A PM playbook for failing fast: What (and what not) to do

“Fail fast” has become a defining principle of modern product development. It encouraged teams to move rapidly, validate assumptions, and avoid spending time on ideas that don’t work.

However, as experimentation has increased, so have the consequences. In organizations where products are linked to sensitive data, social influence, or financial decision-making, reckless speed can result in user loss, broken trust, or reputational damage.

This article presents a practical approach to ethical experimentation that maintains the speed and learning benefits of lean thinking while providing the structure and accountability required in today’s product market.

The ethical dilemma of failing fast

Failing fast isn’t always unethical; it becomes dangerous when speed takes priority over safety and user impact. Many teams unknowingly cross ethical lines by conducting experiments without consent, testing ideas that may negatively impact vulnerable groups, or ignoring early warning signs because they are solely concerned with performance metrics such as engagement or conversion.

The challenge is straightforward: companies want to learn quickly, but users expect products they can rely on. To balance those two needs, failure must be redefined as something to be managed responsibly rather than avoided.

Ethical experimentation doesn’t slow down teams. Instead, it provides guardrails to prevent you from falling off the edge while racing forward.

The product experimentation risk rubric

Not all experiments are equal. Changing a text font isn’t the same as changing a pricing model or altering how sensitive data is used.

That’s why teams need a simple way to classify risk before launching anything. A three-tier framework makes experimentation decisions clearer:

- Low-risk experiments — May include minor UI changes, non-critical copy updates, or visual improvements. These affect usability but pose little to no risk to users or the business

- Medium-risk experiments — Affect measurable parts of the user journey, such as onboarding flows, recommendation logic, or form layouts. Here, there’s a need for staged rollouts and closer monitoring because they may impact business performance or user experience

- High-risk experiments — Involve data privacy, pricing, financial outputs, security, or health-related insights. These must be handled with extreme caution because they have the potential to cause real harm if mismanaged

This rubric helps teams decide when to move fast and when to slow down. Low-risk ideas can be shipped rapidly, but high-risk experiments require additional planning, review, and stakeholder approval before launch.

The accountability checklist (lightweight RACI)

Speed without ownership creates chaos. Before starting any experiment, you should follow a simple pre-launch checklist:

- Define a clear hypothesis

- Assess the experiment’s risk level

- Set both success metrics and guardrail metrics

- Establish rollback triggers

- Develop stakeholder communication plans

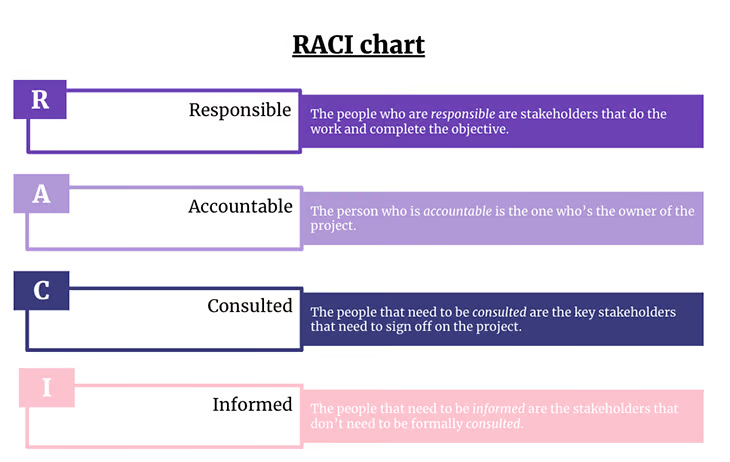

To guarantee clarity, associate each experiment with lightweight RACI alignment:

- Responsible — Who’s carrying out the experiment?

- Accountable — Who makes the final decision?

- Consulted — Who should provide feedback (like design, legal, security)?

- Informed — Who must be kept updated (like leadership, support, marketing)?

This structure helps prevent critical confusion during high-risk cycles.

Rollback plan framework

A rollback plan provides a safety net. Even great experiments can go wrong, and teams should not wait until a crisis occurs to decide how to respond. A simple rollback strategy contains the following:

- Trigger — Define the metrics or signals that indicate risk

- Decision — Determine who makes the call to stop or reverse

- Execution — Use feature flags or quick deployment to safely roll back

- Communication — Notify internal teams quickly and users when necessary

- Evaluation — Record lessons before repeating the experiment

Internal rollback notes help teams to respond faster. For example:

- “If churn rises by more than five percent or NPS drops below -20 during testing, revert to version A and notify the experiment channel immediately.”

External communication could be as simple as:

- “We temporarily rolled back a new feature while we improved performance. Thanks for your patience.”

This protects user trust even during experimentation.

Guardrail metrics that keep experiments ethical

Success metrics alone can be misleading. An experiment may boost engagement but also cause dissatisfaction, risk, or inequity. That is why teams must monitor guardrail data throughout each test.

These include:

- Reliability signals — Like app crashes, page latency, and error rates

- Trust indicators — Like rising complaint volume, increased subscription cancellations, or higher opt-out rates

- Equity impact — Such as uneven performance across regions, devices, or user groups

- Public sentiment trends — Visible through social mentions or support tickets

Guardrails make it harder for you to accidentally implicate users’ trust when trying to optimize their products.

Safer alternatives to failing fast

When the risk is high, “launch and pray” is a reckless strategy. Instead, you can adopt safer ways to learn quickly and strike a balance between innovation and accountability:

- Staged rollouts – Gradually expose one percent, then five percent, then 20 percent of users to test outcomes safely

- Opt-in pilots – Enable users or teams to voluntarily test new features

- Red-team reviews – Invite internal colleagues to question assumptions before launch

- Shadow experiments – Run alternative logic privately to test its impact before revealing it to users

Case studies

Now, to help you better understand what to do in practice, let’s take a look at some real-world examples of failing fast.

Slack: Iterating responsibly

Slack didn’t become a successful product by shipping wildly and crossing its fingers. Early on, the team shipped internally first, limiting exposure to real users until they had validated data and fixed any vulnerabilities.

In Slack’s blog, Stewart Butterfield wrote openly about its iterative development process, prioritizing real feedback loops over speed. Its approach shows that it’s possible to learn fast without causing unnecessary risk by layering iteration, transparency, and a deliberate rollout plan.

Facebook News Feed: Experimenting without guardrails

In contrast, Facebook’s 2006 launch of the News Feed became a case study in failing without ethical guardrails. Users were suddenly shown activity feeds that revealed behavior they had not intended to disclose publicly. There was no clear user consent and minimal explanation of what changed or why.

The Guardian and other major outlets reported an immediate and fierce backlash. Facebook saved the launch only after scrambling to implement new privacy settings and publicly apologized. The problem was not the experiment itself, but a lack of trust, openness, and user safety.

Final thoughts

The future of product development does not reject experimentation, but rather evolves it. “Failing fast” was effective when products were simpler and experimentation risks were fewer.

Today, failure requires structure. Teams must transition from speed-at-all-costs to responsible experimentation, which means learning quickly without sacrificing ethics, user trust, or product integrity. The new mindset is not to fail quickly, but to learn responsibly.

Featured image source: IconScout

The post A PM playbook for failing fast: What (and what not) to do appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

This post first appeared on Read More