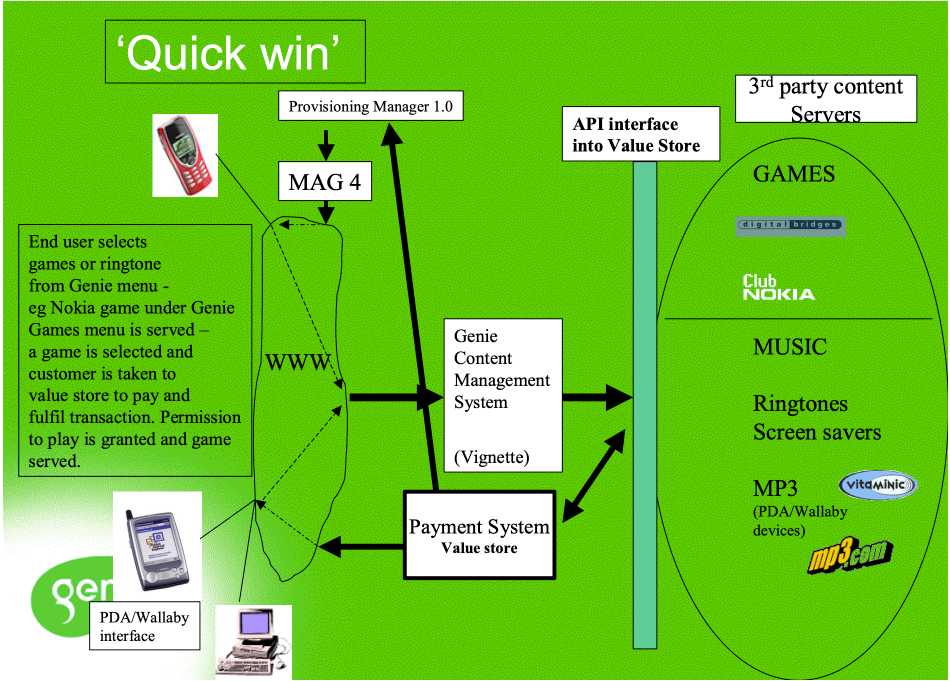

The ambition was bold: to create a fully integrated content ecosystem that could support music, games, messaging, ringtones, and even personal media — all underpinned by payment infrastructure, digital rights management (DRM), and a personal digital locker. We wanted people to be able to download content directly to their devices, store it in the cloud (though we didn’t yet use that word), and access it seamlessly across multiple touchpoints: phones, PDAs, and even desktop browsers.

Central to this vision was the idea of openness and interoperability. The platform would expose APIs that allowed third-party developers and content providers — including early partners like Digital Bridges, mp3.com, Vitaminic and Club Nokia — to plug their services directly into Genie’s ecosystem. This was a radical idea for its time: instead of a closed, operator-controlled platform, Genie aimed to become a value store — a distribution hub where customers could browse, purchase, and manage all their digital experiences from a single interface.

The diagram below, taken from one of our internal architecture documents, shows how advanced this thinking already was. It envisioned a system capable of provisioning content, handling payments, and enforcing usage permissions, in other words, a blueprint for the modern app store and cloud service model.

Even with the concept fully mapped out, one major challenge stood in the way: rights management and legal complexity. Delivering music, games and other premium content required navigating a labyrinth of contracts, distribution deals and licensing agreements. For a startup-scale venture inside BT — even one as ambitious as Genie — that proved difficult to resolve.

It’s telling that Vodafone, despite its scale and its deep partnership with Vivendi, ran into similar roadblocks. The ecosystem was simply too fragmented, and the legal and commercial incentives too misaligned, for anyone to solve the problem within the constraints of early-2000s mobile infrastructure. In the end, it took Apple’s vertically integrated approach — hardware, software, content, payments and rights all controlled under one roof — and the launch of the iPhone in 2007 to finally make the seamless mobile content model viable.

But even if we couldn’t deliver it at scale, the vision itself was prophetic. Genie’s platform work was one of the earliest serious attempts to combine content distribution, DRM, payment, storage, and developer integration into a single, customer-centric service. Seen with hindsight, it was a glimpse of the future, one that would eventually define the smartphone era.

Taking WAP to the Mainstream — and Telling a New Story

For all the innovation we were doing inside Genie, none of it would matter if people didn’t actually use it. The late 1990s mobile landscape was still defined by calls and texts, and the idea of browsing the internet on a phone was, for most people, more science fiction than reality. To succeed, we had to make the concept not only technically possible but emotionally compelling — and that meant changing the story around what a mobile phone was for.

One of the most significant milestones was the launch of the UK’s first pre-pay WAP phones, developed by Genie in partnership with BT Cellnet. This was the moment when mobile internet shifted from being an expensive, niche add-on to something anyone could access for under £100. The service connected people directly to news, music, sport, and entertainment — and, crucially, to a growing ecosystem of content partners such as EMI, BSkyB, Freeserve and The Guardian.

The launch was headline news. Sky News covered it as a turning point for mobile technology, highlighting how consumers could now go online without a computer for the first time. As Peter Erskine, Managing Director of BT Cellnet, explained in the report: “Suddenly, instead of buying a thousand-pound computer, people can access the internet just by buying a £99 phone. So suddenly people want the content that they can get.”

I followed by describing how quickly user behaviour would change once richer content became available: “People have a mobile phone and a Sony Walkman. By next year, people will just have their mobile phone and will be listening to their music on their mobile phone. They won’t need two cumbersome devices.”

This shift wasn’t just about hardware, it was about behaviour. Once people experienced the convenience of checking headlines, sending messages, or browsing music on a device they carried everywhere, the mental model of what a phone could do changed forever. And once that shift happened, the demand for more sophisticated services—richer media, better usability, deeper integration — accelerated dramatically.

https://medium.com/media/a0eedc8be53180bb40916e6239012f7b/href

Sky News report on the launch of the UK’s first pre-pay WAP phones, with commentary from Simon Robinson and BT Cellnet MD Peter Erskine on how mobile content and services were about to change consumer behaviour.

Looking back, this was more than a launch event; it marked a decisive turning point in customer perception. It showed that adoption depends as much on storytelling and value proposition as on technology, a lesson that would shape our thinking throughout Genie’s evolution.

How the market likely valued Genie (1999–2001)

In the dot-com era, portals and mobile data platforms were valued primarily for their strategic option value rather than present-day profits. Genie sat inside BT Cellnet as the face of future data revenue, with millions of registered users and nine-figure monthly WAP page views by mid-2001, and it was already expanding internationally across parts of Europe and Asia.

Comparables to anchor the range

- Vizzavi (Vodafone + Vivendi, 2000–2001): Launched with an investment plan of ~€1.6 bn, later described as worth £2.5 bn+ at its peak narrative (and higher in some analyst commentary). This shows that credible, pan-European mobile portals attracted billion-scale valuations on strategy alone.

- mmO2 flotation (Nov 2001): On demerger from BT, mmO2, which absorbed Genie’s assets into O2 Online/O2 Active, opened with a market cap between £6.5 bn and £7.3 bn, depending on the reference price. Genie was not listed separately, but its users, services and brand equity were part of that story.

A cautious, internal-style valuation

- Conservative (“cost-plus + scarcity”): £0.5 bn–£1.0 bn — reflecting accumulated build and marketing cost for a functioning, growing portal, plus a scarcity premium in a pre-3G market with few credible assets.

- Strategic (“option value vs. Vizzavi”): £1.0 bn–£2.0 bn — benchmarked against Vizzavi’s billion-euro scale and the idea that Genie could become a primary gateway for messaging, entertainment and games across BT’s European footprint.

There is no public filing that states “Genie was worth £X.” These figures synthesise comparable valuations, mmO2’s flotation, and Genie’s strategic role within BT Cellnet/BT — a realistic view of how a strategic finance team in 2000–2001 might have valued Genie internally.

Results that moved the needles

- Engagement & growth: By June 2001 Genie reported ~5.5 million registered users and ~103 million monthly WAP page impressions (BT listing documents).

- Lower churn / higher spend: In December 1999, BT Cellnet MD Peter Erskine told The Independent that Genie users spent more, were less likely to disconnect, and were expected to grow significantly.

- Industry recognition: Campaign’s 2001 Marketing Awards (Connections) named Genie Best Use of Mobile Phones/WAP.

None of this meant we had it all figured out — we didn’t. But the metrics suggested we were pulling the right levers for that era’s constraints.

Meanwhile at Vizzavi: brand scale without customer clarity

Vizzavi launched as a high-stakes Vodafone–Vivendi joint venture to unify web and mobile portals across Europe, combining Vivendi’s content (music, film, games) with Vodafone’s distribution. The bet: centralise the platform, push a premium brand, and own the customer front door. And their marketing budget was many times higher than Genie’s.

https://medium.com/media/33c94f6e1c1c808e7f284c972af8b9e3/href

The sales film that was played in Vodafone stores across the UK. Directed and produced by David Goodwin, it featured The Beatles’ Day in the Life with altered lyrics

Here’s how it played out:

- Operational fragility: A widely reported email outage during a core upgrade in December 2000 eroded user trust.

- Economic misalignment: Vivendi’s model relied on selling content; Vodafone bundled access, leaning toward “free to users” to drive network adoption — undercutting content margins.

- Strategic endgame: By August 2002 Vodafone bought out Vivendi’s stake, dropped the Vizzavi brand, and folded services into Vodafone live! (launched October 2002).

Takeaway: Scale is not a strategy. Without a clear customer job, a mega-portal becomes a cost centre looking for a purpose.

Side-by-side: the two playbooks

It’s easier to see the underlying patterns when you compare them directly. The table below shows how Genie and Vizzavi diverged across six critical dimensions — and how those choices determined their success or failure.

Figure 1 — A side-by-side comparison of Genie and Vizzavi across six strategic dimensions.

A brief postscript: the giffgaff echo

Years later, giffgaff would demonstrate a similar mindset: community-centred, online-only, and operating with a lean, agile model (launched in 2009 as an MVNO on O2). It was a different era, but the same bias toward simplicity and direct customer connection.

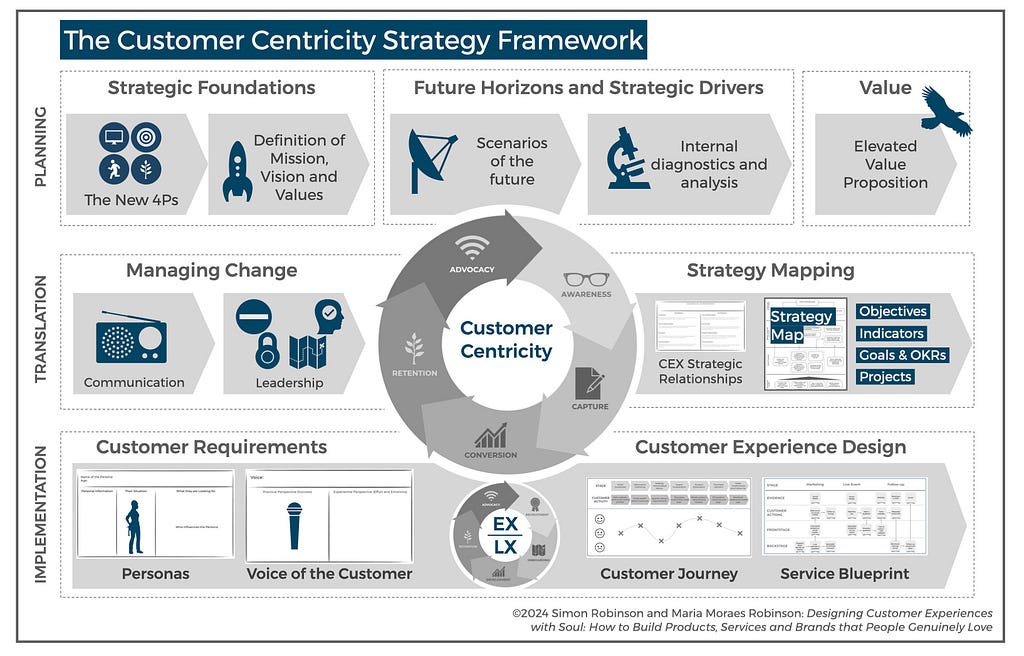

Seeing Genie Through the Lens of Customer Centricity

To understand why Genie succeeded where others stumbled, it helps to view the story through the structure of the Customer Centricity Strategy Framework — a way of thinking developed by Maria Moraes Robinson and I that grew directly out of this work.

At the time, we didn’t set out to “create a framework.” We were simply trying to build something that mattered to people. But over time, the logic behind those decisions became clear: we were designing intentionally around the customer lifecycle — not treating it as a marketing funnel, but as the central driver of strategy.

Every choice we made — from the earliest prototypes to our pricing model — was aimed at influencing that lifecycle: attracting users, building habits, deepening engagement, reducing churn and extending lifetime value.

1. Scanning future horizons

Genie’s origins lay in horizon-scanning. Even before the portal existed, we were exploring prototypes and scenarios for early smartphones, anticipating how connectivity, devices and user expectations would evolve. The goal was not to predict the future but to prepare for it.

2. Crafting a clear value proposition

Our value proposition was unambiguous: mobile phones were changing. They were no longer just for calls or texts — now, you could surf the BT Cellnet. This wasn’t about listing features; it was about reframing what a mobile phone wasand what it could do.

3. Leading organisational change

Transformation is never purely technical — it’s organisational and cultural too. We faced significant tensionstransitioning from a small team inside BT Cellnet to an independent startup. Our solution was deliberate: wemoved to our own office in Richmond-upon-Thames, a strategic firewall against head-office politics andcorporate bureaucracy. While the Vodafone-Vivendi joint venture slowed under the weight of reconciling brands,budgets, and bureaucracy, Genie operated with the velocity of a startup, maintaining a rapid, agile decision cycle — the essential prerequisite for breakthrough innovation. In today’s tech race, this same agility drives customer-centric wins. For example, it means aligning teams to prioritise user-friendly AI outputs over model complexity — think Grok’s conversational clarity over raw compute.

4. Designing strategy across people, processes and partners

We didn’t just set product targets — we mapped our strategy holistically across people, processes, marketing and partnerships. We built agile development cycles to release updates rapidly. We forged pioneering partnerships, such as the XY Network, that brought cultural relevance and fresh content. And we designed marketing around behaviours we wanted to encourage — not just around campaigns.

5. Putting experience before technology

Perhaps the most important principle was sequencing. We started with the experience we wanted to create and worked backwards to the technology required to deliver it. Vizzavi did the reverse — building a platform first and then searching for a purpose. That difference shaped everything: culture, speed, adoption and, ultimately, outcomes.

Practical Takeaways for Today’s Builders

The story of Genie offers enduring lessons that apply far beyond the mobile industry. These principles, drawn from what we learned two decades ago, are just as relevant whether you’re designing an AI-driven service, launching a SaaS product, or leading change inside a large organisation.

- Mindset Trumps Money: Capital is not Strategy. Don’t be intimidated by the war chests of large incumbents. Genie achieved superior results with roughly 1/20th of the funding Vizzavi commanded, proving that agility, a superior experience model, and focus on customer habit are far more valuable than a massive, misdirected investment.

- Make it Open by Default. Openness maximizes your surface area for learning, feedback, and growth — long before a final monetization model is ready. Don’t build walls unless they are essential for your core value proposition.

- Price to Encourage Exploration. Just as we used flat-rate plans to encourage mobile browsing, your pricing model should act as customer R&D, revealing real jobs-to-be-done rather than punishing early experimentation or metered usage.

- Program the Medium, Not Your Aspirations. Design services that work with the fundamental constraints of the underlying technology, not against them. In the age of Generative AI, this means recognizing an LLM’s propensity to hallucinate and designing the customer experience to manage verification, rather than forcing the model to act as a perfect, verifiable knowledge base.

- Ship Habits, Not Platforms. Focus on delivering ten real, sticky user behaviors quickly. This iterative approach creates more cumulative value than waiting years to launch one grand, perfect platform vision.

- Treat Timing as a Feature. If the enabling technology or market is not ready for the full vision, don’t kill the idea — change the plan. Adapt your scope and scale until technology adoption or infrastructure can catch up to the original vision.

- Align Incentives in Partnerships. Misaligned business models or conflicting partner incentives will tear even the best product apart. Ensure every partner — and every internal team — is motivated by the same measure of customer success.

- Let Results Speak for You. In a saturated market, adoption metrics, behavioral data, and organic growth speak louder than marketing adjectives. Focus on building something so valuable that the usage itself proves the strategy.

- Design for Real Behavior, Not Assumed Demand. Usage data and observed real-world customer actions must be the ultimate guide for your roadmap. Internal assumptions about what customers should want are the fastest path to irrelevance.

Looking Forward — Lessons That Still Matter

The story of Genie isn’t just a piece of telecoms history — it’s a blueprint for how transformative innovation happens. Every major technological shift — from mobile to cloud to AI — begins with a change in how we think about customers, value and organisational agility. We were experimenting with behaviours that hadn’t yet formed, building services for devices that didn’t quite exist, and designing for a future that was only just becoming possible.

That mindset — exploratory, adaptive and deeply customer-centred — remains the key to navigating today’s most complex innovation challenges. As the next wave of transformation unfolds, from AI-driven services to spatial interfaces, the opportunity is the same: to build not just technology, but meaningful experiences that people truly care about.

The future is never invented in theory. It’s built step by step — through experimentation, iteration and a relentless focus on real human needs. And it’s shaped not by technology itself, but by the experiences we design around it.

So the challenge for today’s builders is this: don’t just launch products — shape possibilities. Start with the experience, keep the customer at the centre of every decision, and you might just build the breakthrough the future has been waiting for.

References

Core Genie milestones & context

- The Guardian (Jul 2000) Upwardly mobile commerce: The arrival of wireless internet access is breeding a second wave of web portals (Genie launch, subscriber numbers)

- BBC News (Feb 1999). Cellnet dials up Internet first. (Genie launch; “wireless Internet” and “killer applications”).

- WAP Forum / Yahoo! Europe (Sep 2000). Yahoo! Europe and Genie announce portal agreement. (Notes Genie as UK’s mobile Internet leader; “first free-access Mobile ISP” and first working commercial pre-pay WAP service).

- TechMonitor (Nov 2000). BT Genie: your wish for unmetered mobile Internet is my command. (First unmetered £20/month mobile internet).

- Campaign (May 1997). Cellnet users gain access to Internet with Genie launch.

- BT Group (Listing Particulars, Sep 2001). Genie metrics (~5.5m registrations; ~103m monthly WAP page impressions).

Programming & services

- PRWeek (May 2000). MEDIA: XY brings music to mobile users. (XY Network; Somethin’ Else; audio with GPRS timing).

- The Guardian (May 2001). Channel 4 plans Big Brother radio show. (“Mobile customers on all UK networks will be able to access the free services…”)

- Campaign (May 2001). Cellnet’s shops design fly slots for Big Brother. (Genie as WAP provider).

- Picofun / Cision (Jul 2001). Picofun bakom största spelsuccén hittills i Europa. (Big Brother–Lifestylers: ~2.5m play-minutes in 5 weeks; ~60k active players).

Recognition

Impact on churn & spend

- The Independent (Dec 11, 1999). BT Cellnet aims to double users to 12m by 2003. (Erskine: Genie users spend more and are less likely to disconnect).

Device exploration

- Mobile Phone Museum. Nortel — One (Orbitor) (1998).

- York University Computer Museum. Nortel Europa / “Orbitor” background.

Vizzavi / Vodafone context

- DLGB (personal account). My Vizzavi Story.

- The Register (Dec 2000). Vizzavi bungles upgrade: leaves thousands without email.

- The Guardian (Aug 19 & Aug 30, 2002). Vodafone comes clean over Vizzavi transfer / Vodafone pulls plug on Vizzavi brand / Vodafone buys Vizzavi stake for £90m.

- Telecompaper (Oct 24, 2002). Vodafone launches Vodafone live!

Related / later echoes

- Wikipedia: giffgaff (UK MVNO; launched 2009).

Personal background & additional context

- Simon Robinson (2018). The Danger Trap of Dual-Transformation for Internal Startups.

- Simon Robinson (2013). A Brief (and Personal) History of Mobile Telephony 1992–2002.

Author

Simon Robinson is CEO (Worldwide) of Holonomics and a global thought leader on customer experience, systems thinking and strategic transformation. He is the co-author of several books, including Designing Customer Experiences with Soul and Deep Tech and the Amplified Organisation.

Start with the experience was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More