Offline-first frontend apps in 2025: IndexedDB and SQLite in the browser and beyond

The web has always had an uneasy relationship with connectivity. Most applications are designed as if the network will be fast and reliable, and only later patched with loading states and error messages when that assumption fails. That mindset no longer matches how people actually use software.

Offline functionality is no longer a nice-to-have or an edge case. It is becoming a core principle of user experience design. Users expect apps to keep working when the network is slow, inconsistent, or completely unavailable. If your app loses data or locks up the moment a train enters a tunnel, users will notice.

Offline-first design flips the architecture: the local device becomes the primary source of truth, and the network becomes a background optimization rather than a hard dependency.

Why offline-first matters

Connectivity is unreliable in ways that are easy to ignore when you build from a well-connected laptop on a fast office network. In reality:

- Mobile users lose signal in elevators, subways, and parking garages

- Business travelers work from airplanes where WiFi is expensive, unstable, or nonexistent

- Underdeveloped regions still struggle with basic infrastructure

- Even in major cities, crowded events or network congestion can make a “connected” device effectively offline

Billions of people experience intermittent connectivity every day. Treating this as an edge case is no longer realistic.

Traditionally, the offline state was seen as a failure mode. You would show a spinner, error toast, or retry button and hope the network recovered. An offline-first architecture reverses that perspective. You design for the local device first and treat connectivity as an enhancement.

This closely matches user expectations. When someone opens an app, they expect:

- It to load instantly

- Their existing data to appear immediately

- Their work to be preserved regardless of connection quality

They do not want to think about network status, nor should they lose data because their train entered a tunnel.

An offline-first strategy embraces this: data is stored locally, interactions are instant, and the network is responsible for syncing changes in the background. The app behaves as if it were always online, even when it is not.

The current offline toolkit

Before looking at newer tools, it is useful to review the core browser APIs that make offline-first possible today. None of these are new, but they are still underused or misunderstood.

IndexedDB

IndexedDB is the browser’s built-in transactional database. It supports structured data, indexing, and transactions, and it runs entirely on the client.

Advantages:

- Built into every modern browser, no extra dependency required

- Capable of storing large datasets (often gigabytes, subject to browser limits)

- ACID-compliant transactions help prevent data corruption

- Indexes and range queries support efficient data access

- Asynchronous, non-blocking API that does not freeze the main thread

Disadvantages:

- The low-level API is verbose and historically callback-heavy (libraries such as

idbhelp a lot) - No JOINs or advanced relational query capabilities

- Subtle cross-browser differences and quirks

- Schema changes require careful versioning and migration logic

- More complex than

localStorage, but necessary for serious application data

For anything beyond simple key-value configuration, IndexedDB is the right tool.

Service workers

Service workers are the engine room of offline-first web apps. They run in a separate thread from your pages and can intercept network requests, enabling advanced caching and background synchronization.

A common pattern is cache-first fetching. The service worker:

- Serves responses from cache immediately for instant UI

- Fetches from the network in the background

- Updates the cache when newer data arrives

Combined with Background Sync, service workers can queue user actions while offline and replay them when connectivity returns, without requiring the user to keep the tab open. The result is an app where users never have to think about whether they are online or offline; their actions are preserved and synced automatically.

LocalStorage vs IndexedDB vs Cache API

Each browser storage mechanism has a different purpose:

LocalStorage

Simple but extremely limited. It:

- Usually caps at around 5–10 MB

- Uses a synchronous API that blocks the main thread

- Stores only strings

It is acceptable for small configuration values or flags, but not for user content or app data.

IndexedDB

Intended for structured application data, such as user-generated content, offline datasets, and complex objects. Treat it as your local application database.

Cache API

Stores HTTP responses, such as HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images, and API responses. It works closely with service workers to cache network resources and respond to fetch events.

A robust offline-first app will use all three:

- Cache API for static assets and API responses

- IndexedDB for application state and user data

- LocalStorage for trivial preferences or tokens where appropriate

New developments in 2025

Offline-first has evolved from a collection of custom workarounds into an ecosystem of purpose-built tools and patterns. The biggest shift is that full databases now run directly in the browser, often with built-in sync.

SQLite in the browser via WebAssembly

One of the most significant changes is running SQLite directly in the browser through WebAssembly. Projects such as sql.js and wa-sqlite have matured to the point where you can run a full SQL database, with millions of rows, entirely on the client.

This is a major shift:

- You can use standard SQL for queries and relational modeling

- Business logic and data transformations can run locally

- The database can live in memory or persist to IndexedDB or the Origin Private File System (OPFS)

In practice, this gives you a real relational database embedded in the browser, with no round trips for most operations.

WebAssembly-powered persistence and sync

Beyond “raw” SQLite, we are seeing full persistence layers compiled to WebAssembly. For example:

- Some stacks run SQLite in the browser and sync to an edge-hosted SQLite instance

- The browser behaves as a full node in a distributed database system

- Sync logic handles merging and replication between local and remote instances

In this model, the traditional client–server distinction starts to blur. The frontend is no longer a thin client that simply calls APIs. It is a full database node that happens to have a UI attached.

Hybrid local-first databases

Several libraries offer higher-level local-first abstractions built on top of IndexedDB, SQLite, or other storage engines. They differ in implementation, but share the same idea: keep data local and reactive, and sync it efficiently.

RxDB

Wraps IndexedDB and other storage adapters in a reactive API. Data changes emit observable streams that integrate naturally with reactive UI frameworks. It can sync with remote CouchDB-compatible backends.

PouchDB

Implements the CouchDB replication protocol in JavaScript. It supports bidirectional replication between the browser and a CouchDB (or Couch-compatible) server and has built-in conflict resolution tools.

ElectricSQL

Uses the PostgreSQL wire protocol to sync between a local client database and a remote Postgres. The client keeps a local replica and syncs changes incrementally, giving you a local-first app backed by a full relational database.

These tools give you higher-level sync semantics, conflict handling, and observability, instead of writing synchronization from scratch.

Architectural patterns

Building offline-first applications requires a different approach to data flow and state management. The following patterns appear repeatedly in successful offline-first architectures.

Cache-first pattern

In a cache-first pattern:

- The app immediately renders cached data

- A background request fetches fresh data

- The UI updates when newer data arrives

Users see content right away. The data might be slightly stale, but it is far better than a blank screen with a spinner.

This pattern is ideal for read-heavy experiences: news sites, documentation, and content-heavy dashboards. The key is to:

- Indicate data freshness clearly

- Give users a way to manually refresh if they need the latest data

Client-first pattern with optimistic UI

In a client-first pattern, user actions update local state immediately. For example:

- The user creates or edits a note

- The app writes the change to IndexedDB (or another local store)

- The UI updates instantly

- The change is enqueued for sync in the background

If the server later rejects the update, you roll back or reconcile the optimistic change.

This pattern delivers the fastest possible UX. Every interaction feels instant, and the network is effectively invisible.

The main challenge is conflict resolution. When multiple devices edit the same document while offline, you need a strategy to decide which changes win:

- Simple last-write-wins based on timestamps or version counters

- Operational transforms (like Google Docs)

- CRDTs (Conflict-free Replicated Data Types) that ensure mathematical convergence

- Manual resolution flows that surface conflicts to users

Your strategy should match your data model and the costs of incorrect merges.

Background sync with service workers

Service workers enable true background synchronization.

When the user performs an action offline:

- The app writes to local storage (for example, IndexedDB)

- The service worker registers a background sync task

- When connectivity returns, the browser triggers the sync event

- The service worker processes the queue even if the tab is closed

This makes offline actions durable. Users can close their laptop or browser and trust that the app will eventually sync their changes without manual intervention.

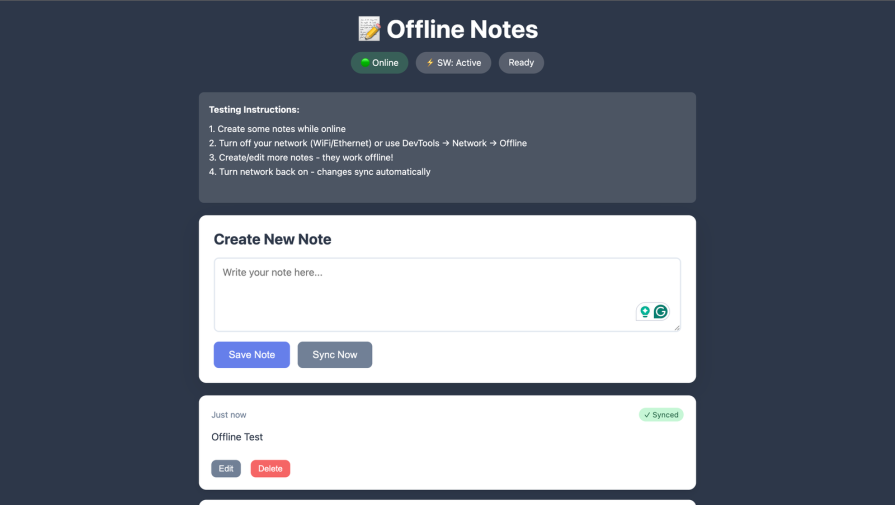

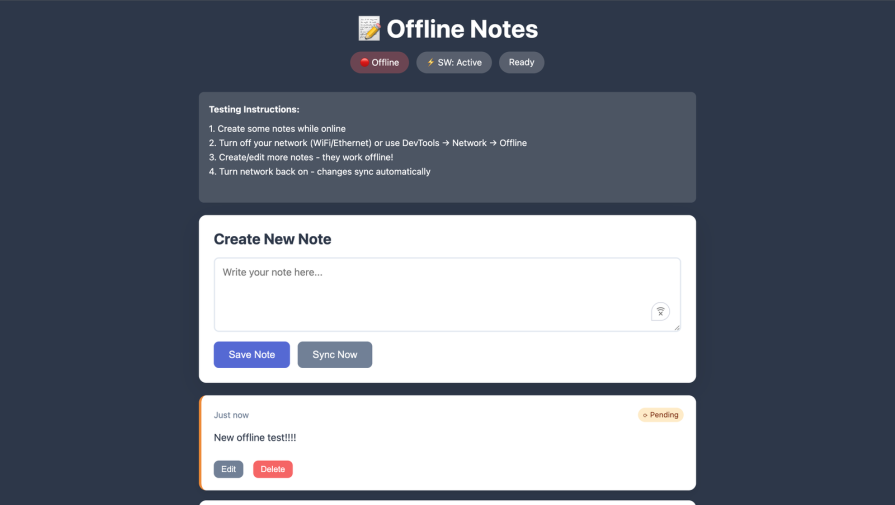

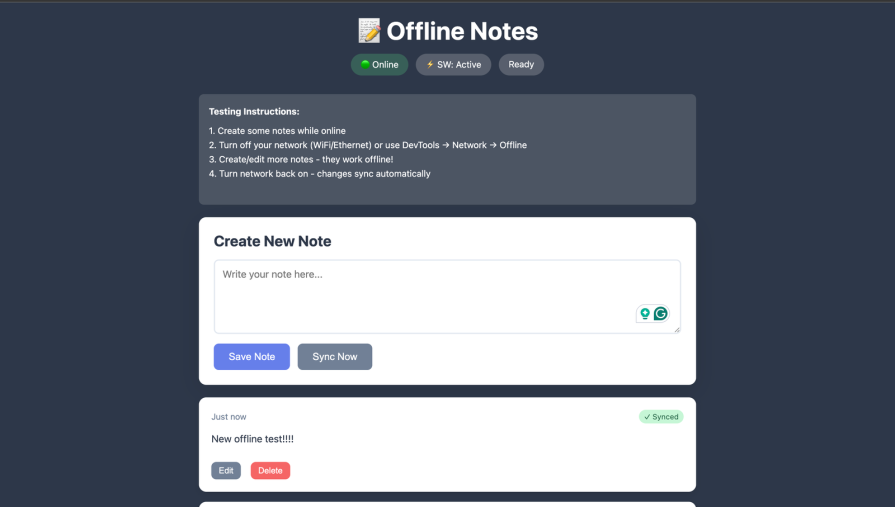

Practical demo: building an offline notes app

To see these ideas in context, consider a simple offline-first notes application that:

- Stores notes locally in IndexedDB

- Caches static assets via a service worker

- Works completely offline with instant interactions

- Syncs to a remote database when online

- Resolves conflicts with a last-write-wins strategy

Below are the key pieces of the architecture.

IndexedDB structure with sync queue

We start by setting up an IndexedDB database with two stores: one for notes and one for the sync queue.

class NotesDB {

constructor() {

this.db = null

this.dbName = "offline-notes-db"

this.version = 2

}

async init() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

const request = indexedDB.open(this.dbName, this.version)

request.onerror = () => reject(request.error)

request.onsuccess = () => {

this.db = request.result

resolve()

}

request.onupgradeneeded = (event) => {

const db = event.target.result

if (!db.objectStoreNames.contains("notes")) {

const notesStore = db.createObjectStore("notes", {

keyPath: "clientId",

})

notesStore.createIndex("updated", "updated", { unique: false })

notesStore.createIndex("serverId", "serverId", { unique: false })

}

if (!db.objectStoreNames.contains("syncQueue")) {

db.createObjectStore("syncQueue", {

keyPath: "id",

autoIncrement: true,

})

}

}

})

}

}

Optimistic UI update pattern

When creating a note, we write to IndexedDB and enqueue a sync operation before talking to the server. This allows creation while offline.

async addNote(content) {

const clientId = this.generateId()

const note = {

clientId,

serverId: null,

content,

created: Date.now(),

updated: Date.now(),

synced: false,

}

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

const tx = this.db.transaction(["notes", "syncQueue"], "readwrite")

const notesStore = tx.objectStore("notes")

notesStore.add(note)

const queueStore = tx.objectStore("syncQueue")

queueStore.add({

type: "create",

clientId,

content,

created: note.created,

updated: note.updated,

timestamp: Date.now(),

})

tx.oncomplete = () => resolve(note)

tx.onerror = () => reject(tx.error)

})

}

The UI can render the new note immediately after addNote resolves, independent of network status.

Service worker registration

The main script registers the service worker and listens for messages about sync completion.

async function registerServiceWorker() {

const statusEl = document.getElementById("swStatusText")

if (!("serviceWorker" in navigator)) {

console.log("Service workers not supported")

if (statusEl) statusEl.textContent = "SW: Not supported"

return

}

try {

const registration = await navigator.serviceWorker.register("/sw.js")

console.log("Service worker registered:", registration)

if (statusEl) statusEl.textContent = " SW: Active"

navigator.serviceWorker.addEventListener("message", (event) => {

if (event.data?.type === "SYNC_COMPLETE") {

console.log("Background sync completed")

renderNotes()

}

})

} catch (error) {

console.error("Service worker registration failed:", error)

if (statusEl) statusEl.textContent = "SW: Failed"

}

}

SW: Active"

navigator.serviceWorker.addEventListener("message", (event) => {

if (event.data?.type === "SYNC_COMPLETE") {

console.log("Background sync completed")

renderNotes()

}

})

} catch (error) {

console.error("Service worker registration failed:", error)

if (statusEl) statusEl.textContent = "SW: Failed"

}

}

Background sync

In the service worker, we listen for sync events and process queued operations.

self.addEventListener("sync", (event) => {

if (event.tag === "sync-notes") {

event.waitUntil(syncNotes())

}

})

async function syncNotes() {

const db = await initDB()

const queue = await db.getAll("sync-queue")

for (const item of queue) {

try {

await syncToServer(item)

await db.delete("sync-queue", item.id)

} catch (error) {

console.error("Sync failed:", error)

// Will retry on the next sync event

}

}

}

async function syncToServer(item) {

const response = await fetch("/api/notes", {

method: "POST",

headers: { "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body: JSON.stringify(item),

})

if (!response.ok) throw new Error("Sync failed")

}

Background sync with queue processing

A more advanced version of syncNotes might look like this:

self.addEventListener("sync", (event) => {

console.log("[SW] Background sync triggered:", event.tag)

if (event.tag === "sync-notes") {

event.waitUntil(syncNotes())

}

})

async function syncNotes() {

console.log("[SW] Starting background sync...")

try {

const db = await openDB()

const queue = await getSyncQueue(db)

if (queue.length === 0) {

console.log("[SW] Nothing to sync")

return

}

console.log(`[SW] Syncing ${queue.length} operations...`)

for (const operation of queue) {

try {

await syncOperation(operation)

await removeSyncOperation(db, operation.id)

console.log("[SW] Synced:", operation.type, operation.id)

} catch (error) {

console.error("[SW] Failed to sync:", operation.type, error)

// Keep in queue for retry

throw error

}

}

const clients = await self.clients.matchAll()

clients.forEach((client) => {

client.postMessage({ type: "SYNC_COMPLETE" })

})

console.log("[SW] Sync complete")

} catch (error) {

console.error("[SW] Sync failed:", error)

throw error

}

}

Conflict resolution pattern

The service worker can resolve and propagate sync operations based on operation type.

async function syncOperation(operation) {

let response

switch (operation.type) {

case "create": {

response = await fetch(`${API_URL}/notes`, {

method: "POST",

headers: { "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body: JSON.stringify({

content: operation.content,

clientId: operation.clientId,

created: operation.created,

updated: operation.updated,

}),

})

if (!response.ok) throw new Error(`HTTP ${response.status}`)

const serverNote = await response.json()

const db = await openDB()

await markNoteSynced(db, operation.clientId, serverNote.id)

break

}

case "update": {

if (!operation.serverId) {

console.log("[SW] Skipping update, no server ID yet")

return

}

response = await fetch(`${API_URL}/notes/${operation.serverId}`, {

method: "PUT",

headers: { "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body: JSON.stringify({

content: operation.content,

updated: operation.updated,

}),

})

if (!response.ok) throw new Error(`HTTP ${response.status}`)

break

}

case "delete": {

if (!operation.serverId) {

console.log("[SW] Skipping delete, no server ID yet")

return

}

response = await fetch(`${API_URL}/notes/${operation.serverId}`, {

method: "DELETE",

})

if (!response.ok && response.status !== 404) {

throw new Error(`HTTP ${response.status}`)

}

break

}

}

}

This demo app illustrates the core offline-first patterns:

- Local-first writes with optimistic UI

- A durable sync queue in IndexedDB

- Background sync via service workers

- Simple last-write-wins conflict handling:

Challenges and tradeoffs

Offline-first architectures are powerful, but they introduce real complexity.

Conflict resolution in multi-device apps

The hardest problem is conflicting edits. For example, a user might edit the same note on both their phone and laptop while both are offline. When each device syncs, which version should win?

Options include:

- Last-write-wins based on timestamps or version counters

- Operational transforms (OT), which merge edits at the operation level

- CRDTs, which mathematically guarantee convergence

- Manual conflict resolution flows where the user chooses the correct version

There is no universal answer. Your approach depends on:

- The domain (notes vs financial transactions)

- How important precise merging is

- How tolerant users are of manual conflict resolution

Data consistency vs latency

Offline-first architectures favor low latency over strict consistency. The app shows local state immediately, even if that state is stale compared to the server.

For many domains, this is a good tradeoff. Users prefer a responsive UI that occasionally shows slightly stale data to a slow UI that is always consistent.

However, some domains require stronger guarantees, such as:

- Financial operations

- Inventory and stock allocation

- Ticketing and booking systems

For these, you might combine patterns:

- Optimistic reads and non-critical writes

- Strongly consistent writes for critical operations that must be confirmed by the server before committing locally

Storage limits across browsers

Browsers enforce quotas to prevent sites from consuming unbounded disk space. Limits vary across engines and are not always clearly documented. Roughly:

- Chromium-based browsers use a dynamic quota based on available disk space

- Firefox limits total per origin and per group, often to a portion of free disk space

- Safari is stricter and more conservative, sometimes prompting users sooner

Your app needs to handle quota-exceeded errors gracefully. Useful strategies include:

- Pruning old or derived data

- Compressing large payloads where appropriate

- Giving users a UI to clear cached content or reduce offline storage

Best practices

Building robust offline-first apps requires upfront planning rather than bolt-on fixes.

Plan sync strategies early

Do not treat synchronization as an afterthought. Design your data model and sync approach from the beginning. Establish:

- What conflict resolution strategy you will use

- How you handle partial sync, where some operations succeed and others fail

- What your retention policy is for offline data

Prioritize user control and transparency

Silent syncing without any visibility can erode trust. Expose enough state that users feel in control:

- Visible sync status (syncing, up to date, conflicts)

- A manual “sync now” action for power users

- A way to see pending operations in the queue

- Settings to manage offline storage

Users are more tolerant of edge cases when they understand what is happening.

Test offline flows rigorously

Offline behavior is often the least tested part of an app. Make it part of your regular workflow:

- Use Chrome DevTools offline and throttling modes

- Test slow, flaky networks, not just “online vs offline”

- Simulate sync interruptions mid-request

- Test conflict scenarios across multiple devices

- Verify behavior across browsers and platforms

Automated end-to-end tests with tools like Playwright or Cypress can help you simulate network conditions programmatically.

Monitor sync health

Treat sync as a first-class subsystem and instrument it accordingly. Useful metrics include:

- Sync success and failure rates

- Time from reconnection to a fully synced state

- Conflict frequency

- Queue depth over time

Spikes in failures or queue depth are early signals of API issues or bugs that users may not report immediately.

Handle storage gracefully

Proactively check storage usage and warn users when they are approaching limits:

async function checkStorageQuota() {

if ("storage" in navigator && "estimate" in navigator.storage) {

const estimate = await navigator.storage.estimate()

const percentUsed = (estimate.usage / estimate.quota) * 100

if (percentUsed > 80) {

notifyUser("Storage almost full. Consider clearing old offline data.")

}

}

}

This prevents sudden failures and gives users a chance to free up space.

Conclusion

Offline-first used to be an afterthought. In 2025, it is a core pillar of resilient user experience design. The browser platform and ecosystem have matured to support this:

- IndexedDB and the Cache API provide powerful primitives

- Service workers and Background Sync enable durable offline actions

- SQLite in the browser and WebAssembly-powered sync engines bring full databases client-side

- Local-first libraries add higher-level replication and conflict handling

The result is a shift in philosophy. The network is unreliable. Devices are powerful. Users expect instant interactions. Offline-first design accepts these constraints and builds around them.

The future of web apps looks increasingly local-first: the local device acts as the primary source of truth, the UI is driven by local state in real time, and the network is an optimization rather than a requirement. Apps that adopt this model are not only better offline; they are faster and more resilient even when the network is perfect.

The real question is no longer whether you should support offline. It is how quickly you can adopt offline-first principles and architectures in the apps you are building today.

The post Offline-first frontend apps in 2025: IndexedDB and SQLite in the browser and beyond appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

This post first appeared on Read More

SW: Active"

navigator.serviceWorker.addEventListener("message", (event) => {

if (event.data?.type === "SYNC_COMPLETE") {

console.log("Background sync completed")

renderNotes()

}

})

} catch (error) {

console.error("Service worker registration failed:", error)

if (statusEl) statusEl.textContent = "SW: Failed"

}

}

SW: Active"

navigator.serviceWorker.addEventListener("message", (event) => {

if (event.data?.type === "SYNC_COMPLETE") {

console.log("Background sync completed")

renderNotes()

}

})

} catch (error) {

console.error("Service worker registration failed:", error)

if (statusEl) statusEl.textContent = "SW: Failed"

}

}