A case against MVPs: Why I’ve grown to hate “The Lean Startup”

“The Lean Startup” by Eric Ries tends to be one of the first books aspiring product managers encounter on their learning journey. It’s a solid piece that lays out the foundations of lean development practices and showcases what startup life looks like.

But there’s one problem…

Whether it intended it or not, the book contributed to a toxic MVP culture that many PMs now fall into. Don’t get me wrong, MVPs are great, but they’re far from a perfect solution.

As an alternative, this article outlines a case against MVPs, drawing on my own personal experience in the realm of product management.

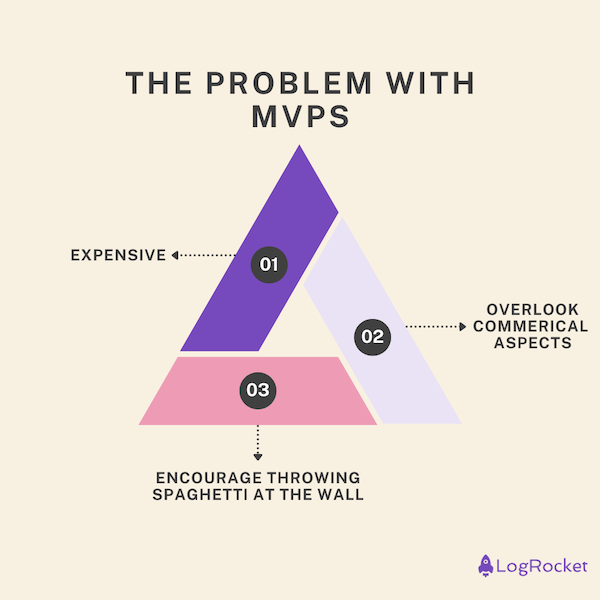

The problem with MVPs

Minimum viable products (MVPs) are great for validating product ideas and getting customer insights. However, they come with their own problems and limitations:

They’re very expensive

The biggest issue with the whole build-measure-learn cycle is that it’s more expensive than it’s depicted.

Yes, iterating on MVPs is significantly cheaper than spending a couple of months on building a whole product upfront. But even if you iterate weekly, it’s still a week’s worth of development down the drain — even if you’re just prototyping.

They overlook commercial aspects

Building a product customers love isn’t that hard; the challenge is building a product that grows quickly and earns revenue along the way.

Oftentimes, MVP-focused development is the slowest way to get there.

Before even thinking about your MVP you should ensure that you target the right customer segment, secure enough room for growth, and test the willingness of people to pay.

They encourage throwing spaghetti at the wall

The ability to “just test something” with an MVP encourages people to throw spaghetti at the wall. I’m sure you’ve come across people saying things like:

- Do you have an idea you’re not sure is gonna work? Test it with MVP.

- Are you unsure if people will pay for it? Test it with MVP.

- Will you get enough traffic on your website? Test it with MVP.

Although you might get lucky, the odds are slim.

Building products is a more sophisticated process than just testing every single idea you have until you find something that sticks.

MVPs can help you validate the strategy, but they’re better suited as an add-on to the strategic planning process than as a replacement for it.

What to do before investing in an MVP

Now that I’ve covered the limitations of MVPs, let’s discuss how to combat them.

In a nutshell, you need to do some homework before building and shipping your tests. Putting in more thought before testing helps you not only maximize chances of testing the right thing, but also makes drawing learnings and conclusions easier.

Before investing in an MVP, think of these two buckets:

Segment hypothesis

Start any product initiative by defining the segment of users you’re going to target.

Having clarity on who your customers are (or might be) allows you to:

- Build more focused MVPs with a higher chance of winning

- Test on users who are most likely to stick rather than testing with random people

- Draw better learnings and determine what value proposition (MVP) works with what specific segments, helping you to expand or narrow down the product scope

Here are some criteria for a great user segment:

- A painful problem that needs to be solved

- People in the segment represent similar categories of thinking (have similar expectations and beliefs)

- It’s big enough to fuel initial growth

- It’s small enough that you can actually dominate it

Depending on your starting point, figuring out your target segment will look different. However, most product initiatives already have a pain point in mind that they want to solve for. The workflow looks something like this:

- Define a clear problem — What exactly is the problem you want to solve? Get specific. Vaguely-defined problems lead to vaguely-defined segments

- Brainstorm initial segments — Unless you have expert knowledge, start brainstorming which segment of users suffers from your target problem the most

- Evaluate segments — Make sure all segments on your list are viable. Revisit the criteria of a great user segment and leave only those that tick all four boxes (painful problem, similar expectations, big enough, small enough)

- Validate segments — If you’re left with a couple of user segments, validate which ones make the most sense to target. User interviews help a lot with this

After following these four steps, you’ll end up with a strong segment hypothesis (if there’s more than one, it’s fine). You still need to validate it further with an MVP, but at least you have a good starting point.

Business model hypothesis

It doesn’t matter how amazing your product is if no one knows it exists, or if people aren’t willing to pay you for using it.

Start by asking yourself:

- Are people willing to pay for your solution to the problem?

- Is there a way to build a growth loop?

There are a few ways to discover if people will pay for your product:

- Direct question — Ask a user if they’d pay $10 for your product if it did X. If they say yes, ask them if they would pay $12. Keep increasing until you discover a ceiling

- Probability question — If you have a minimum price you need to charge to be profitable, ask users the probability they’d pay that much from one to five. For people who say between one and three, the price is too high

- Van Westendorp study — A more robust and quantitative way to test willingness to pay is to run a Van Westendorp study, which is a surveying and analysis method that helps you define the range of acceptable prices. Read more on this technique here

Is a growth loop possible?

Great products are based on growth loops, meaning each cohort of users leads to a new cohort of users. There are four main ways to acquire users:

- SEO — Users come from SERP and either create their own content (which is further indexed in SERP) or buy a product, giving resources for the company to generate more content

- Performance marketing — Users come to the product through paid ad, and purchase the product, giving the company cash for further marketing

- Sales — Salesforce outreaches to clients and closes deals, leading to a cash influx, allowing to hire more salesforce

- Virality — Users invite other users, mostly to get more value from the product itself (social and collaboration products), or earn a benefit (e.g. referral program)

To hypothesize if any of those loops make sense, evaluate your target audience, and if:

- They’re a small group of users with a very high willingness-to-pay, the sales loop should work

- They’re a big group of users who try to solve their problem by searching solutions on the internet, SEO should work

- They’re willing to invite other people to benefit from the product together, consider virality

- You can target very precisely selected users with ads, consider performance marketing

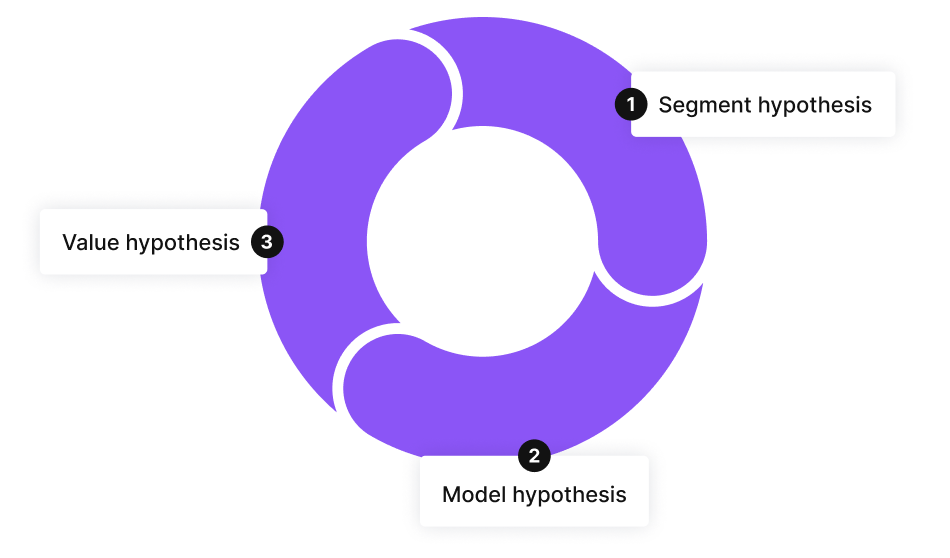

The new learning cycle

The build-measure-learn cycle is an overly simplistic and inefficient loop, mostly because it’s expensive and doesn’t include key commercial factors related to building a product.

However, MVPs still make sense per se; you just need to do some homework beforehand.

You can organize your early product development into a three-step loop:

- Start by narrowing down your segment hypothesis. You should target a very specific target group from day one to maximize learnings

- Figure out if building a product for a particular segment to solve a particular problem even makes sense. Check for willingness-to-pay and growth possibilities

- Test if you can actually deliver good enough value to attract the target segment and kickstart your growth

- Repeat if needed

Common problems

Odds are you’ll need to spin the loop a couple of times before you find a true product-market fit. Don’t get discouraged. The goal of this process is to maximize your learning speed, not to build a great product from day one (although it does increase the odds of doing so).

The most common challenges you’ll encounter are:

- Failed segment hypothesis:

- The segment is too small to build a business

- The segment is too big and unfocused to effectively target

- Users don’t suffer from the problem after all, or it’s not painful enough for them to want to solve it

- Failed business model hypothesis

- People aren’t converting and aren’t willing to pay for the product

- The acquisition channels you set up aren’t working as expected

- Failed value hypothesis

- People don’t perceive the MVP as valuable

- The product itself isn’t usable

Final thoughts

Take the learnings from these problems and adjust your hypotheses. Remember, they’re interconnected. For example, if people aren’t willing to pay the price you set, you can adjust your:

- Segment hypothesis — Target a different audience

- Business model hypothesis — Charge less and find less expensive acquisition methods

- Value hypothesis — Add extra value to increase willingness-to-pay

Those are learnings and possibilities that would be impossible if you just randomly built MVPs without having a specific segment and business model in mind. You don’t only want to learn what doesn’t work, but also why it doesn’t work.

Do your homework first, then jump to building an MVP.

Featured image source: IconScout

The post A case against MVPs: Why I’ve grown to hate “The Lean Startup” appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

This post first appeared on Read More