AI won’t kill UX — we will

AI won’t kill UX — we will

It’s time we stopped blaming the tools and started asking better questions about how we work, what we value, and how we make space for innovation again.

I was, not all that long ago, convinced my job was safe from the grasp of AI. And while I still largely believe this to be true, the worrying rate at which people rush to adopt AI solutions has cast doubt in my mind. I can’t blame them; AI solutions are fast, consistent, and, on the surface, generally quite appealing. I am happy to adopt AI into my process (I already have), but what I’m not sold on is the idea that AI belongs at the centre of the creative process. It can’t create; it can only replicate – a number of experiments led by MIT highlight how generative AI relies on patterns rather than novel thought. And while that replication is getting eerily good, it still relies on what’s already been done. It’s this part that gets overlooked; the world just sees a quick, acceptable solution, and that’s the part that worries me.

We’ve spent decades in UX preaching the importance of empathy, co-creation, and understanding users as individuals. Yet in practice, these principles still clash with tight timelines and narrow definitions of “usable.” As Adyanth Natarajan puts it, accessibility failures reflect a UX industry still largely built for a narrow slice of the population. Similarly, Andrew Tipp argues that while inclusive design is essential, budget and time pressures routinely undermine it.

Despite valiant efforts to highlight how beneficial inclusive design can be if done properly, these areas remain significantly underrepresented in the development process. The industry is all about time and money; it simply cannot afford the indulgence of real UX design when a cheap and dirty solution is available. AI affords that type of solution. But the more we hand over design tasks to systems that learn from aggregated data and historical patterns, the more we risk standardising everything. If we haven’t got the key right now, surrendering creative processes to AI systems isn’t going to magically unlock it. That dream of inclusive design becoming a benchmark standard becomes even more of a distant fantasy. So sure, we get efficiency, but at what cost?

Although the focus of this article is on the use of AI in removing creativity from the design process, we do have to acknowledge that this argument itself is not new. Voices like Alterio, Seo, and Hurst have all addressed the stifling of creativity in UX/UI, without the involvement of AI.

How much of what we call “design” today can we actually say is original?

Cards on the table: most of us work within fairly tight constraints. Much of the creative intent has been stripped from the process thanks to accessibility guidelines, design systems, asset libraries and community Figma files. All we are doing is joining dots — and that’s essentially all the AI solutions are doing. They pull from these same resources and join the dots based on all the same design system and accessibility rules. So is it really a bad thing?

For me, the answer depends on two things. First, are the people using these tools actually trained to understand how they work? Do they know how to craft prompts that mitigate bias rather than amplify it? Do those employing the people who do this even actually care if not? And second, is the time we save actually being reinvested into exploratory thinking? Into research, experimentation, and future-facing ideas?

If it is, great, but if not, we risk trading away our creative agency for the illusion of progress. That’s not a trade any true designer should be willing to make. If we’re going to hand over all this time-consuming, tedious, dot-joining work to a machine, what better use can our brains be put to?

AI as a replicator, not an originator

Let’s be honest: AI isn’t creative. Not really. It’s a very convincing mimic. It’s trained on what’s already been built, published, and approved. That means it’s built on the ideas that have already won, and those aren’t always the best ideas, just the most palatable or the most visible.

It’s not just design patterns and colour palettes it recycles either. It’s biases. Norms. Cultural assumptions. And if the dataset’s skewed, the output will be too. We’ve seen this in studies like Buolamwini and Gebru’s 2018 Gender Shades, where commercial AI tools misgendered darker-skinned women with error rates as high as 34.7%. Research like this reveals that commercial AI systems, which use datasets collected from the internet and corporate sources, often replicate and amplify existing societal biases.

We’ve built these systems with the same flawed scaffolding we’ve spent decades trying to dismantle, and even with us actively trying to correct these misrepresentations, it may be too late.

Molly Wright Steenson puts it another way:

This underscores a core challenge in generative AI: that we’re building tomorrow’s tools with yesterday’s assumptions.

People are finding all sorts of creative ways to present AI solutions that make us think they’ll make our lives easier, but really, they’re selling sand in the desert. The so-called innovation we’re sold is just feedback looping at scale (Yes, I am a woman obsessed with feedback loops). We taught it, now we’re letting it teach us and itself from the same material.

Now, replication has its place. I’m not saying every login form or onboarding flow needs to be revolutionary. Some of the best design work is invisible. I mentioned earlier that we join the dots. However, we join those dots consciously and with care and concern (or at least we should). If AI becomes the default designer for those parts of the process, we’ve got to ask: where does that leave us? What exactly are we contributing? How do we evolve the craft if we’ve outsourced the groundwork entirely?

The irony is that design should be one of the fields most resistant to this kind of erosion. We’ve spent years fighting for a seat at the table, proving that good design can shape outcomes, shift behaviours, and genuinely improve quality of life. Now that we’ve finally earned our place, we’re being asked to hand the work off to tools that were never invited to the conversation in the first place. Tools that, frankly, don’t care about context, only patterns.

And worse still, the consensus from those who are not willing to, or don’t feel compelled to, look deeper, is that the AI’s output is the objective truth. AI is the oracle. It’s not magic, it’s a system trained on generalised culture. And if we’re not careful, we’re going to automate ourselves into creative oblivion.

Dancing in the dark

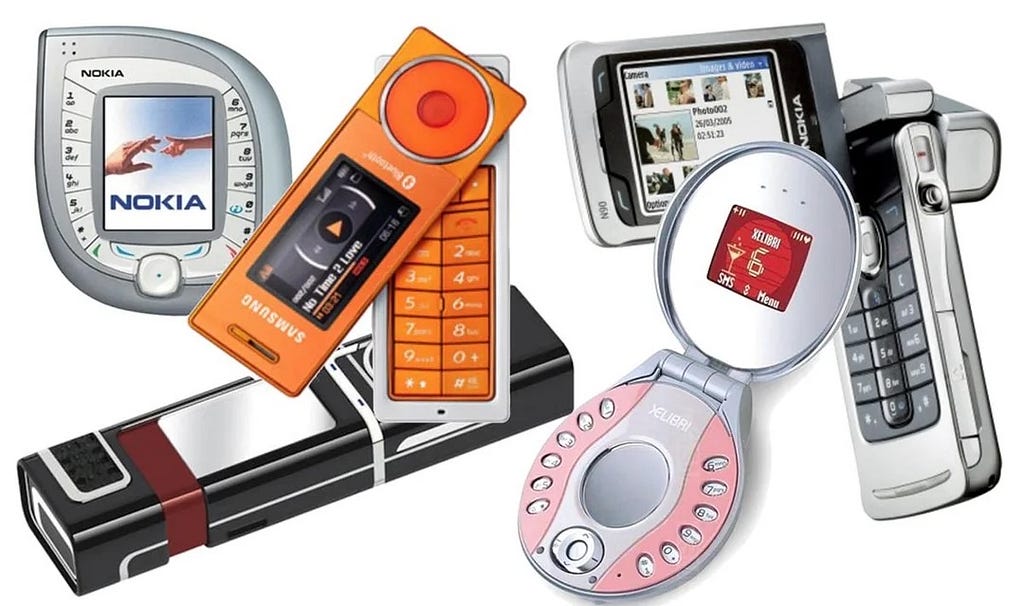

That said, maybe we’ve been stuck in creative oblivion for years. I fondly remember the madness of the mid-90s to early 2000s tech scene. Innovation was everywhere, nobody knew what they were doing, they just wanted to try cool stuff. Candybar phones anyone? Nintendo’s controller design? It was mad. It was fantastic.

I think about 80% of them failed. But it was the best kind of failure. Eventually, the crazy ideas gave way to standards, as they always do; it was Apple or Android, PlayStation or Xbox, Mac or Windows.

And somewhere in all that convergence, UX found its footing. As tech matured, so did our expectations. Weird was no longer wonderful; it was confusing. Unpredictable interfaces were no longer brave; they were broken. UX emerged as a way of bringing order to the chaos, and the goal suddenly wasn’t about standing out; it was about smoothing the friction and making the experience seem natural.

It absolutely needed to happen. Good UX made all this new technology usable beyond the enthusiasts and early adopters. UX standards brought consistency, best practices, and templates built on proven success. But in the search for consistency and usability, we lost something. We stopped asking “What if?” and started asking “What’s the benchmark?”.

Designers and developers, tell me you don’t use Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines or Material Design as your go-to reference points? I’d question the honesty of anyone who did.

When was the last time you radically changed the interaction expectations of a common UI element? What’s popular works, why reinvent the wheel, right? Just like we’ve learned how to open doors and operate hobs through design and exposure (wink wink Don Norman), we’ve learned how to operate a drop-down menu. It’s the evolution of affordance.

So, tell me, when we talk of AI flattening creativity in UX and UI — is it really? It’s not doing anything we haven’t been doing for years. It’s referencing the same libraries and standards, using what we’ve collectively agreed works. What we’re saying we’ve lost is something we gave up a long time ago.

The balancing act

Let’s be clear. AI isn’t the enemy. Complacency is.

I’ve had some good experiences with some AI tools over the last week or so, and I’m confident it’s a fantastic aid. But we’ve got to challenge it. Call it on its bull. Just ask my ChatGPT how many times I tell it it’s wrong…

If we want AI to enhance our work rather than replace the heart of it, we’ve got to be intentional, we’ve got to be aware of what we’re doing. Shneiderman’s Prometheus Principles make this clear: high automation can support creativity and oversight, if we build it that way.

For me, success will hinge on three things: education, integration and balance.

We need to educate ourselves and our peers on what AI actually means, how it functions, and where its boundaries should be in the day-to-day flow of work. This isn’t a process that should be siloed.

It’s not just a developer’s problem or a UX designer’s problem. We need cross-functional AI literacy, encompassing marketing, UX, development, and QA; we should all be learning together. We should all be actively aware of limitations, setting clear prompts, scrutinising outputs, and spotting potential bias before it reaches a user. If we’re going to build products responsibly, we need shared language and a shared level of accountability.

Once we know what AI can and should do for us, the next step is integration. Not just technically, but culturally and ethically. It’s not enough to pick a tool and plug it into the workflow. We need to write documentation: what tools are allowed, how to use them effectively, which stages of the pipeline they belong to, and when it’s appropriate to revert to a little manual thinking. This documentation shouldn’t be top-down; it should be built up collaboratively by everyone who touches the work. We need to establish clear boundaries with shared ownership, giving us the confidence to speak up and use our initiative against AI when we feel it’s appropriate.

That’s the key; we can’t be mindless about AI. Every use should be intentional, and every solution questioned. AI can aid, but the final say must still come from us.

Which brings us to the goal. If the goal is to improve productivity and efficiency by handing over certain tasks to AI models, we have to think about where we’re re-investing this saving.

One way to do this, while also breathing life back into UX/UI and breaking free from stagnant design patterns, is to reinvest in R&D, divergent thinking, and boundary-pushing ideas. With AI handling the tedious stuff, we gain space to explore the experimental concepts that budgets and time don’t usually allow for. It’s in this space that innovation lives. Without it, we risk slipping into an endless loop of safe, soulless outputs. We must be seen to be evolving, adapting, expanding, and keeping our creative ecosystem fresh, not just for our users but in order to feed our AI models with the kind of solutions and thinking we actually want them to reflect.

Final thoughts

Even without automation, we’ve been stuck in a loop of cookie-cutter convenience for years. AI isn’t the reason UX/UI feels stale; it’s the result of it. It merely highlighted the flaws of what was already there. So, rather than worry about AI flattening UX/UI creativity, maybe we should be asking ourselves why it was so flat to begin with?

As designers, we should be looking at ways in which we can utilise AI to support our work. It’s not the designer, it’s the tool, just as Figma and XD were before it. Ben Shneiderman rightly highlights in Human-Centered AI, the goal isn’t to replace us, but to “augment, amplify, empower, and enhance” human potential. The design and creativity still lie with us, should we choose to challenge the templates. Our value shouldn’t lie in speed. It should lie in better, human-centred, experience-driven thinking — things AI can’t grasp, because no matter how close it gets, it will never be human.

So, if we want to avoid becoming passengers in our own process, let’s ensure we invest just as much in training, ethics, and R&D as we do in tools and integration. AI can support great design, but it’s still our curiosity, our challenge, and our instinct that fuel the fire. All the same things that made this industry exciting in the first place.

AI won’t kill UX — we will was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

This post first appeared on Read More