A complete guide to UX design techniques

UX design can get confusing. There’s so much to do in so little time that it can be hard to know what to tackle first and in what order.

That’s why it’s important to get your design techniques right.

Simply put, a design technique is a structured approach to achieving one’s goals. It’s like a tool you use to get the work done.

They range from broad, strategic research techniques to very specific validation exercises.

UX design is the art and science of choosing the right UX techniques and applying them correctly and in the right order. Simple as that.

To help you hone your skills, this article unpacks some of the most widely used design techniques.

Editor’s note: This blog was rewritten 11 June 2025 by Bart Krawczyk to explain UX techniques across the entire design lifecycle, as well as to add coverage of user research, ideation, prototyping, testing, and validation.

User research techniques

The first step of every UX initiative is to deeply understand your users and their needs. Let’s take a look at a few techniques that can help you with that.

User interviews

If there were one single technique every UX designer should master, it’s user interviews. The ability to get relevant insights from actual users is incredibly valuable.

There are two main types of user interviews:

- Exploratory — You ask open-ended questions about users’ lives and the way they handle particular challenges to get as much inspiration and learning as possible

- Validation — You come with a set of specific assumptions and beliefs about the user and ask questions to validate if your understanding is right

The quality of your user interviews often translates directly to the quality of your end designs.

Customer surveys

Surveys are the main way for you to get quantitative insights — that is, statistically significant information about your users.

They allow you to cheaply validate your beliefs and gather unique insights that would be hard to spot during interviews with a limited number of users.

A great survey consists of:

- Well-written, non-leading, and non-biased questions

- A properly segmented target group – meaning you ask the right people

- A good screener to further filter out the right people

- A great volume of responses, usually 100+

- A proper analysis of results

Field studies

Field studies, often known as ethnographic studies, consist of observing users in their natural environment.

For example, once I was working on improving the cashier experience in a retail store, so I just stood behind the counter for a whole day and observed how they worked and what they clicked in the POS software.

It helps us build stronger empathy with users and notice patterns and interactions that they wouldn’t even consider mentioning during other types of studies.

Diary studies

Diary studies are one of the more sophisticated methods of user research.

You start by defining what questions a user group should answer every day, and then ask them to do so. It can range from filling out a Google form, having a scheduled call, or writing in a literal diary.

This type of research helps you uncover users’ attitudes over time. For example, how fitness motivations change over time from January 1st to February 1st.

Analysis and ideation techniques

Research itself is a waste of time if it doesn’t lead to any tangible outcomes. Let’s take a look at techniques that help you turn research into actionable artifacts.

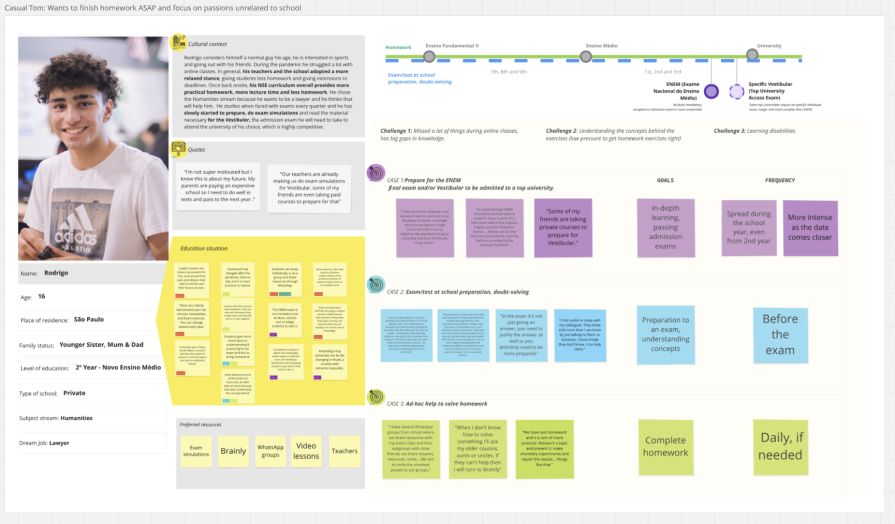

Personas

User personas are a great way to synthesize your findings from user research. It’s a single document that contains the most important information about a particular user segment, such as:

- Their goals

- Pain points they experience

- Relevant quotes

- Context of use

Later, you can test your ideas and solutions by checking the relevance with the user persona, greatly improving the chance that the final solution will be what users actually need.

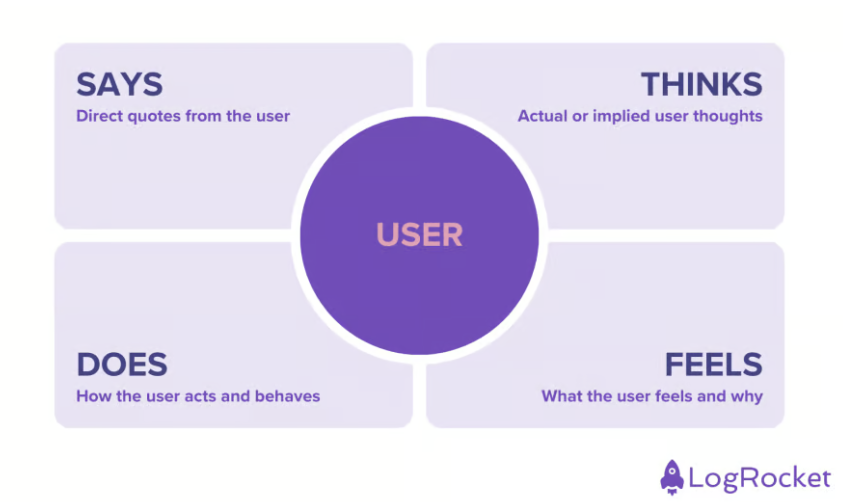

Empathy maps

An empathy map has a similar purpose to user persona — that is, to aggregate insights into a cohesive artifacts:

You make one by aggregating what the user says, thinks, does, and feels into a small canvas.

Personally, I use them as an extension for the user persona, but almost never as a standalone tool — persona just seems to do the job better, with less artificial divisions.

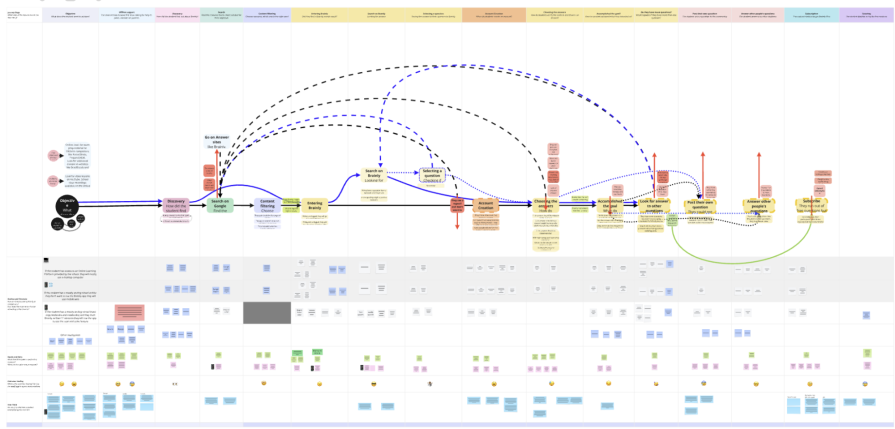

Journey maps

A user journey map is a visualization of the path a user takes when solving a particular problem. It can work both as a synthesis tool (summarizing the current user journey of a user) and as an ideation tool (ideating the ideal user journey your product should create):

By mapping what people experience at each step, you can “feel” the journey, making it easier to empathise with the user and design a product that makes sense from the beginning to the end.

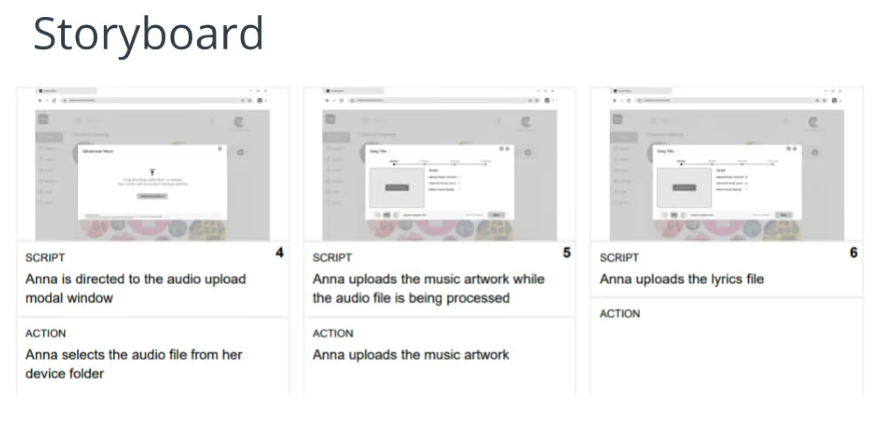

Storyboarding

Storyboarding is a more detailed way of describing and visualizing a specific part of a user journey.

You can use screenshots if you’re working on an existing user journey, or a simple mockup if you are ideating a new user journey:

By seeing how the journey looks visually, it’s easier to spot UX challenges and ideate alternate solutions than when just working on a high-level description of the journey.

Jobs to be done

Jobs to be done synthesize and summarize what specific objectives users are trying to achieve:

By understanding the end goal users are trying to achieve, you can design innovative solutions in a non-biased way.

Affinity diagramming

Affinity mapping is a way of organizing large amounts of insights into more manageable, related groups.

For example, if you mapped 100 sticky notes of insights and interesting observations from your research, instead of processing all of them separately, you should first group them into related categories.

Prioritizing, discussing, and acting on ~10 groups of observations is much more manageable than working on ~100 individual observations.

Information architecture and content techniques

Information architecture is an often-neglected topic, as people tend to often associate it exclusively with navigation design. But with products getting increasingly complex, a proper IA is needed from the very beginning, even on a feature level.

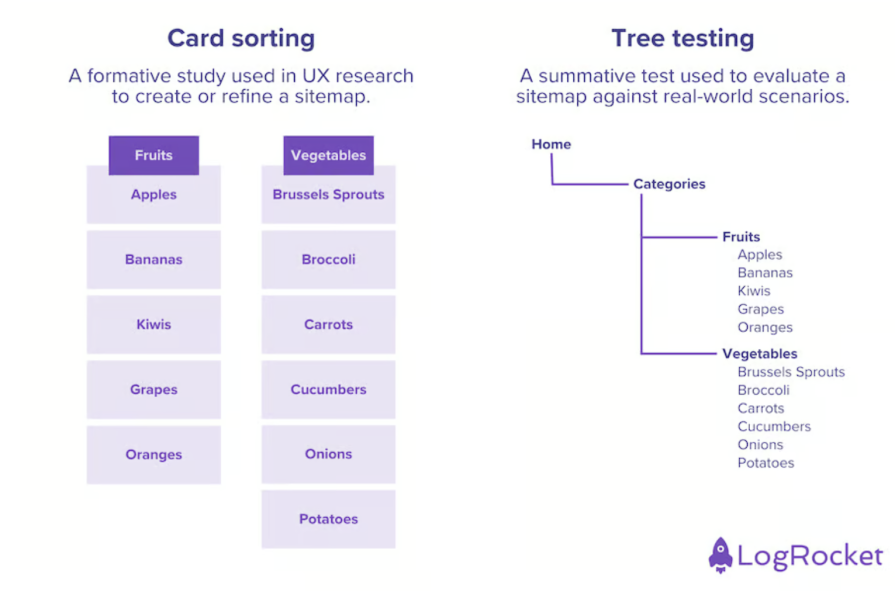

Card sorting

Card sorting is a great way to figure out how to structure information on your website and product.

Say you have 40 subpages and you’re unsure how to organize them. Ask a couple of users to group these under specific categories and that’s it:

Card sorting usually happens in two stages:

- Open card sorting — Users are given a list of items, but they are responsible for grouping and naming specific categories. A great way to explore what types of categories come to users’ minds naturally

- Closed card sorting — Same thing, but the categories are already predefined. Good to validate what type of items should be part of what category

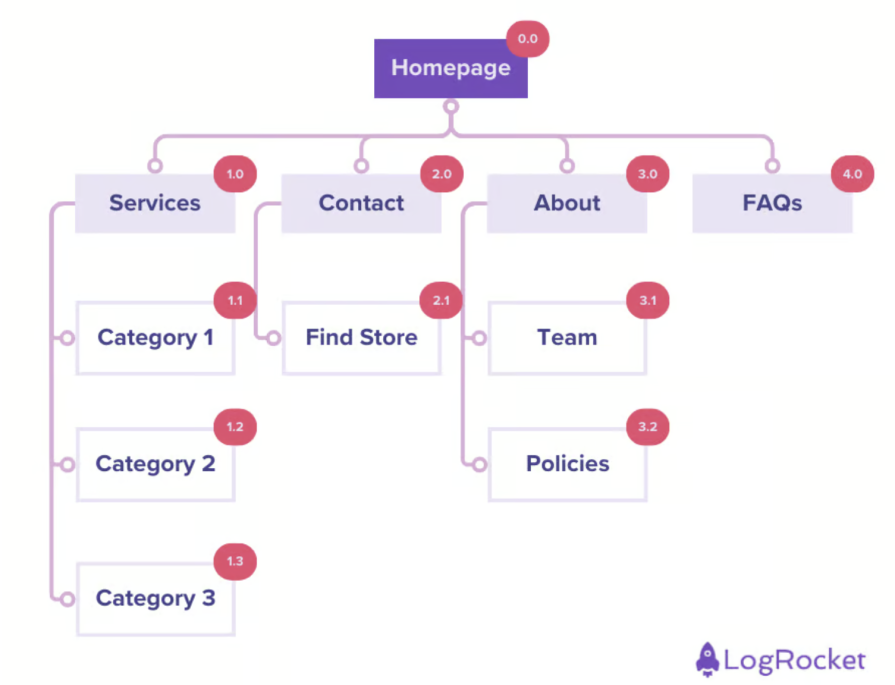

Sitemap creation

After the card sorting, you can map a newly established page structure in the form of a sitemap — a hierarchical order of categories and subcategories:

Sitemaps help you conduct a sanity check if:

- Everything makes logical sense

- There’s not too many or too few sub-categories for any particular category

- You didn’t miss anything

Then they serve as documentation, making any new hierarchy-related initiative, as well as onboarding new designers, significantly easier.

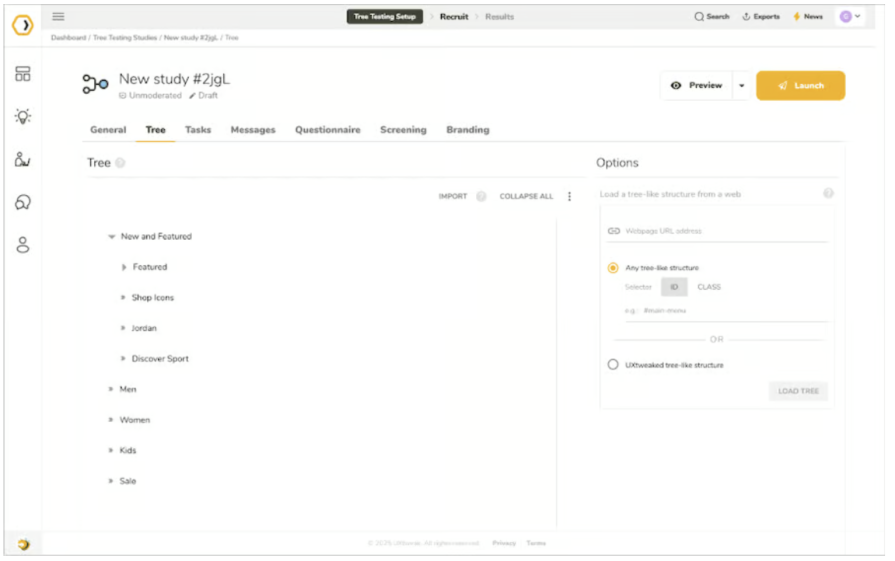

Tree testing

Card testing can help you discover (open) and refine (closed) categories and your information hierarchy. Then, the sitemap allows you to concisely map the outcomes.

Once, you’ve done that you can test it with tree testing:

Based on card sorting results, you create an actual navigation hierarchy and then test it with users. You usually give users a task, such as “find a page X”, and observe how they navigate towards it and if they click through the right categories, and if not, where the confusion is.

Many remote user testing tools, such as UXTweak, even have a dedicated mode for tree testing:

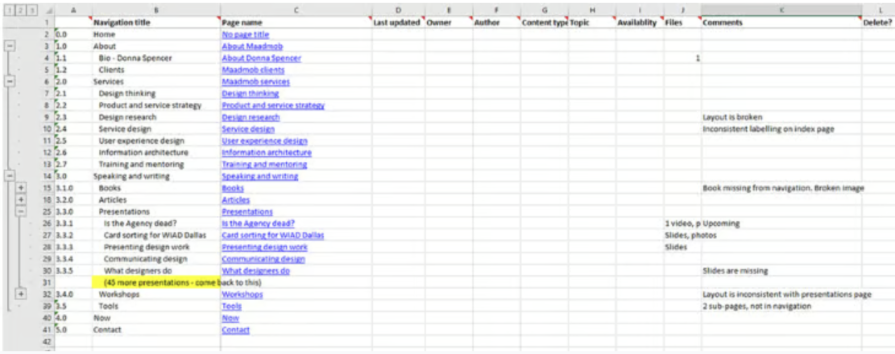

Content inventory

Creating a content inventory is a good exercise to understand what content is available to the user and how to access it.

You usually do that by manually going through the site and mapping every subpage, including:

- Any parent pages

- Owner

- Last time it was updated

- How relevant is it today

- Traffic

This exercise helps you:

- Spot irrelevant content that should be deleted

- Understand the existing hierarchy of information

- Consolidate duplicated content

- Figure out what type of content gets the most traffic and which gets the least

Prototyping and testing techniques

Now that you have an understanding of user behavior and potential solutions, let’s take a look at how to move forward and test if you were right.

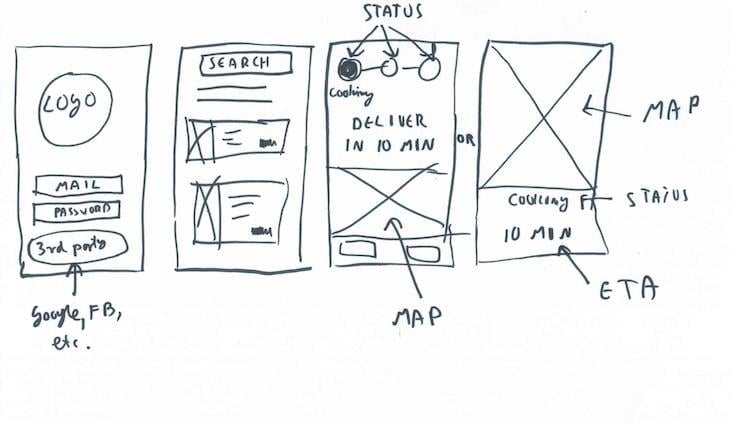

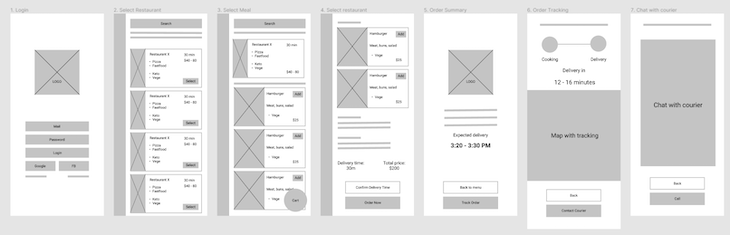

Wireframes

Wireframes are a way to mock up a visual direction before investing in full UI design. Low-fidelity wireframes can be done by practically anyone:

Low-fidelity wireframes help convey the idea:

Medium-fidelity wireframes allow you to evaluate structure and user journey:

High-fidelity wireframes help you to evaluate the high-level look and feel even without a perfect UI.

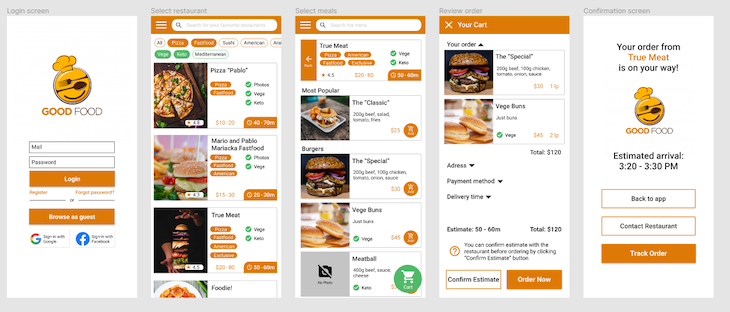

Clickable prototypes

Clickable prototypes allow you to test designs and solutions without any development effort.

Sometimes, a Figma mockup and a few interactions are all you need to gather relevant feedback from the users.

Given how easy it is to turn a wireframe into a prototype, it should be a mandatory step in every design initiative.

A/B testing

A/B testing, which involves showing different versions of the page to part of the users, is the most scientific testing method you can choose.

It gives a clear picture of which design and UX work better from a data perspective and can give you a somewhat precise understanding of the lift (e.g., is it a one percent improvement or a ten percent improvement).

However, it’s also the most expensive method, as it requires developing variants and setting up an experiment, so only use it for confirming pre-validated solutions.

Usability testing

Testing directly with users is a great way to get additional insights if they understand the current implementation and how it could be improved.

In most cases, you simply give the user access to a prototype or working product, ask them to perform a few tasks, and observe how easy the process is.

It can be done in two ways:

- Moderated — With you talking to users directly and observing them as they interact with the prototype

- Unmoderated — Done at scale, when users are recorded but there’s no direct interaction or opportunity to ask follow-up questions

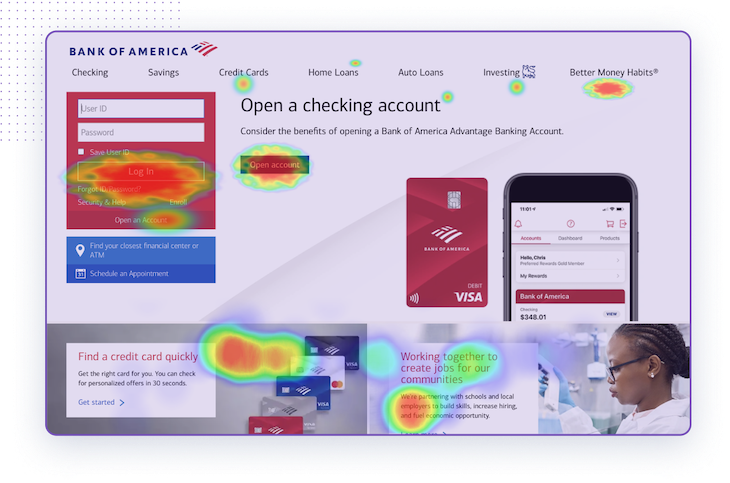

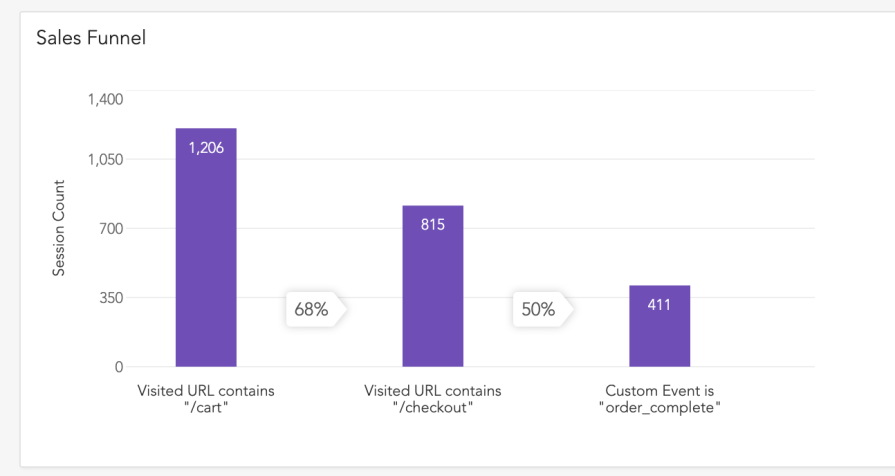

Analytics

Qualitative data helps you notice patterns at a scale, even without talking to users themselves.

For example, heatmaps show you where users spend most of the time and what they click, making it clear how they navigate through the site:

Funnels, on the other hand, can show you at which step most users tend to drop off, making it easier to prioritize next improvements:

There are many more use cases for data analytics, although from experience, UX designers tend to work mainly on heatmaps and funnels.

Final thoughts

UX design is such a broad term that it’s easy to get overwhelmed and confused.

An easy way to manage it is to break down the practice into specific steps and techniques. You can then focus on improving particular techniques to improve your craft, as well as experiment with different techniques to iterate on your design process.

Start with user research, by:

- Conducting user interviews

- Running customer surveys

- Doing field studies

- Exploring diary studies

Then move to analyzing the results and ideating solutions with:

- Personas

- Empathy maps

- User journeys

- Storyboard

- Jobs to be done

- Affinity diagramming

Ensure the architecture of the design is clear with:

- Card sorting

- Site mapping

- Tree testing

- Content inventory management

Lastly, prototype and test solutions with:

- Wireframes

- Clickable prototypes

- A/B testing

- Usability testing

- Data analysis

Voila, we basically went through the whole user experience design process. You don’t need to employ all techniques every single time. It’s more of a library of tools you can learn and use. Experiment with different toolsets for different needs and explore a new approach every now and then.

The post A complete guide to UX design techniques appeared first on LogRocket Blog.

This post first appeared on Read More